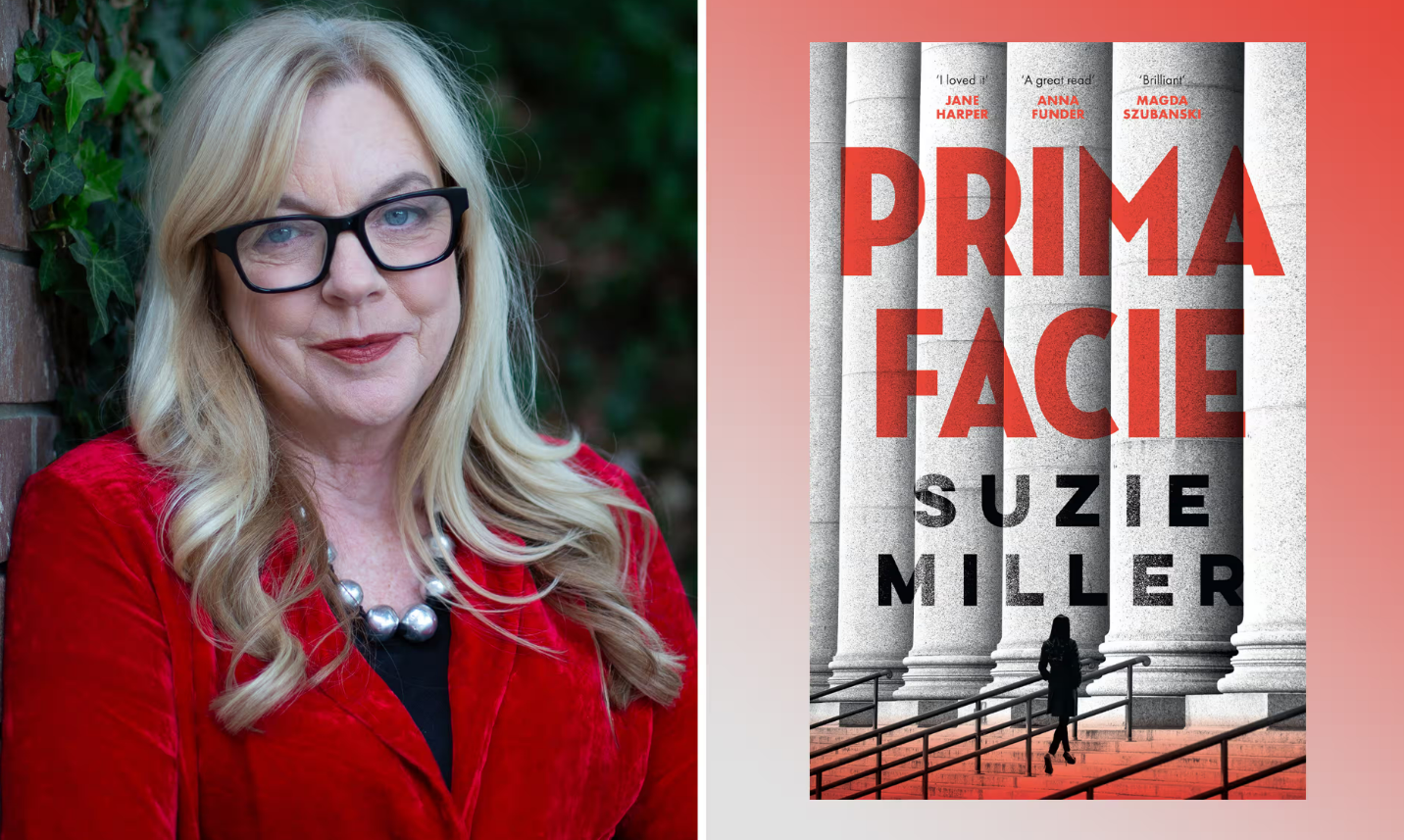

Suzie Miller is a playwright, screenwriter, and novelist known for her smash-hit one-woman play Prima Facie, which ran a sold-out, critically successful season on London’s West End, followed by a critically successful season on Broadway. Miller practised human rights law before turning to writing full-time and is currently developing theatre, film, and television projects across the UK, US, and Australia. Prima Facie (2023) is her first novel.

