Queer communities have a long history of carving out private spaces for social and sexual interaction, utilising urban geographies to resist oppression and build a sense of belonging.

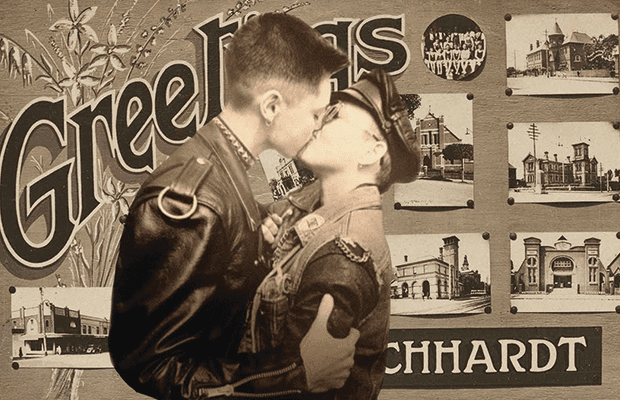

In Sydney, these gay neighbourhoods can be found around Oxford St and Newtown, and remain integral to many queer identities. However, Sydney was also home to a third, often forgotten gay village that catered specifically to queer women; affectionately nicknamed “Dykehardt”.

Occupying urban space in such a manner has historically been particularly difficult for queer women. In order to explore their queer identities, individuals were often required to leave marriages. This frequently left men in a more financially autonomous position, thus allowing them greater financial freedom in placemaking. Women have further been obstructed from entering queer circles by both laws and social norms, which prevented them from entering the “camp” bars established on Oxford St during the 1950s.

Nonetheless, as the number of queer venues grew and social attitudes began to relax, queer women began to similarly lay their roots in Sydney’s inner city. The establishment of lesbian bars such as Chez Ivy and Ruby Red’s were paramount in this development, acting as social spaces which helped facilitate the networking and the development of new lesbian identities. Nonetheless, in the 1970’s as gentrification began to take hold, queer women found themselves gradually priced out of the primary gay village of Darlinghurst. This prompted a migration of queer women to the more affordable inner west suburb of Leichhardt.

In the following years, Leichhardt became an integral landmark of Sydney’s lesbian scene. The development of community organisations and services such as Bluetounges (a lesbian writer’s group), Clover Businesswomen’s Club, Lesbian Line Counselling, the Leichhardt Women’s Health Centre and regular lesbian nights at the Leichhardt Hotel helped foster a strong sense of community and further attract queer women to the area. Establishments such as the Feminist Bookshop, located in the neighbouring suburb of Lilyfield, were particularly key in maintaining community links, the bookstore acting as an important point of political and cultural reference for newcomers.

Residents of this “lesbian haven”, as documented by the Leichhardt Library Oral History Project, reflect affectionately on their time there. Teresa Savage and her longtime partner Louise moved from London to Leichhardt without any initial friends in the community. However, she quickly felt a close sense of belonging, joining the Bluetounges and the lesbian choir, and starting her own lesbian mothers group. She described a positive experience as a Lesbian mother at Leichhardt Public School and found that the principal and teachers were broadly positive and inclusive. However, despite the relative social security provided by Leichhardt and the surrounding areas, it is important to note that homosexuality still resided far outside of the social norms of the 70s and 80s. Consequently, despite the relative security offered, many suffered persistent harassment from neighbours.

By the end of the 1990s, this uniquely lesbian village began to dissipate. Sweeping gentrification by a new, university-educated middle class increased house prices and rents such that queer women and other low-income groups were forced to move elsewhere. Simultaneously, the lesbian community itself began to fracture, as discourse heated up over the inclusion of trans women within this label. As a result, whilst queer women migrated to other areas in Sydney’s inner west such as Newtown, Marrickville, Enmore and Erskineville, a centralised heartland similar to the likes of Dykehardt has failed be established.

Without a centralised community to provide a reliable economic base, and lacking the material means shared by gay men, lesbian establishments such as bars and bookstores are similarly in decline. The Feminist Bookshop has long closed its doors, and despite whole streets of gay male clubs in Sydney, a single lesbian one now ceases to exist beyond one night a week.

Consequently, queer women instead occupy social spaces through alternative networks, seeking community in liminal areas outside the bounds of heterosexual norms. This reflects the historical tradition of lesbian existence as a quasi-underground reality, facilitated through groups and collectives rather than physical forums. Today, many of these “floating spaces” are not even advertised, created by private attendees for friends or family. Furthermore, as society shifts towards a fluid conception of queerness, whereby gender and sexuality are a spectrum, new queer spaces are emerging which cater to and celebrate all kinds of identities.

Although now no longer a gay village, Dykehart’s legacy lives on through the various institutions it brought about. This reflects how queer spaces are in an inherent state of perpetual change, moving through a heteronormative world on a search for safety. The now lost neighbourhood of Dykehardt reflects this process, illustrating how like all neighbourhoods, gay neighbourhoods are challenged by gentrification and shifting social values.