When I’m meeting someone my age, and we happen to have similar political interests, I will almost always ask them if they are a member of their union. The responses I usually receive range somewhere between ‘no, I haven’t really thought about it’ to ‘I wouldn’t even know what my Union is’ or, ‘what is a Union?’

Young people – in particular Gen Z, but millennials too – are not only becoming more and more progressive as individuals, but they are also becoming more politically aware.. While niche university student activism may not be as big as it use to be, students across the board are organising in unprecedented rates to address the major political concerns of their time; things like climate change, a worsening housing and rental crisis, cost-of-living concerns, skyrocketing student debt, slashed public services like healthcare and education, and a more general crisis of inequality characteristic of the mature neoliberal society in which we now live.

Yet young people are not making the natural connection between their unique political awareness and what is probably the most foundational and integral step in progressive organisation: joining your Union. Organising your workplace is at the centre of building a more just, decent, and progressive society. At the end of the day, there are two types of people: there’s the worker and there’s the boss, and this underlines the structural issues of inequality that we face as young people.

Young people and their politics

A recent study by the Financial Times highlighted a massive shift in intergenerational voting patterns within Western liberal democracies. The study found that millennial voters in the UK and the US were the first generation to not trend conservative as they age. Graphs which indicate voting patterns show the Silent Generation (1928-1945), Baby boomers (1946-1964) and Generation X (1964-1980) all slowly sloping upwards toward the Conservative and Republican parties as they age from 20 to 80 years old. Millennials (1981-1996) however, diverge almost completely from this trend, particularly in the UK where the graph shows voters steeply sloping downwards towards progressive parties .

In Australia, voting patterns reflect a similar shift. Primary votes in the 2022 federal election show support for the Coalition is higher than any other political party/group in every single generation until we get to millennials, where they are outstripped by the ALP alone, while the Greens vote is as big as the Coalition vote. The only other generation where the combined progressive vote is more numerous than the combined conservative vote is Gen X. Even still, this was an election where the Labor Party actually won (from opposition) – a rarity in Australian political history, so we would have to account for a fair amount of swing voters in Gen X.

While the data is not yet in for Gen Z’s voting patterns, one can only assume they will follow if not exceed the progressive trend of the millennials. This is because we don’t have to solely measure young people’s politics based on their vote, but also based on their actions. The 2019 climate strikes were symbolic of a massive shift not only in political persuasion amongst young people (the strikes heavily targeted the Morrison government’s complete failure on climate policy but also criticised the ALP’s position which was still not in line with scientific requirements) but also in their engagement with politics. Australians are infamously known for being politically inactive. We stereotypically hate all politicians, think all governments are corrupt, are only motivated to vote to avoid getting a fine in the mail.

