“I don’t want to see protests on our streets at all, from anybody” — Yasmin Catley, NSW Police Minister

Long before her arrest, Violet Coco knew that she’d be going to prison. The 33-year-old environmental activist was sitting at a friend’s table, when the news broke that the NSW Government had passed draconian restrictions on the right to protest in the state.

“It was an intense day, that was the day that I knew I would go to prison because I knew that I wasn’t going to stop without serious action.”

Just four years ago, Coco had sold her successful events management business and committed her life to environmental action organising. While strongly associated with Extinction Rebellion, she also distributes her energy across many other groups. “I guess I’m sort of a bit of a freelancer. I just jump wherever the action is,” she said.

She would go on to be the first person to be charged under the anti-protest legislation in April 2022, when she staged a climate action on the Harbour Bridge and blocked the flow of traffic.

“Once I was arrested, they put me in the back of the divvy van and then held one of the others who was on the road with me just outside the divvy van for about five minutes under pain compliance,” said Coco.

“I could see her being tortured and neither of us could do anything about it.”

Coco spent the subsequent days in police custody where she says she was denied access to food and toilet paper, and threatened with sexual violence before being released into 24/7 house arrest.

“Eventually, I was able to get a bail change so I could get out, but even then I was largely confined to my home,” she said.

“My apartment at the time was a one-bedroom house with no garden or anything, and I had non-association conditions with my community so I was incredibly isolated, I became very unwell, and so I changed my plea from not guilty to guilty and as soon as I did that they removed my bail conditions.”

Following her guilty plea, Coco was sentenced to serve 15 months in prison.

She would go on to have her sentence quashed on appeal after it was revealed that NSW police had provided false testimony that Coco had blocked an ambulance during her protest on the Harbour Bridge. This false narrative, constructed to villainise Coco, is reflective of the state’s law enforcement’s long and complicated history with protest movements.

“It was because of that lie that they were able to keep me under house arrest,” she said.

Through a long smear campaign, Coco has become the poster child for civil disobedience. However, the activist believes that the attack is not personal, arguing that state forces are cracking down on the environmental movement at large.

“The fossil fuel industry has a strong hold over our government systems and they obviously do not want us to be trying to shut them down and so they have the political power at this stage,” she said.

“We’re in that struggle between people power and political power.”

