What do students want and how are they going to get it? The media is quick to bury their demands, management at the University of Sydney wants control of the narrative again, and students just want to graduate without blood on their hands. But we cannot forget what this is all for: an end to the genocide in Gaza, and a free Palestine.

Media

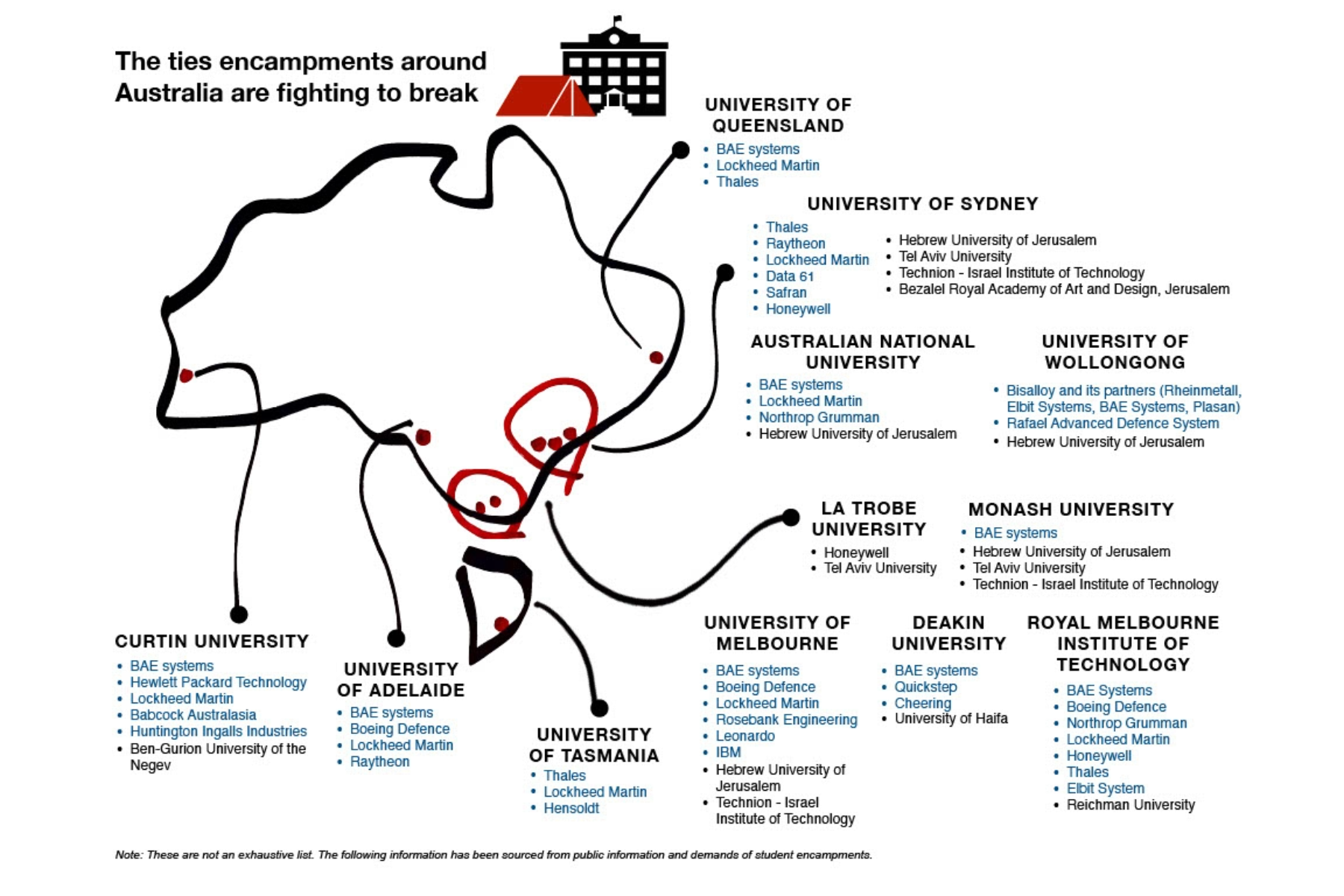

USyd’s encampment demands are simple: the University of Sydney should “cut ties with weapon’s manufacturers and Israeli universities”, and the Minns government should “drop the charges and scrap draconian anti-protest laws.” A statement from eleven Australian university encampments also implores each respective tertiary education institution to “sign on to the international Boycott, Divest & Sanctions [BDS] statement.”

