“I’ve been looking so long / at these pictures of you / that I almost believe that they’re real.”

– Robert Smith

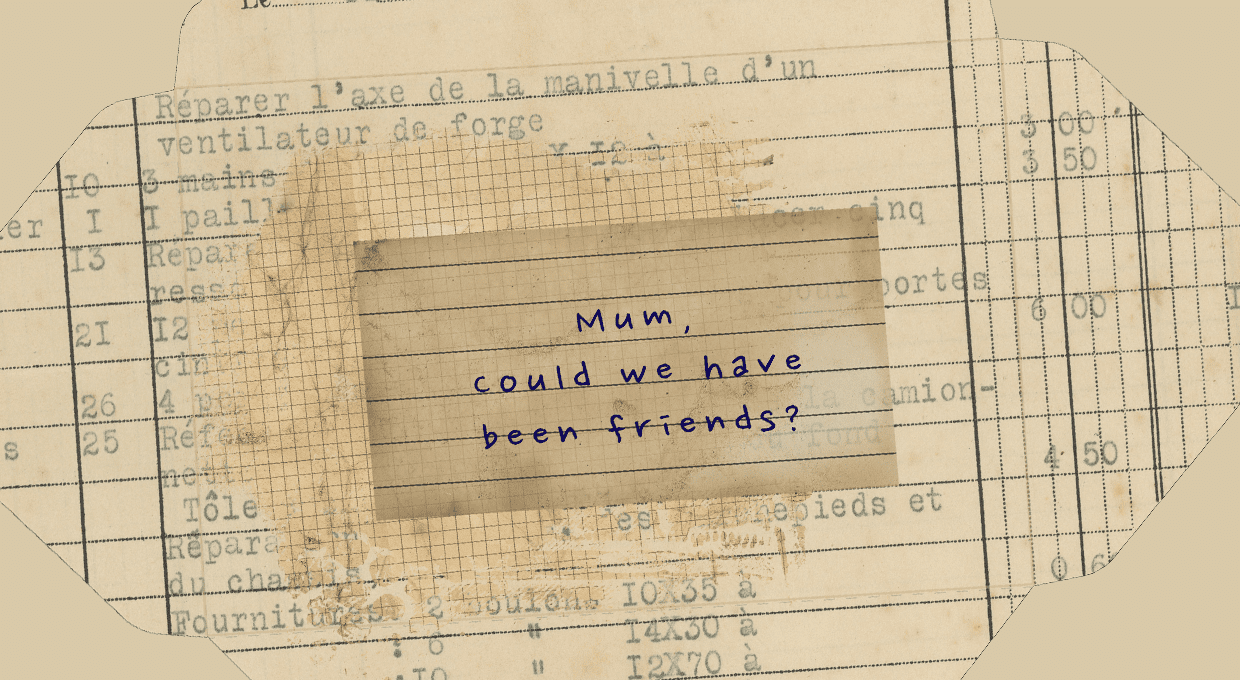

I’ve spent a lot of time wondering whether me and my mother would have been friends. If I could somehow achieve the Gen Z fantasy and go through a wormhole to 1989, would me and some kid from Asquith have gotten along? I’ve imagined it so many times. A grimy, raw Sydney street from a cheaper, cooler time. I skip the line into Sanctuary night club and start asking around for her. “Hey, do you know Steph?’”. The myths and monsters of her stories appear: skinheads, sharpies, punks, new mod wannabes, Morrissey disciples, wasted junkies and one tall redhead called what’s-his-name.

She’s with a crowd of other goths, perched on a couch with a cigarette she got off the guy she’s dating. She once told me that when he finally told her to get some of her own, she put the money in the machine, but changed her mind at the last minute and walked away without the carton. She tells that story when we talk about smoking.

I’ve seen her outfit before. It’s one I’ve seen her wearing in a photo taken at Waverley Cemetery. A black t-shirt and long velvet coat. My imagination gives her a vague veneer of ‘goth’ — white makeup and a dour regality. Her hair is Robert Smith’s spiky black mop, her jewellery is Vince Noir’s in season 3 of The Mighty Boosh. She’s the coolest person you’ve ever seen.

In this way I construct her out of raw materials — tv shows, books, stories — trying to build an image of her where I might see myself reflected, however faintly.

As we grow up and become more independent, we learn to understand that our former caretakers are complex individuals with their own stories and histories that have nothing to do with us. The stories become less sanitised, scandals are rediscovered in more gruesome detail, family squabbles more tragic. Tense Christmas lunches of years long past develop a rich contextual happenstance. Before a certain age, I had no idea how long an argument could simmer between distant cousins, or the generations of British people that cheated on each other long ago to result in my birth.

I know that my imagination of my mother’s life, the approximation of her built out of the most glamourous characters from her favourite books and movies, can only be a pale imitation of the life she has lived. It pains me that I will never know everything about her the way she knows everything about me. I am always looking for her in me. I wonder how often I emulate her, what little habits I unknowingly copy or similarities of thought that have passed down without me knowing. I sometimes wonder if she holds her life up to mine and marks the differences like I do.

“Mum, if we had met, would you have liked me?” I ask, trying to sound casual. She spies me over her reading glasses, distracted from a chopping board or a novel she’s tearing through for the hundredth time. She gives a chuckle, and I can hear a dozen thoughts mixed into it.

“We would have moved in very different circles, darling.” she says, and my heart aches.

When you love and admire someone so much, how is it to be borne that you can never really know what they’ve been through? My mother’s stories about our family are integral to how I’ve built my world and my place in it. When I lose myself, I go back to her. And who is she?