The past month has virtually exposed me to some iconic European beaches as a lot of my Australian mutuals found themselves amidst their silly summer escapades in the Mediterranean. Similarly, I was dripping in sweat on the beaches of Goa and Mumbai, gnawing on fried mackerel and sipping toddy at local shacks by the beach. What is common between these summer images is the proximity to water: both European beach bars and Goan shacks boast proximity to the sea, with people sipping on their drinks while resting on their beach beds. As a summer country that projects a distinct beach culture for tourists and residents alike, Australia seems curiously averse to sea level revelry. Why is it that the beach kiosks, bars, and local food joints all happen to be one street back from the shore?

Attempts to emulate the European beach life on Australian shores are not unheard of. In 2020, controversy engulfed the proposal for the Amalfi Beach Club on Bondi Beach, which was largely opposed by Australian beach-goers (including the Italian diaspora) on the grounds that it would privatise an otherwise open public space. The plans to charge roughly $80 for a sunbed, cabana, and umbrella, allowing visitors to enjoy a leisurely drink by the bar on the sea, was seen as a danger to the otherwise free Australian beaches.

The free public access to the coast without the overt demarcation of public and private land like on many European beaches is undoubtedly a pleasurable experience and integral to equitable access to our public spaces. However, arguments that paint the Australian beach culture as sacrosanct in terms of equity are not as straightforward as they seem.

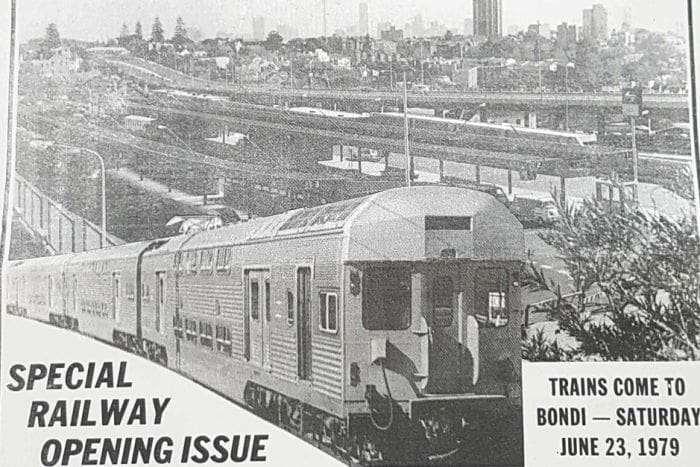

A railway line directly connecting Sydney’s West to the eastern beaches was proposed in the 1920s to reduce the inconvenience of road travel. According to the Australian Historical Railway Society, protest groups like Not in My Backyard and Save Bondi Beach Incorporated raised concerns over issues like overcrowding, increase in crime rates, and rubbish in their “haven” if an influx of people from other neighbourhoods were to occur. In addition to people protesting on the streets, leaking the fuel pipes installed on the railway, and shutting down access to the beach, the State Government also denied funds for the completion of the project. A century later, an influx of locals at the beaches violating COVID-19 social distancing rules highlighted the striking divergence of accessibility to the beaches among the city’s residents.

What does the Australian beach culture comprise, exactly? Is the lack of private beach clubs on the coast the only parameter of a truly equitable beach?

While beach bars are just a singular aspect of the debate over beach accessibility, the issue does raise questions about the complexity of access and the apparent sanctity of the areas for long-time dwellers. Residences around oceans are an expensive real estate affair, with beachside homeowners commonly endowed by generational wealth or ludicrously well-paying jobs to achieve their ocean-vistaed dream. This naturally makes the beaches a fascinating detour for those away from the areas, usually attracting large groups or families.

Most permits to build a beachside bar, set up umbrellas, seating and food service are given on a trial basis as seen in the case of Kurrawa beach club on the Gold Coast. Although many conventional images of beach culture or fun on the beach focus on alcohol or hardcore clubbing, this is not always the case. Instead, beach clubs offer many possibilities for unique community experiences or tourist attraction.

When I saw groups of middle-aged Lebanese women roasting corn on the cob in the middle of the beach at Brighton Le Sands, it sparked a similar feeling to watching vendors selling dry snacks and balloons on the beaches of Mumbai.

Matt Thistlethwaite, the ALP Federal Member for Kingsford Smith, tweeted in April 2021 saying that exclusive areas on beaches encroached by companies are not a part of “our culture”.

Unfortunately, the obsession with keeping private companies off Australian beaches doesn’t create a truly equitable culture. Instead it camouflages the inequitable, classist, and racialised history of access to our beaches.

Even though the politics of urban planning is hardly straightforward, the element of public enjoyment is intrinsic to a public space that brews a culture that is inclusive of people. Destinations like Phuket have created demarcations of spaces segregating places where vendors are allowed to sell umbrellas, mats and other water sport equipment, with the other areas strictly reserved for beachgoers. While the overt demarcation in places does risk an upsurge in surveillance and policing in these spaces, leeway for businesses blooming by the sand may foster outdoor hospitality and a new kind of freedom.