However, encampments have been continuously dismissed, weaponised and demeaned by mainstream media outlets. It is no surprise that right-wing outlets like Sky News have described the encampments as “taking over” Australian universities. These sources characterise protestors as “rowdy”, “heated” and “divisive”, and regularly draw parallels with their US counterparts facing police brutality and repression. Many campers at USyd have told Honi Soit that reporters from the “Murdoch press” have attempted to “make them look bad” by “wedging” or “gotcha” questions. The overwhelming feeling generated by this spin is that the encampments should warrant “growing concern.”

Coverage from centre-left sources like the ABC and The Guardian is not as blatantly corrosive. Rather, they reframe the situation around “the right to protest on university campuses”, “freedom of speech” and “threats to public safety.” Mainstream media only report when there is a request from university management to “disband on-campus encampments”, or when violence occurs at a protest. It takes issue with the actions of protestors, rather than the genocide currently occurring in Gaza. Without explicitly saying it, these pieces condemn student encampments as tolerable, but barely; only because sending police on university campuses would look worse than leaving peaceful protests be.

With the timing of the Budget, the mainstream media have also reported on encampments as a vehicle to analyse federal politics, focusing on politician’s reactions and statements on antisemitism and Islamophobia. Relatedly, the reporters allocated to covering the encampment — including at Nine and Murdoch — work in the Federal politics portfolio, rather than Education. Clearly, media platforms are more curious about politicians’ response to the encampment rather than the encampment’s impacts on students and the education sector.

Consequently, national and transnational student media organisations have become bastions of protest coverage, personal testimonies and daily updates simply by reporting on encampment events when no other news outlets can or will. Unofficial forums for student discussions, such as USyd Rants, disproportionately platform anti-encampment sentiments and ridicule. Student newspapers form the main source of student-centric, accurate information on the encampments.

Honi’s reporting techniques for this event are novel, but not new, and requires altering to our approach. Most mornings, one of our editors visits the encampment and posts a schedule of the day’s events on our Instagram page. In the evenings, we complete a write-up of the teach-ins, rallies and organising meetings which occurred. However, the stream of information and content emanating from the camp is constant; at no point in recent memory has student media covered a movement of this scale, longevity and magnitude.

We have also drawn inspiration, solidarity and admiration from other student unions and publications leading this struggle across borders and oceans. When students at New York’s Columbia University became the first in the world to establish their encampment, the Columbia Daily Spectator set the reporting standards. The paper’s first article was a photo essay capturing scenes from the encampment’s initial 24 hours. When a second encampment was established at Portland State University, Vanguard responded with daily TikTok updates about key political developments. The City College of New York’s paper The Campus Magazine has also responded with livestreams of arrests, encouraging students to scrutinise police who have active cases of brutality and violence against them. Other tactics, including The Daily Californian’s 24-hour coverage and The George Washington Hatchet’s regular op-eds, centred student media within broader pro-Palestinian activism.

Those camping are amongst those closest to us: our friends, our partners, our reporters and members of our editorial team. Not only are we provided with unique and intimate editorial insights into the function, structure and purpose of the encampment through these connections, but this movement is deeply personal. It is a moment in history. It is a reckoning for the future. Yet most importantly, it is a drop in the ocean right now in the fight for a Free Palestine: from the river to the sea.

Myth-busting

Critically, mainstream media outlets eclipse some of the key voices vital to the Gaza solidarity encampments: those of students. In its unique position to amplify these voices, Honi interviewed a number of student activists and campers hoping to share their experiences and dispel some of the most pervasive misconceptions.

When asked how the average reader of Australia’s most powerful news sources feels about the encampment, camper Luke Mešterović used one word: “confused.” He stated that “most of the mainstream media outlets are not outlining our specific demands, which are incredibly targeted at the University based on their ties with weapons manufacturing companies and Israeli universities in breach of international law.”

Mešterović went on to say that some readers “would also be under the misapprehension that we are somehow anti-semitic”, which he emphasised is “absolutely not true.” Besides the fact that security and management “have not had any concrete reports of anti-semitism from our camp”, Mešterović pointed out that it is “disgusting that during a genocide, our enemies have to try and slander us.” Fellow camper Ishbel Dunsmore concurred with these sentiments, highlighting that some outlets have tried to “get a reaction out of us” and condemn protesters for what she called “the crime of standing up for Palestinians and calling for freedom and justice for all.”

