Catherine Oriley, like many poor women in the 19th century, signed her first marriage certificate with a cross. It was 1845 and her family had just landed in London. Her home, Ireland, was being ravaged by a famine that would kill over one million people and force another four million to migrate across the world. Catherine is my great great great grandmother. It was because of her forced migration to London, and then to Australia in July 1852 on the Lady Macdonald that I was born so many generations later.

Discovering a problematic family history is almost always shocking even though it almost never should be. It has become trendy for white celebrities in the US and UK to look back and feel ‘uncomfortable’ or ‘astonished’ that their family owned slaves or participated in the massacre of First Nations people.

In the opening of his book Killing For Country, journalist David Marr traces his family’s participation in the state ordered murder of Indigenous Australians in Queensland and has a similar reaction:

“I was appalled and curious. I have been writing about the politics of race all my career. I know what side I’m on. Yet that afternoon I found in the lower branches of my family tree Sub-Inspector Reginald Uhr, a professional killer of [Aboriginal people].”

An honest reflection and acknowledgement of the crimes of the past at a family level as well as a national one is essential for truth telling or any form of reconciliation. Looking at history at the familial level lays bare how much you benefit from their actions even if you are not responsible for them.

More importantly, it allows you to historicise actions that are seemingly unthinkable. Looking at colonisation, migration, and state building from the lens of individuals forces us to confront the reality that people are trapped by structures and times they cannot control. Work in the style of Marr is important but often missing in the grand attempts to search for seminal moments are the people who fall through the cracks just trying to survive.

Catherine is one of those stories. Born in Dublin in 1827 to a family of coachmakers, she arrived in Melbourne with her husband Henry and three kids James, Joseph, and Mary. Henry worked as a labourer in the London sewers carting excrement. The children were all born in a three-year span and barely survived the voyage. The government sponsored the family alongside 200 other migrants, likely as an attempt to curb overpopulation and poverty in London.

Advertisements calling for workers to move to the goldfields of Victoria and headlines in London newspapers highlighting regular people getting rich encouraged thousands of people to take the perilous voyage.

Rather than finding gold, Catherine lost most of her family in the first two years of living in Australia. James died in 1852 and Henry was killed in a work accident in 1854. Joseph followed a few weeks later. More than a third of children in Australia never made it to age five. Catherine, left with no other option, was forced into a marriage with her boss Samuel Preston, a violent Tasmanian ex-convict who took her to the goldfields.

The goldfields were violent and dangerous. Families lived in makeshift tents that did little to shelter people from the extreme heat in summer and cold in winter. Miners largely acted independently, and there were no labour laws or safety standards. Children regularly died falling down one of the hundreds of mine shafts and fights brought on by a toxic culture of alcoholism and competition, claimed others. Besides small tents set up by the church, there was no formal schooling.

The land itself was being annihilated in a futile attempt to find a couple specs of gold. Samuel never did and went missing under suspicious circumstances, leaving Catherine widowed with children for a second time.

Her true experiences were never passed down. It was believed that Henry was a successful clerk and the second marriage to Preston was wiped from memory altogether.