I spoke to Suzie after she landed in Sydney from the Women of the World (WOW) Festival in Greece and addressed her jetlag with a coffee from Bangkok Bowl and Brew House.

TW: discussion of sexual assault and rape.

Valerie Chidiac: You grew up in Melbourne, and now live between London and Sydney. Which place has had the greatest influence on Suzie, the individual, as well as Suzie the writer?

Suzie Miller: Susie, the individual… probably in Australia because I had to learn lots of ways of being just in order to survive. And Susie, the writer, probably London because that’s where I’ve had my greatest successes, and where I feel there’s a lot of scope for my work there.

VC: Which place would you say has the worst weather?

SM: Look in all my life, I’d say London. But I have to say, with the very high humidity in Sydney earlier this year, when I got to London I was quite relieved to have some cool air. But Australia’s got much better weather, a bigger sky and the scope to plan outdoor activities more often.

VC: You’ve done it all; studying immunology and microbiology plus law. I know it can be weird quoting you to you, so I’m going to quote your cousin Jenny who said, “Suzie is the over-achiever in our family, always having 10 ideas before breakfast.” From one overachiever to another, would you describe yourself that way, and is ‘overachiever’ obscured by a negative light?

SM: The concept of being a high achiever is laden with issues. What people don’t realise is that if you strive quite hard and achieve, sometimes you run the risk of being torn down by that tall poppy syndrome that is really rife in Australia. Anyone who’s an artist will tell you that there’s a vulnerability underneath their voice, and that their storytelling comes from a place of struggle. In some regards, you’ve had to work through lots of issues in your own life and also in your own storytelling capacity. As a female writer in theatre, it’s been tough and it’s only more recently has it been something celebrated in Australia. It still is tough, but it was completely impossible when I first started out. I didn’t come from a family of university-educated people, so I had to find my own way in the world, and develop that grit. It is also demoralising to think that you have more success outside your own country, and often you get a bit of backlash in Australia.

VC: Yes, hopefully that will change sometime soon.

SM: I hope so, because I look at all the young people that I mentor and talk with, and I don’t want them to go through that. I want them to be able to strive to be the best they can possibly be without that fear of backlash. The tall poppy syndrome in Australia is something that we should grow out of. The poppy is just as easily cut down by the world, and the one place that you wanna feel loved is in your own country because they’re the people that you really want to speak to.

VC: As a National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) alumni, do you have a memorable instructor, class, or activity that confirmed your passion for storytelling and motivated you to keep pursuing theatre?

SM: NIDA was really great for me, because I was one of a group of seven people that was selected to be part of the writer studio, and at the time Ken Healey and Francesca Smith were running the course. Francesca Smith became a very close friend of mine, and is an astonishing writer, dramaturg, and director. Her belief in me as someone who had a unique voice gave me the faith to push forward with writing. At the time I felt torn between my commitments to the law, to writing, carving time out of my newborn’s life and fighting for human rights. I had to value what I was doing so that it was worth doing it, and she gave me that value. What was really special for me also was being amongst other people who take theatre seriously. At the time it was all about theatre, it wasn’t about film and television. And there’s something about being embedded in that for a long period of time that makes you see things through the prism of theatre.

VC: Speaking of your work in human rights and as a criminal lawyer. Would you describe the state of human rights in a greater state of disarray than before? Or is this more a symptom of us being able to witness what is going on in institutions, workplaces or countries, no matter where we are?

SM: I think the state of human rights is worse than when I was working in it. It’s always been bad to be honest, even if you have the optimism to work towards a better future. Young people these days are much more aware, and have always been prepared to speak out, gather and demonstrate their feelings. People are also more willing to doubt the media and find out what the media are missing out on. We also struggle with racism in Australia and couldn’t find a way for Aboriginal people to have the Constitution just make a mention of their rights to this country. We don’t have a great reputation overseas for race and gender, and there’s a reason for that. I think that Australia really does need to strip away some of that defensiveness that we have and interrogate: why haven’t we evolved as much as we should in that regard?