Campers like Tyberius Seeto, the current Editor-In-Chief of UTS’ student publication Vertigo, recognise the encampment for what it is: an expression of solidarity. Amidst media portrayals of the encampment as “anti-semitic” and therefore “very vile, very aggressive and very intimidating”, Seeto underlined that “this is a pretty horrific accusation to make because we have Jewish people who have spoken and who are camping out.” Seeto also emphasised the role of on-campus reporting as a “medium of change” beyond the mainstream. “We are technically the voice for students. We are elected by the students”, Seeto told Honi. “We need to get students to see and read what is happening.”

Impact on Campus

The students Honi interviewed felt that the success of the camp outweighs and disproves the accusations made against it. For student activists like SRC Ethnocultural Officer Ravkaran Grewal, “there’s a real sense that we actually have some power here for the first time in a very long time.” Grewal pointed out that protesters are “pulling rally numbers we haven’t seen in years, or even decades. There is a massive community behind us that’s been supporting us constantly.” The University’s ties to weapons manufacturers represents “something we can target and make a difference towards”, and the encampment is just one way “we can stop the Israeli war machine and help the people in Gaza.”

Each student agreed that this is a moment of left-wing unity for the SRC and student politics more broadly. Grewal noted that “this is the first time in a while that we’ve seen all the leftist groups on campus, bar Labor Left, come together and actually be in the same space.” For Ishbel Dunsmore, this is also the first time “in a long time that we’ve drawn such a broad crowd, where everyone is working alongside each other for a common goal.”

But beyond its importance as a watershed moment in the University’s history of radical student politics, the Gaza solidarity encampment provides a symbol of and for the community. Mešterović described his experience camping as a “direct and public” form of activism that has been “an incredibly positive and educational experience.” It has been marked by a “greater sense of camaraderie amongst each other”, not just alongside other students with whom he has been “making breakfast or doing hot water runs”, but also the “public support we have received from passersbys.”

Grewal’s final comments to Honi expressed hope “in the power of the youth to tell it like it is”, those who are “standing up for something” and can “galvanise more mainstream audiences.” In his own words, this is “actually not that complicated of a story” for readers of mainstream media to grasp; if it is easy for “supposedly ‘naive’ and ‘innocent’ university students to come to the conclusion that what Israel is doing in Gaza is genocide”, then we should “accept that it is.”

Management

The rhetoric published by mainstream news outlets also informs USyd management’s correspondence with students and staff, in which Mark Scott often cherrypicks select instances of intimidation or interference: such as a third party truck driver allegedly using offensive language. A dot-pointed list of these alleged occurrences feeds into some students’ beliefs, compounded by media narratives, that encampments are sites of violence and bigotry, rather than peaceful protest and education.

On Day 11, Vice-Chancellor Mark Scott notably rejected calls from Shadow Education Minister Sarah Henderson to send police onto the University’s Camperdown campus. In a LinkedIn post, he stated that “I am not convinced what is happening on US campuses demonstrates a pathway to greater safety and security for any students or staff, nor helps to build a community committed to free speech and thoughtful exchanges of divergent views.” On the same day, he published an op-ed in The Sydney Morning Herald defending the encampment as “part of who we are.”

Yet Scott’s moral defences in mainstream media are markedly different from those students have seen on the Quadrangle Lawns, and its backrooms. On May 8, Students Against War (SAW) posted a video attempting to confront Scott on Eastern Avenue. In the video, activists from SAW can be heard asking Scott “so when are you coming down [to the camp] to chat to us about our demands?”. Filmed with his back turned and walking away from the camera, Scott responds “we’ve got people standing by ready to.”

However, it is Scott’s silence in response to students’ demands which remains the most deafening. In an Open Letter to the University of Sydney on May 15, organisers of the encampment condemned University management’s failure to “discuss our demands.” Although campers regularly receive communications emphasising the “necessity to meet privately in a ‘neutral’ setting”, organisers reiterated their “counter-offer”: “we will meet with you to discuss our demands in one of the following two settings. An open meeting at our encampment, where all those attending the camp will have the right to witness the meeting. Or, a Town Hall meeting open to all staff and students.”

The Open Letter was signed with a proposition to meet at “10am on Friday at either location.” Mark Scott, and other members of the University’s management, failed to make an appearance at this meeting on May 17. At the time of writing, the petition for a Student General Meeting with University management is only missing 150 signatures from the 2,000 signature threshold.