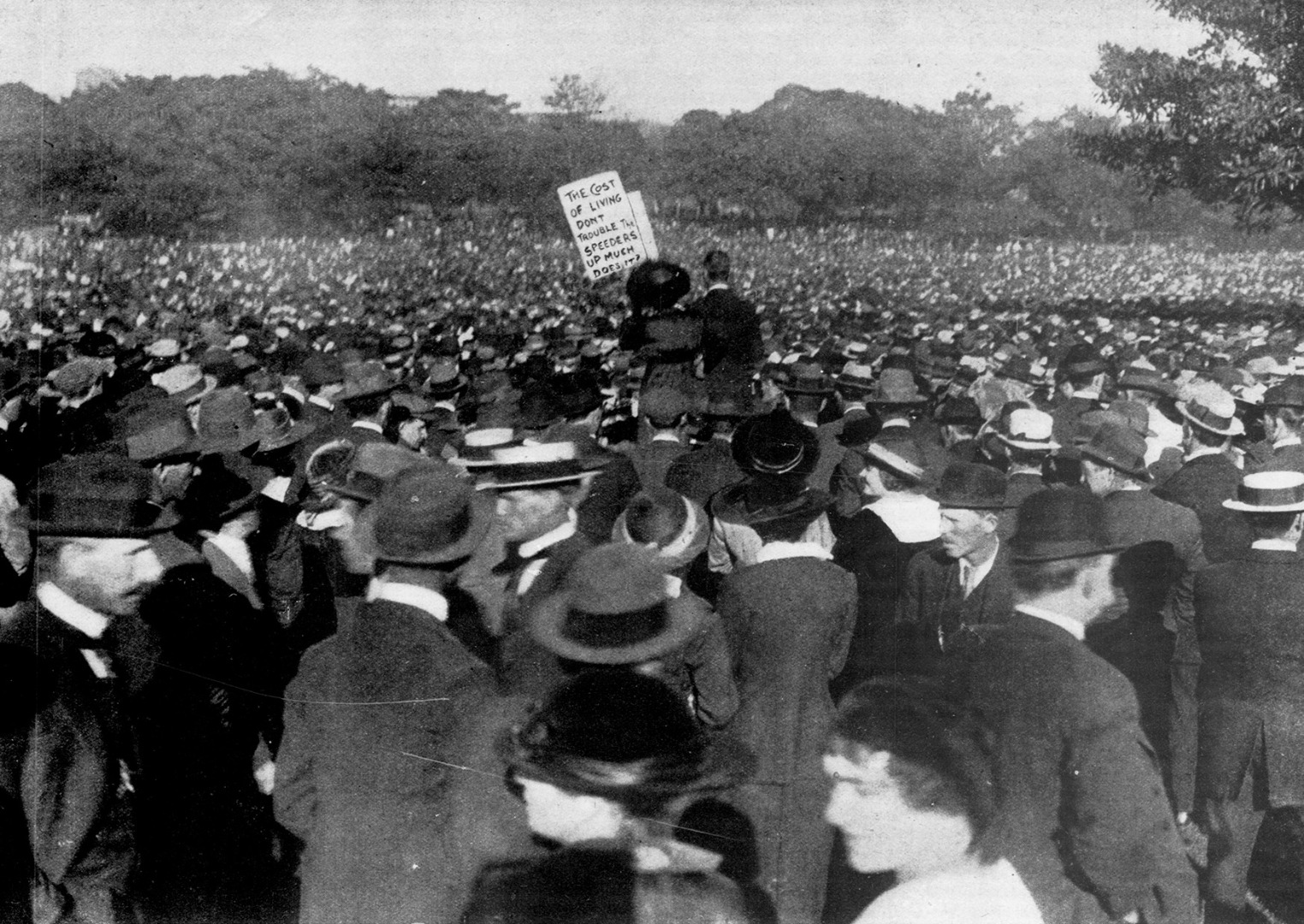

Yet the climate strikers understood that the climate crisis is a consequence of political inaction. Young people certainly blame the inaction of previous generations and are frustrated by a swathe of issues which disproportionately affect them. The ongoing Palestine protests which reflects the largest and most ongoing protest movement we’ve ever seen in this country – only rivalled by those against the Vietnam War – are evidence that we are starting to live in an evermore politically organised society which is mostly mobilised by young people. Young people are not just progressive thinkers or progressive voters – what separates them is that they are progressive actors. This makes it all the more confusing as to why they don’t take that extra step to building power in their workplace.

Young people and their Unions

Trade unions have historically been the epicentre of progressive politics in this country and this is in part due to their relationship with the ALP.

Although the ALP changed significantly over the years in terms of its social ideology, economically it has more so than not reflected the interests of the trade unions – that is, until the 1980s. The Hawke-Keating government sought to introduce neoliberalism to Australia in a unique way. By placating the unions through the promise of social services reform such as Medicare and superannuation, it is posited that they had signed the union movement’s death warrant through the great reduction of trade unions’ power via their control over the labour force. The Prices and Incomes Accord weakened unions’ ability to take industrial action, to bargain for industry-wide conditions and pay rises by introducing Enterprise Bargaining Agreements (EBAs), and paved the way for the Howard government’s all out assault on unions through WorkChoices and ‘freedom of association’ (a framework that empowered bosses to discipline union members and hire scab labour). Notably, neither the Rudd-Gillard nor the Albanese governments have done much to overturn these industrial relations changes.

This has brought us to today where union membership is at an all time low of 13%. Even more depressingly, this is an ageing membership. Statistics show that only 5% of union members are in their early 20s and a measly 2% are aged 15-19. This is a direct result of Government policies aimed at stagnating union growth, furthering a neoliberal agenda which has degraded the solidarity that workers naturally share.

It could be that young people, in particular Gen Z, are nihilistic about their newfound political awareness. While new forms of consuming media (such as social media have allowed, to some extent, a democratisation of engagement with media and socio-political knowledge, they have also had the effect of disillusioning and alienating the public by dumping them with exponentially concerning and depressing socio-political or economic information (i.e., the concept of ‘doomscrolling.’)

This is emblematic of a broader pattern within neoliberalism where capital seeks to capture, co-opt and thus dilute the threat of organised labour. Instead of ever making the jump to direct action, young people are not only nihilistic and disillusioned, but they are caught in a cycle of consumption which is, itself, an engine of capital.

Another reason could be that the majority of young people have simply not developed class consciousness as a distinct form of political awareness – a result perhaps of a focus on superficial or surface-level identity politics rather than meaningfully intersectional leftism? Or perhaps something more structural to the internal machinations of the neoliberal political system.

Former SRC Vice President and incumbent General Secretary Rose Donnelly thinks that structural neoliberal changes to the labour market such as casualisation have diminished workers’ ability to organise due to the nature of their insecure work and that this in turn disproportionately affects younger generations as they enter the labour force: “the overwhelming casualisation of the workforce has meant young people don’t have a reliable paycheck. They subscribe to Netflix, they subscribe to Spotify, but they cannot see the value in joining their union.”

Donnelly argues that the exacerbation of a “dog eat dog mentality in the workplace” by a coalition of bosses and conservative media means there is “a lack of solidarity between young workers, who don’t see the value in a union.”

Whatever the reason is, there is a common link: neoliberalism as an economic system has changed the relationship between capital and labour in such a fundamental way that it is increasingly hard to organise against the underlying common enemy, which is capital. Through a strategy of divide and conquer, neoliberalism has atomised individuals, pit generations against each other, kept activists focussed on sectarian and fragmented causes, and thus has fractured the engine of solidarity – the union movement, the only movement truly capable of unifying the working class, has as a result suffered.

Young people must organise in their workplaces. Industries with low union density are those which are mostly made up of young, unskilled workers who are still going through some form of tertiary education (i.e., hospitality, the arts industry, retail, etc).

Activists have a duty not only to organise against singular threats, but to unify those who are opposed to our neoliberal society – to agitate for people, especially young people, to organise their workplace and join their Union.

At the end of the day, there are two types of people: there’s the worker and there’s the boss; there’s the fossil fuel boss, there’s the weapons manufacturing boss, there’s the boss of the bank, there’s the university boss and so on. Our capitalist system is at the heart of the structural inequality which plagues our neoliberal society – organising against it is the only key to advancing a just, sustainable and equal future for all.