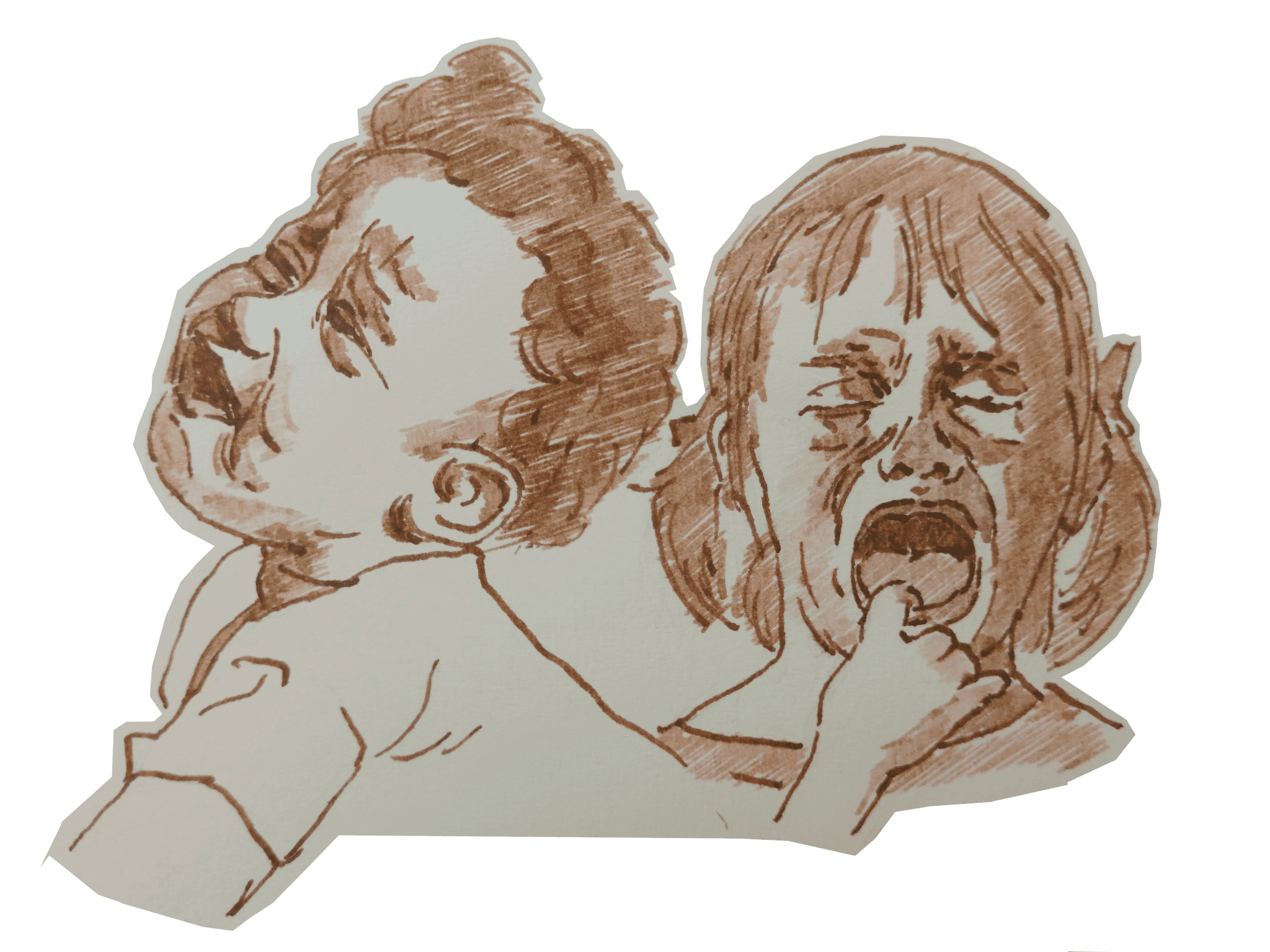

A child is crying on this bus and all I want to do is get off. I have never heard such a distressed shriek in my entire life, a pitch so piercing it drowns the droning motor and pixelates the passersby. It replaces the air, gasping and incessant, yet everyone here pretends not to hear it. I keep my head down. I steal a glimpse at the child’s mother — there is always a mother. She presses the stop button when I do, manoeuvres the pram onto the curb, and does not look back. I wonder if she is crying too.

***

In her novel, Motherhood, Sheila Heti asks: “Why are we still having children?”. Following the internal conflicts of guilt, wonder, and longing she experiences watching her peers nurture their families, Heti’s narrator agonises over if, and not when, she will ever do the same.

I had never felt so heard by someone else’s voice. As a young woman who has whispered this question to herself almost daily since first reading it, I believe there might never be a good enough answer that I can give myself. Instead, I must be dragged, kicking and screaming in the same way I was when I learned the Easter Bunny did not exist, to this decision I do not think I will ever be ready to make.

Some of my first memories are of my mother caring for me. My following memories are of myself caring for my younger brother. Four years his senior, I trickled water across his forehead and sang to him between splashes. As we grew older, I sanitised his baby bottles and taught him how to walk. Even now, as I watch him leave for school in the early morning glow, I hear gurgles amidst his giggles.

This is not a matter of loving a child that shares my blood. I am human, and I would do anything for my family. But I am also a woman, and by the time I was ready to start preschool, I was known as my brother’s “second mum.” I learned quickly that the love I know I can give, so full and overflowing that I sometimes do not know where to put it, will never just be warmth or affection. My love needs to be devotional, a force so nurturing and doting that I will inevitably lose myself to its howling demands.

I was fourteen when I first heard the phrase “biological clock”. The words came from my father, a condescending quip in the face of my longing for a career without a 13.3% pay gap. I had seen what children had done to every woman in my life: waiting for sleepless nights to pass, for bygone opportunities to come back, for the children they had raised to return home. While I know now that motherhood does not have to be overwhelmingly loud or blissfully silent, I would at least like to hear my own melody amongst it.

When I speak of a balance between my ambition and maternalism, I am not thinking compromise. I am the first woman in my whole family to attend university, and to see employment as a source of fulfilment and freedom. I acknowledge, too, that my treatment of motherhood as a choice is a privilege borne from the sacrifices made by my mother, her mother, and her mother’s mother. I bear the weight of their tears, through laughter and sorrow, in everything I am lucky enough to create.

However, if I have a daughter, she will inherit all the screams swirling inside me. I think now of Sylvia Plath’s journal from 1950, of her need to repeat mantras that “males worship woman as a sex machine”, that “wealth and beauty are not in your realm”, and that we are all angry and unhappy. My daughter will never know peace, and it will be my fault. Perhaps this is what I am most afraid of — not my own oppression, but the certainty that my love cannot overpower it.

Of course, it is one thing to claim that I do not want to have children. It is another to be told that I cannot. Since my PCOS diagnosis, visits to my doctors have been dominated by questions about my fertility. Here I am, filling the devastating holes I thought only a child could create. This note in my future has been played too early, like a tremoring trombone that cannot tune itself.

It is not that I feel I will be less of a woman without children. It is not even that I do not want them at all. I want to be a parent, not a mother. I want to be certain of why I did it and have enough love left for myself by the end of it. Above all, I want to hear a child crying and not find myself crying out for the exits.