This comes one week after Scott joined other Chancellors from Australia’s Group of Eight to ask Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus for legal advice on encampment demonstrations. While Dreyfus affirmed that “no one in Australia should be targeted because of their race or religion” under the Racial Discrimination Act, he concluded that he would not make a ruling. Consequently, universities are required to make their own decisions about chants, protests and the longevity of the encampment.

Protestors and campers have also told Honi that University management have attempted to ‘catch them out’ on WHS breaches in recent weeks. Campus security liaisons, which are stationed at the encampment around the clock, have warned students in particular about the risks of sharing their swipe cards to access amenities facilities in Fisher Library and other buildings which are locked overnight. The Quadrangle’s main gates must also remain accessible to emergency services, which has prompted the relocation of food and other camping materials around the site.

What are USyd’s ties to Israel?

Education

Many encampments criticise their institution’s educational ties with the Israeli tertiary sector. Interestingly, the inter-university relationship between Australia and Israel is not facilitated on a case-by-case basis; rather, it is consolidated on a national level. In 2013, Universities Australia signed a Memorandum of Understanding between Israel and Australia on cooperation in higher education, which SydneyStaff4BDS have called for the withdrawal in an open letter in November 2023.

Student opportunities at USyd include an international placement for Doctor of Medicine students where up to $5,000 is offered in an elective term scholarship for Technion — Israel Institute of Technology. This is in addition to the Experience Israel Travel Scholarships, which goes towards the OLES2155: Experience Israel unit at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem as well as study abroad programs at Tel Aviv University, Bezalel Academy of Art and Design (College of the Arts) and the recently established New York University (NYU) Tel Aviv.

Why should we care about ties to these universities as opposed to universities in countries that also commit atrocities? These Israeli universities do not only operate on and profit off from stolen land: they perpetuate dispossession. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Mount Scopus campus is partially built on land illegally expropriated from Palestinian owners in Israeli occupied East Jerusalem, in clear violation of international law, and therefore directly serves the ongoing land theft and dispossession of Palestinians. Hebrew University also has offered its campus buildings to Israeli forces, and hosts a military base on campus to offer academic training to Israeli soldiers. Tel Aviv University sits on the ground of the destroyed Palestinian village of Al-Shaykh Muwannis and Yaffa, running joint centres with the Israeli military and arms industries. Bezalel Academy of Art & Design set up a workshop on campus to design and sew uniforms and gear for Israeli combat soldiers serving in the Gaza genocide.

Other universities have since cut ties with Israeli universities following campaigns from their student unions: the Dutch Royal Academy of Arts, Design Academy Eindhoven, Netherlands and University of Bergen’s Bergen School of Architecture have all severed or frozen ties with Bezalel Academy of Art & Design.

Military

The Defence Innovation Network (DIN) is “a university-led initiative of the NSW Government and the Defence Science and Technology Group to enhance NSW & ACT Defence industry capability through collaboration with government and academic research institutions”. Established in late 2017, the DIN office resides in the UTS Industry Hub and is supported by nine universities, including USyd, to benefit the defence sector and contribute to technological innovation, whether that be through research and development (R&D), “foster[ing] collaboration between NSW industry and universities” or providing “pathways to STEM careers in defence”. This contributes to the trend of hypermilitarisation within Australian universities under “defence-oriented” frameworks to produce research with funding from weapons companies or war profiteers, even if it is not always used in an active military context.

Established two years after Belinda Hutchinson was appointed as Chancellor, USyd signed a Memorandum of Understanding with French arms manufacturer Thales. At the time, Hutchinson was Chair of Thales Australia. It comes as no surprise, then, that Thales has provided direct funding into research for low altitude air traffic management, drone operations and underwater situational awareness across multiple disciplines at USyd including Aerospace, Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering. Those working at the Nanoscience Hub have previously stated that these research spaces are for “private knowledge or military knowledge that is locked away under non-disclosure agreements.”

How does this translate in ties to Israel? The Israel-Australia relationship is documented by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade as including a “system of major global investors, start-ups, the Israeli military and universities”, confirmed by the 2017 Technological Innovation Cooperation Agreement and the Memorandum of Understanding on defence industry cooperation.