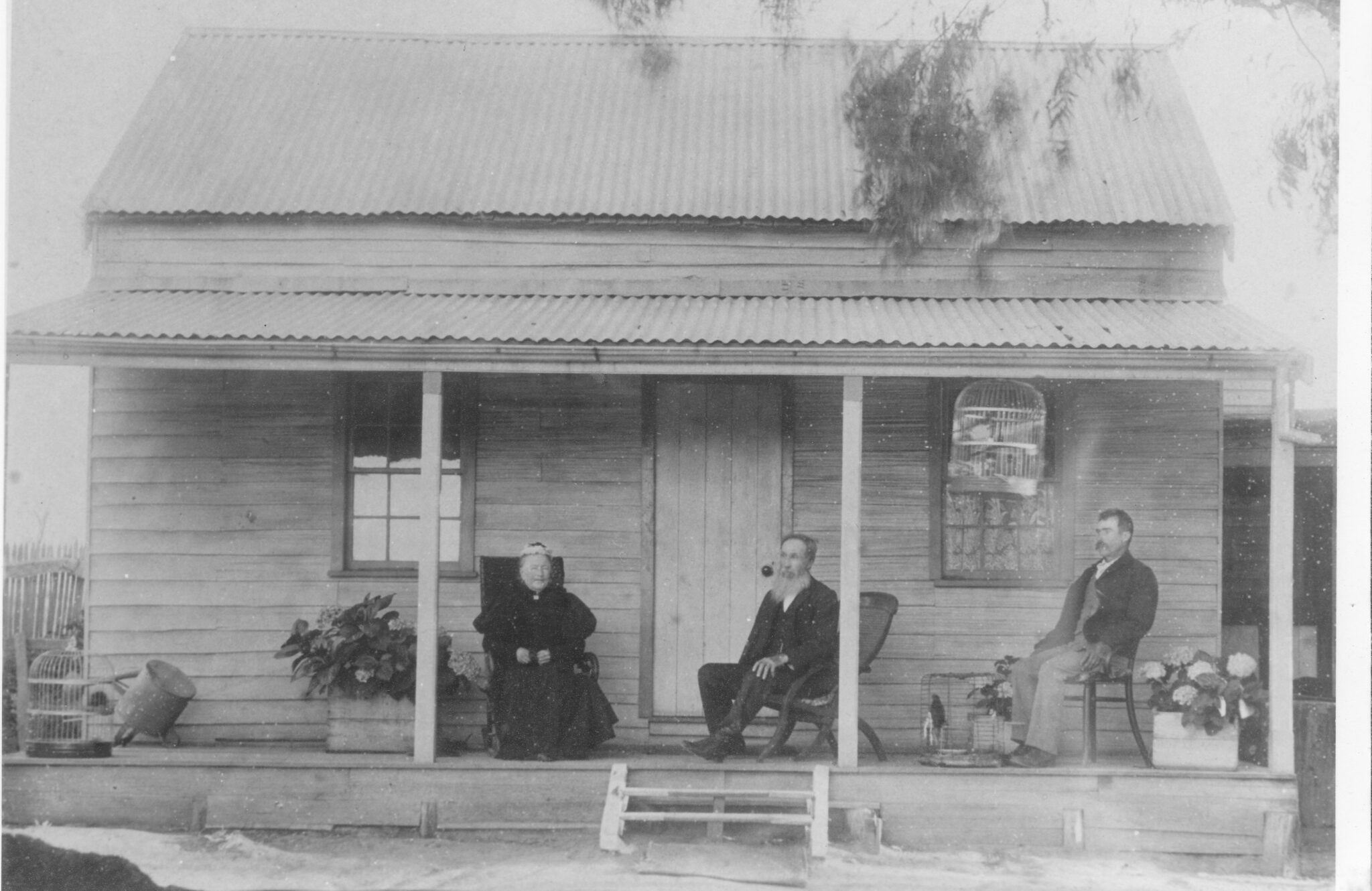

Her third marriage to William Cummins finally brought her life some stability. Cummins came from a family of seamen and dock workers and arrived in Melbourne in 1852, also seeking gold. He and Catherine eventually gave up on finding a fortune, settling instead for a small plot of land to farm. On a cart, they piled their entire lives and finally left the goldfields for Yea in 1870.

In a letter to Geoff and Ninette Dutton in 1973, Patrick White, in his characteristically condescending way, drew on the chaos of the 19th century to define Australian nationality. “What is so amazing is that Australians have changed so little; we are the same arrogant plutocrats, larrikins, and Irish rabble as we were then.”

Some, like White, look down on early Australian migrants for their lack of culture and civility. Others lionize their ‘pioneering’ achievements in a way that ignores their complicity in colonization and genocide. Many just don’t want to know. Marr wrote that his “blindness was so Australian,” because he read book after book on the frontier wars never once asking himself whether his family was involved.

Catherine outlived William by nine years, dying in 1908 aged 71. The very little we can gather from marriage certificates, census listings, and obituaries does not depict a pioneer or Irish rabble but a woman who lived a harsh life in a harsh world. We will never know what she thought of the nation being built around her, but like most people in history, she did not have the luxury of making assessments.