The International Court of Justice orders additional measures

On March 28, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) decided on South Africa’s March 6 request for the indication of “additional provisional measures and/or the modification” of the January 26 order in the South Africa v Israel case regarding the genocide in Gaza. Israel had responded with its observations to South Africa on March 15.

The Court acknowledged that “the catastrophic living conditions of the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip have deteriorated further”, specifically citing the “prolonged and widespread deprivation of food and other basic necessities.” It also acknowledged that “Palestinians in Gaza are no longer facing only a risk of famine…but that famine is setting in”.

The provisional measures have been modified as they did “not fully address the consequences arising from the changes in the situation” and are as follows. The State of Israel must:

- Cooperate with the United Nations (UN) to provide “urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance, including food, water, electricity, fuel, shelter, clothing, hygiene and sanitation requirements, as well as medical supplies and medical care” to Gaza along with “increasing the capacity and number of land crossing points”.

- Ensure that “its military does not commit acts which constitute a violation of any of the rights of the Palestinians in Gaza as a protected group” under the Genocide Convention, including the prevention of humanitarian assistance. The ICJ also called for Israel to “immediately suspend its military operations” and lift “its blockade of Gaza”, noting that air and sea routes cannot be the alternative to land routes.

- Submit a report on these ordered measures within one month.

According to lawyer and research analyst, Naks Bilal, Israel’s previous report to the Court was not made public. While not an unusual outcome for a state’s response, South Africa was “evidently unimpressed”.

Alonso Gurmendi Dunkelberg, lecturer in International Relations at King’s College London, explained that the ICJ is essentially saying that Israel’s “business as usual” amounts to non-compliance and/or a breach with the first order, which led to the increased specificity in wording of this new order. Michael Becker, Associate Professor of Law at Trinity College Dublin, agreed, stating that “Israel’s actions since 26 January”, including the starvation of Palestinians, “have arguably made South Africa’s legal case considerably more compelling.”

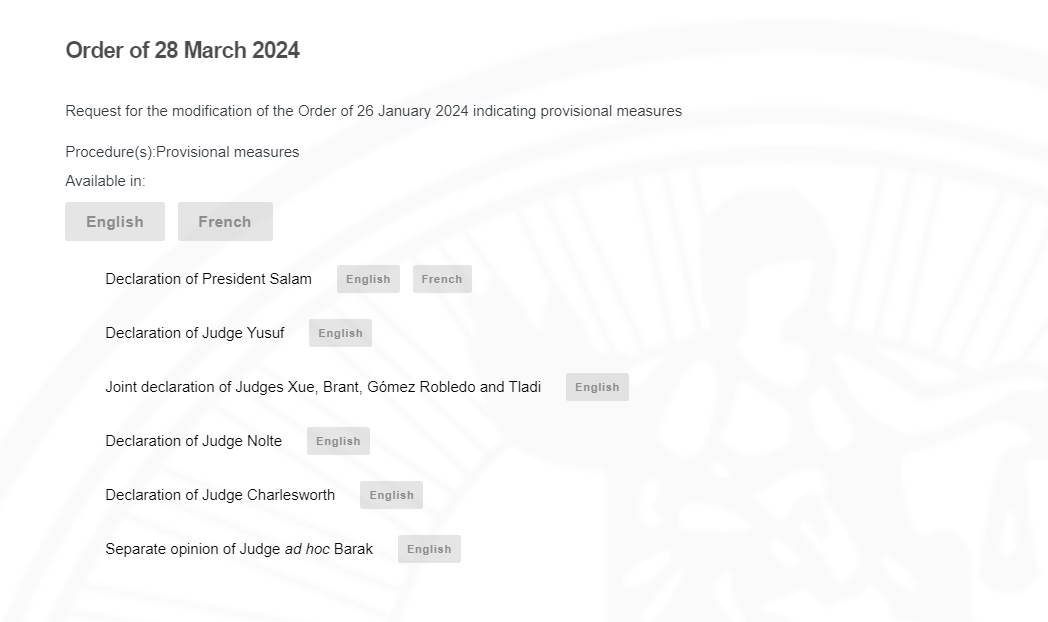

While the ICJ pointed to the UN Security Council Resolution 2728 demanding an immediate ceasefire starting with the period of Ramadan, judges of the ICJ released separate opinions and judgements, indicating an internal divide amongst the Court regarding the wording of the orders. In four single declarations and one joint declaration, seven judges believed that the ICJ should have explicitly ordered Israel to suspend all military operations in Gaza and call for an immediate ceasefire.

In a joint declaration, judges Xue Hanqin (China), Leonardo Nemer Caldeira Brant (Brazil), Juan Manuel Gómez Robledo (Mexico) and Dire Tladi (South Africa) communicated deep “regret that this measure does not directly and explicitly order Israel to suspend its military operations.” However, they commended this order for being an improvement due to it shifting from the request that Israel “enable” to “ensure” the provision of humanitarian aid.