VC: Some people still refuse to kind of acknowledge that at all.

SM: The mainstream does refuse to acknowledge that, and there’s certain newspapers that really push that it’s all ‘woke’ politics. We’ve grown up as a nation, and we need to really push through that. There’s no need to be frightened or fearful of scarcity, there’s a lot to go around and a lot for everyone to offer.

VC: Your play, Prima Facie, achieved astronomical levels of success, including in its West End and Broadway runs with Jodie Comer. It was also my highest-rated book of 2023 on Goodreads.

SM: Good for you.

VC: Did you ever see yourself going from playwright to writing a novel version of the play?

SM: It wasn’t unexpected, because when I first wrote the play I had reams of notes, and thousands of pages that I had to cut down to fit a 90 minute show. Prima Facie has now gone on to be translated into 30 languages, with 20 different productions this year in Germany alone. I was so happy to be able to go back and restart the novel version because it had been tested on audiences. I could now recognize what I wanted to sort of delve into, and how I wanted to excavate the emotional experience of the character. The novel has done very well overseas in Britain and America, and is now translated into Hungarian, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch with many more to come. It’s following in the footsteps of the play being translated. Once you write something and put it out there, it doesn’t belong to you anymore. It belongs to the people that read it or interpret it or put it on stage. I’m onto my next stories now, but I’ll always be extremely proud of that particular story.

VC: I had the chance to review Jailbaby at SBW Theatres in its revival. How involved were you in this process?

SM: I was very involved in it and consulted during the developments, and was there for the rehearsals. The great thing about the Griffin Theatre is that it is a writer’s theatre. I’ve been involved in various other organisations because of Jailbaby. The audiences also had really interesting feedback; some preferred it to Prima Facie even though it’s a more intense play. It meant a lot to me to have it play in Sydney, then for it to go on again. It’s looking like it will go on in London next year. My plays have either started in London and come here, or vice versa.

VC: You mentioned work with organisations as a result of Jailbaby. Would you like to speak more about that?

SM: I work with an organisation run by Robert Tickner called the Justice Reform Initiative. I give lectures to judges, barristers and anyone interested in reform. I see myself just starting a conversation, and then people take that conversation to the next level and discuss whether it’s appropriate to talk about reform or not. So far they have. In London, there’s been profound changes to the law as a consequence of Prima Facie. Many judges have to watch the National Theatre (NT) Live version of the play before they’re allowed to sit on sexual assault cases. One judge even changed the direction to the jury for sexual assault and rape cases, and now everyone has to read that out. Having been a lawyer, I never thought I’d have that effect from writing a play, but it’s been the other way around.

VC: I read the [Jailbaby] screenplay afterwards and could hear the actors’ voices in each of the characters. Even though Prima Facie is a one-woman show, did the performances of Sheridan Harbridge or Jodie Comer influence you when adapting Tessa’s story into a novel?

SM: Sheridan and Jodie had quite an impact on me in terms of shaping the character. Sheridan helped me cut down the play to what it should be, as did Lee Lewis, the director in Australia for the main production. But in both the play and in the book, Tessa is not described because she’s every woman. There’s currently 20 different Tessas in Germany, Iceland, all over Scandinavia, Italy, Pakistan, and India. I never wanted to give her a physical description because I wanted people to imagine the Tessa that they wanted to. I don’t have ownership over the story anymore. Now it’s for readers and audiences to respond, take it on board and press it into the hands of other people.

VC: A key moment that has stayed with me and I think about often was when journalist Rachel Myers approaches Tessa and thanks her for her testimony, saying she is “one in three” women who have been sexually assaulted. Both of these characters are in occupations that ideally speak truth to power. Have you had people of similar or different walks of life approach you to speak about moments from the story that made them feel seen?