Thales, and by extension USyd, have strong ties to Israeli weapons manufacturing and deployment. In 2021, Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) partnered with Thales to develop new surface-to-surface guided missile technology. Named ‘Sea Serpent’, the missile combines anti-ship, RF seekers and land attack capabilities to pursue ranges over 200km. Simultaneously, Thales partnered with Israeli company Elbit Systems to develop Watchkeeper drones, modelled off older iterations of Hebron combat drones regularly upgraded by IAI. Green Left has since published that the Thales-Elbit partnership involves a subsidiary company UAV Tactical Systems, which manufactures “killer drones.” These three technologies have all been used extensively in the bombing of Gaza.

In November 2023, USyd signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Safran Electronics & Defense Australasia, a subsidiary of aerospace and defence company Safran, for a “focus on aviation, space and defence solutions”. Safran works with Rafael, one of Israel’s top defence companies, to develop battlefield technology for the efficient identification and neutralisation of targets.

Furthermore, the Gradient Institute is a research hub “enabled by the vision of CSIRO Data 61 and University of Sydney” which is “developing new algorithms, training organisations operating AI systems and providing technical guidance for AI policy development”. This “strategic partnership” comes under the DIN surrounding areas of data analytics, autonomous cyber technology, and information warfare operations. During the Australia Israel Chamber of Commerce 2017, Data61 was celebrated as a key strategic achievement as well as the 2021 Australia-Israel Innovation Summit, where a panel was held on “AI and the impact on industry”. USyd Chancellor David Thodey, and former Chair of the CSIRO, also spoke at this summit in a panel “consider[ing] instructive lessons from the Israeli experience in building globally-renowned innovation centres of excellence”.

Is the university likely to divest?

University of Melbourne Deputy Vice-Chancellor Michael Wesley recently stated to The Age that if universities divested from weapons manufacturers, what would follow is a severance of work with “fossil fuel companies…supermarkets…manufacturers of sugary drinks”. So it appears at present that there is a lack of political will to do so.

Most of Australia’s universities are publicly funded — only three are private (Australian) and two are private (international). Australian universities receive funding primarily through government research, teaching grants, and student fees supported by HECS-debt. Other sources include state government funding, overseas student fees, investment income, plus contract research and consultancy income.

However, a 2022 report from the Australia Institute’s Centre for Future Work shows that because of higher enrolments and decreasing funding, Australian universities have increasingly turned to private and corporate sectors. Despite this, Australian universities are less reliant on endowments — pools of assets that originally come from donations and are then invested elsewhere — than their US counterparts.

Robert Reich, Professor of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley, noted that American universities are faced with questions of autonomy, especially as a large role of university presidents “is to solicit money, and their largest targets are typically… Wall Street”. These presidents have been pressured to convey strong anti-encampment stances and clear condemnation of October 7 to ensure funds are not withdrawn. For example, Apollo Global Management CEO Marc Rowan demanded the University of Pennsylvania (UoP) president and chairman of the board of trustees resign, and then asked others “to reduce their normal contributions to the university to just $1 ‘so that no one misses the point’”. This indicates that universities function like corporations, and are beholden to donors who act like shareholders. In the US, philanthropic funding is at its peak; Harvard’s single largest contributor to revenue, contributing to 45% of the $5.8 billion in income in 2022.

While it does remain difficult to ascertain how much assets are tied to Israeli corporations and the Israeli Defence Force based on research and public information alone, the need for universities to provide greater transparency when disclosing this information remains pertinent.

Divestment may seem a distant reality but the examples of the Union Theological Seminary divesting to avoid financial support of “damaging and immoral investments” and the engagement with encampment demands at Brown University, Northwestern University and the University of Minnesota prove that it can be possible.

Where do we go from here?

At the time of writing, the University of Melbourne has given Victorian police explicit approval to intervene in its encampment at any time. While others such as Monash University have ended their camps, many remain strong and are pinning management down with the pressure of escalating demands. Regardless of whether management decides to divest or not, it is clear that power still resides with the student body to challenge the tertiary sector’s hidden ties with genocide.

Additional information has been provided by Students Against War, USyd Education Action Group, and UniMelbforPalestine.

—

UPDATE: As of 20/5, a Freedom of Information request submitted by Students Against War ANU revealed that the Australian National University (ANU) has over $1 million invested in contracts with weapons manufacturers implicated in the genocide via their ties to Israel — Boeing Co, Saab AB, Thales SA, Dassault Systemes, IBM, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and BAE Systems PLC.