While Judge Nolte (Germany) agreed with the pre-existing order, he hesitated to vote in favour of the new order based on the fact that “this terrible situation would most probably not exist if the Order of 26 January 2024 had been fully implemented.” Instead, Nolte’s statement considers the technical legal issues in the interest of the Court’s best practice while acknowledging the “current horrific situation of the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip” where Israel is using “hunger as a ‘weapon of war’ and the provision of humanitarian aid as a ‘bargaining chip’.”

This is notable because Nolte wasn’t entirely satisfied that South Africa could prove Israel’s actions encompassed genocidal intent, especially considering the ICJ demands proof of the highest standard. In this statement, Nolte is seemingly indicating that “Israel’s starvation of Gaza itself can plausibly constitute a genocide.”

Judge Charlesworth (Australia) argued that the Court should have “made it explicit that Israel is required to suspend its military operations in the Gaza Strip, precisely because this is the only way to ensure that basic services and humanitarian assistance reach the Palestinian population.”

Charlesworth also stated that the Court’s power lies in directing measures at states bound to the ICJ statute, alluding to an inability to compel Hamas, a non-state actor. As such, Charlesworth has requested that the Court indicate its measures to both Israel and South Africa, as they are parties to the case and Genocide Convention.

Judge Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf (Somalia) said in a declaration, “the Court cannot take the position of a powerless bystander in the face of the possible commission of acts which are so offensive to the conscience of humanity” and that “nothing less” than the right of existence of Palestinians in Gaza is at threat.

“The alarm has now been sounded by the Court. All the indicators of genocidal activities are flashing red in Gaza,” Yusuf warned.

President Nawaf Salam (Lebanon) reiterated the first order where the Court referred to an “immediate risk of famine”, and identified that this risk “has now materialised”.

Salam concluded, “we are therefore faced with a situation in which the conditions of existence of the Palestinians in Gaza are such as to bring about the partial or total destruction of that group. It is important to remember that this conclusion is without prejudice to any decision on the merits of the case before the Court.”

In his separate opinion, Judge ad hoc Aharon Barak (Israel) stated his concern that the Court’s “approach to this case is steadily leaving the land of law and entering the land of politics.” Barak focused his critique around the reasoning that “there is no ‘change in the situation’ that justifies the modification of the Order of 26 January.”

Barak also stated that “the war in Gaza is Israel’s second war of independence”, which led Nimer Sultany, reader in Law at SOAS University of London (the School of Oriental and African Studies), to comment “what does it say about Israel when it’s ‘independence’ = ethnic cleansing, genocide. On repeat.”

In an opinion piece, Alonso Gurmendi Dunkelberg remarked the following about the overall case, arguing that Israel’s continued military response and hindering of aid after the ICJ provisional orders is strengthening South Africa’s case:

“At the end of the day, therefore, it looks like Israel’s own conduct has seriously weakened its argument that the existence of (some) humanitarian aid and precautions in attack mean it has no genocidal intent. Instead, it seems, by its own actions, it has lent credence to South Africa’s argument that these humanitarian policies are part of the genocide and demonstrate, rather than disprove, Israel’s genocidal intent.”

Ireland to intervene

Micheál Martin, foreign minister of Ireland, announced that it will apply to intervene in the case of South Africa v Israel, stating that it will seek to widen the definition of genocide to include blocking humanitarian aid. However, Ireland will formally file its application “after South Africa has filed its memorial to the court, which could take several months”.

Palestine to intervene

The State of Palestine has declared its intent to intervene in the case of South Africa v Israel, and is asking other states party to the Genocide Convention to do the same.

Legal scholar Maryam Jamshidi argued that Palestine should have a say in a matter concerning Palestinians, but also recognised that it would complicate the case legally given that the Court is only open to states. Palestine’s quest for statehood has long seen debate over the statehood criteria under the Montevideo Convention (1933): a permanent population, a defined territory, a government, and the capacity to conduct international relations. Notably, this convention does not provide legally binding precedent; rather, it reflects custom and state opinion on the pathway to statehood.

On April 2, the State of Palestine followed up this move by applying for full membership status at the United Nations, specifically asking for the application to be given to the Security Council. Palestine previously applied in 2011, and has been a non-member observer state since.

Update as of April 6: The Republic of Colombia has announced it will also intervene, “claiming that [South Africa’s] case against Israel’s violation of the Genocide Convention is compelling.” Unlike Nicaragua which previously sought to intervene under Article 62 of the ICJ Statute —showing legal interest in the case — Colombia has invoked Article 63, citing its responsibility as a state party to the Convention.

The ICJ case remains ongoing, and Honi Soit will follow any updates.