SM: I’m glad you picked up on that because the end of the novel is different to the play. During the West End opening night, a very glamorous and confident female producer came up to me at a drinks party and said, “I love the play, and want to let you know that I’m one in three”. She didn’t have to explicitly refer to it as a rape. It felt like she was owning that this had happened to her and she was including herself in a chorus of women without saying, ‘I’m a victim’. From then on, I got thousands of letters and cards, or people would come up to me on Broadway or on the train and say, “I saw your play. I just want you to know I’m one in three”. This gentle adoption of the phrase made me realise it should be the end of my novel. I wanted someone who is in a different profession to tell the world what Tess said in court, and then for others to read that and do something. It’s similar to how audiences have brought others to see the play. Rachel [the journalist] is throughout the story, but you never see her until the end when she comes up to talk to Tessa. You think she wants to interview her but what she says is, “I’m telling you that this is me, and I’m going to use my platform to report what you said”. That’s the little secret of the book, it has an ending that offers a passing of the baton between two women in positions of power. And that there’s the possibility of it not being put aside just because Tessa is finished.

VC: What is in the near future for Suzie Miller, both in the Australian theatre scene and internationally? I know the pre-production process is very complex and you may not be able to say much, but are there any updates on the Prima Facie film adaptation, directed by Susanna White and starring Cynthia Erivo?

SM: I’m thinking about my next novel now, and whether it comes from the idea of a play, or from something completely separate. As for Prima Facie, it’s part of a trilogy. The second story is about showing what happens when a young man is accused of sexual assault, and how how we raise our boys, and how at around 16, something changes, and they get other influences that teach them to not respect women. The third part of the trilogy is talking about what women want out of the response to sexual assault, whether that be an apology, an acknowledgement that they are not disbelieved or going to court so the perpetrator can go to jail. All are legitimate responses, and I feel that women aren’t always given the choice of how they want to resolve the issue. One of those two plays is going on at the National Theatre next year. RBG: Of Many, One is being rewritten for New York and I’ve also got another play set in Ireland that’s going to London next year. In terms of film and television, a lot is happening. The Prima Facie film is in pre-production at the moment and we’re looking at filming it later this year after being put off by the SAG-AFTRA strike. Obviously, Cynthia [Erivo] is quite in demand at the moment, because she’s in the Wicked films, but hopefully filming will fit around her Wicked commitments.

VC: And for the final and most important question, have you seen the photo of Jacob Elordi at Sydney Airport buying Prima Facie?

SM: Everybody sent it to me. I didn’t know who Jacob Elordi was then. I kept calling him Jason Elordi. I didn’t realise he’s Australian too, which was great. If men are buying and reading this book, there’s the possibility of some really good men being around. In the first preview of Prima Facie in Australia there was a group of 14-year-old boys from a private school with their drama teacher and they all loved the play. They stood up to get our autographs outside, and they were talking about it. One of them said to me, “I didn’t even know that was rape”, and I thought therein lies the problem. And yes, he is a naive young 14-year-old, but he didn’t know, neither did any of them. When someone like Jacob Elordi shows the template for what it means to be a sensitive, thoughtful man, it could help many to read more about it and educate themselves. It’s funny you picked up on [Elordi] because while writing the second play of the trilogy on what happens to boys when they disappear into the ‘bro zone’, I’m hoping it is an invitation to men, to football coaches, to big brothers, to interrogate that ‘bro zone’ and say that this casual misogyny is not okay. So if Jacob Elordi picks up the book and shows that he’s prepared to engage in it, why can’t all men — popular or not — do the same?

VC: And it speaks to your earlier point about role models and how it shouldn’t just be women who adopt that burden.

SM: Absolutely. Women aren’t doing this to themselves. Men are doing this to women, so they have an obligation. One of the points of my next play is that mothers do the best they can. But then boys end up in ‘boys clubs’ and ‘locker room’ cultures, and what goes on there is very hard for women to reach. Men have to step up and have these conversations with younger boys so that they are not led astray by their peer group.

Suzie Miller will be appearing in two events at the 2024 Sydney Writers Festival, Suzie Miller: On Prima Facie & From Stage to Page. Prima Facie is available across Australian bookstores.