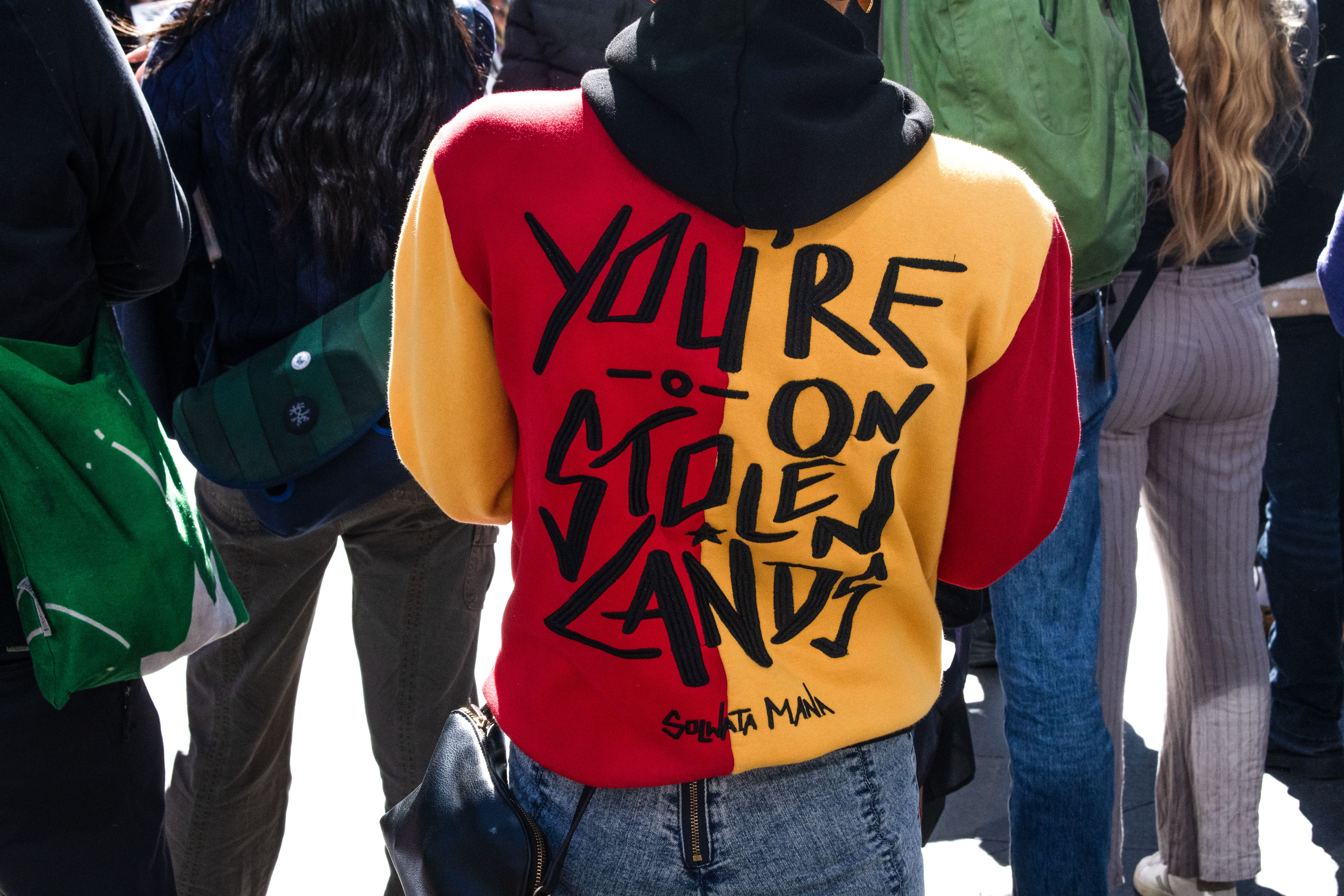

The steps of Sydney’s Town Hall were crowned in red, yellow, and black on Saturday as protesters reunited under the banner of the Black Lives Matter movement that captured the world three years ago.

Attendees echoed the very same calls for justice in addressing the overrepresentation of Indigenous deaths in custody as the watershed BLM protests did in 2020, where 20,000 Sydney-siders took to the streets in spite of burgeoning lockdown orders. Ironically, there was a notable discrepancy in attendance between those protests and this year’s post-pandemic rally, which attracted a turnout of about 100.

Organiser and Wiradjuri student activist Ethan Lyons spoke on the matter: “I find it sad that, in 2020, I came with a bunch of friends from high school — they would post on social media, they would post the black square, they were posting the infographics — yet, three years later when it’s not a trend, when it’s not on social media, they aren’t here.

“First Nations people, Blakfellas, are forced to live through that every day — they don’t get a break. We can’t just log off social media.”

Indeed, support for the broader Black Lives Matter movement has fallen to an all-time low, according to findings by the Pew Research Centre in the United States. On home soil, the disproportionate use of police force against First Nations people has only risen from 2018 to 2022, representing almost half of all cases where police employed excessive force.

“We stood here at this exact same place back in 2020. We said that black lives matter and we demanded so many changes,” said Dunghutti speaker Paul Silva.

“We bawled our eyes out, we set our demands very clearly — yet, they still fell on deaf ears and blind eyes.”

Silva, who has been on the front lines of the movement for almost a decade, pleaded for an independent body to investigate future Indigenous deaths in custody following the death of his uncle, David Dungay Junior.

Dungay Junior was fatally restrained by multiple guards in Long Bay Correctional Centre, after repeatedly pleading that he could not breathe, in December 2015. Dungay Junior’s death mirrors that of George Floyd but, like many other Indigenous fatalities, he has only received a sliver of the public’s attention.

Other speakers advocated for the recognition of injustices against First Nations people beyond the prison system, particularly in regard to the healthcare sector. Ricky Hampson recounted not only the pain from the death of his son Ricky “Dougie” Hampson Junior — who was fatally misdiagnosed and discharged from Dubbo Base Hospital in 2021 — but the strenuous inquest that followed in search for peace and justice for his family and community.

“This health system is killing our people off slowly as well, and not a lot of people know about it,” said Hampson.

In response, protestors called for the implementation of all recommendations from the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, the closure of Indigenous-overrepresented youth prisons, and for justice when dealing with deaths in custody.

Protesters marched along George Street to the NSW Supreme Court to advocate for such demands, drawing questioning looks from passersby. It seems that the Black Lives Matter movement, three years removed from its peak, has now become an unfamiliar concept for many.

The organisers were deliberate in refraining to align with either camp of the upcoming Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum, with speakers advocating that — regardless of a Yes or a No outcome, mass mobilisation is crucial in the ongoing fight for better outcomes and justice.

If support for the Voice within First Nations communities appears ambiguous, Lyons made one point very clear: “we cannot wait until another Invasion Day rally to mobilise on the streets,” Lyons said. “This is an ongoing genocide against our people.”