—

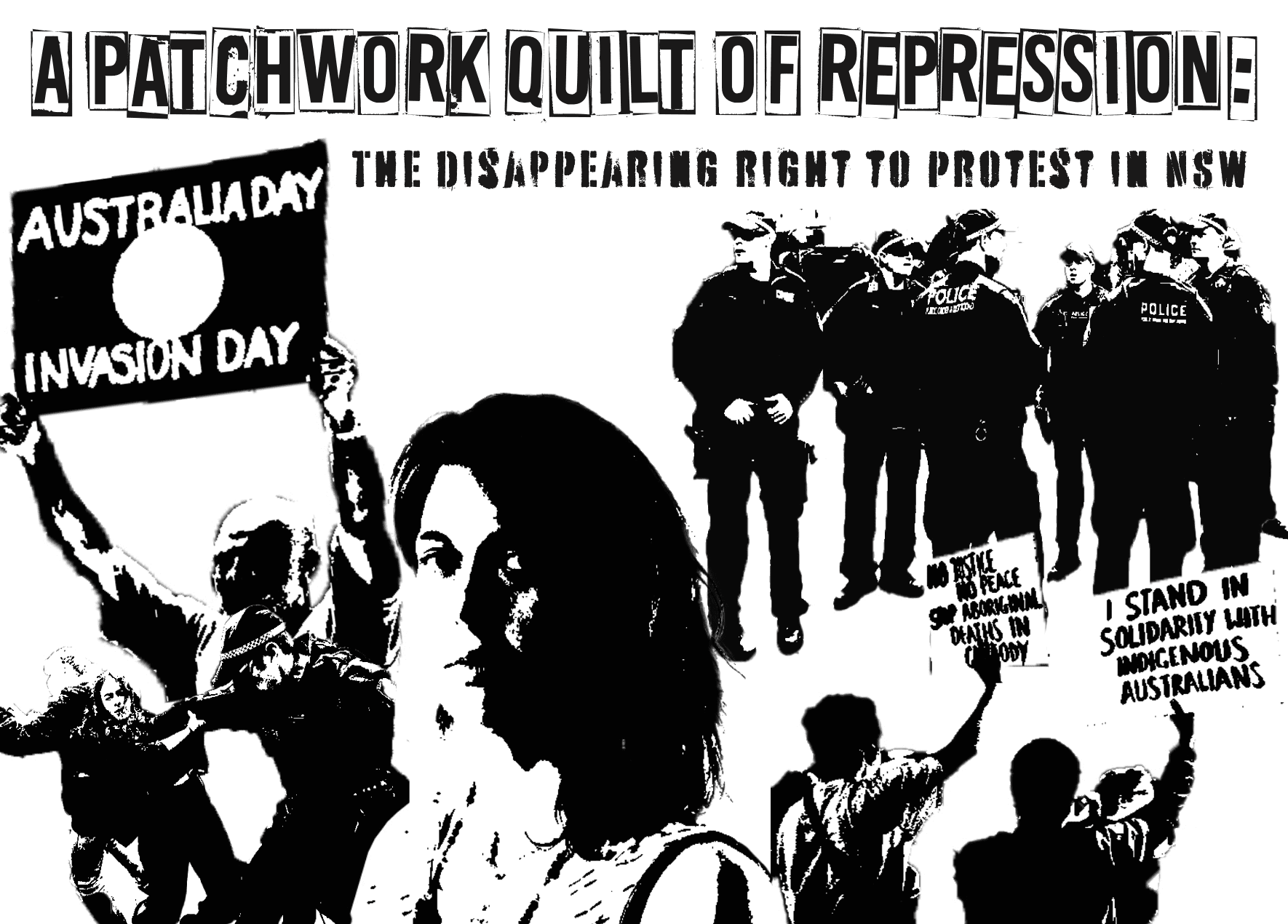

Josh Pallas, President of the New South Wales Council of Civil Liberties, describes the laws restricting protest in NSW as a “patch-work quilt.”

In 2022, the Coalition government, with the support of the Labor Party, passed the Roads and Crimes Legislation Amendment Bill 2022. The bill amended the Crimes Act, to allow activists like Coco to face fines up to $22,000, sentenced to two years in prison, or both, if they trespass or block a “major facility” and cause damage, serious disruption, closure or redirection of people from the facility.

But the Bill is only one part of a “tranche” of legislation going back to 2016, Pallas said.

In 2016, Premier Mike Baird passed laws that increased the penalty ten-fold for trespassing with intent to interfere with business to a $5,500 fine. He also enabled anyone “interfering with a mine” to be imprisoned for seven years. In 2018, the Berejiklian government enabled police to prohibit people from “taking part in any gathering, meeting or assembly,” on Crown land, which makes up 40% of all land in NSW, including Hyde Park and Bondi Beach.

The net effect of these laws, Pallas said, is that “it is actually becoming quite difficult to protest anywhere at all in NSW.” He noted that the new laws prohibit blocking or obstructing all of the train stations in the CBD.

“If you are protesting outside Town Hall, you are blocking entrances to Town Hall Station. Or at Martin Place, you are blocking Martin Place Station. In Hyde Park, you’re potentially blocking St James Station. Protesting in all of those places is now criminalised.”

Pallas said it is also illegal, due to the obscure Placemaking NSW regulations, introduced in 2020, to protest along large parts of the Sydney Harbour foreshore, including Circular Quay, Barangaroo and Darling Harbour.

“There are now very few places where you can now gather, as a mass group of people, without falling foul of these regulations. There is perhaps some sort of residual space where people could engage in protest as a matter of legal technicality, but they are generally places that are difficult for people to gather in number or places where it is difficult to demonstrate to the government.

“That doesn’t stop activists from protesting and they will continue to protest and they should continue to protest run up against these laws. But it certainly makes it harder to engage in it lawfully.”

Coco shared the same sentiment, stating that the protest movement “might take an initial hit because of the fear of men with guns but hopefully, they see the value and importance to the movement and step up through that.”

The restrictions on protest are not a NSW-specific phenomenon. Since 2019, Labor governments have passed laws targeting environmental direct action in Queensland, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. A Liberal government has passed them in Tasmania and environmental protest is being strictly punished in Western Australia.

The blatantly anti-democratic laws, Australia-wide, need to be repealed.

The fact that they even came to be is a dark reflection of Australia’s broken and decaying political culture. What, aside from repeal, needs to be done to protect the right to protest and support effective political activism?

—

For Jon Piccini, an Australian Catholic University-based historian who has studied protest and human rights in Australia, the recent expansion of anti-protest laws is not a historical anomaly. Australia has long seen attempts to restrain political resistance.

“It goes back a long way,” Piccini said. “Australia was established as a penal colony, as a part of the invasion of the land, so certainly there have always been laws to limit people.”

Pallas agrees. “I see more continuity than change … The military mode of colonisation means we have a far more repressive criminal law than even the UK.”

Piccini tracked this repression through the 20th century.

“In Queensland, there were bans on protest, often using the Traffic Act.

“The Traffic Act was designed to ensure the free flowing of traffic on city streets, but often that was just used as a blanket way to ban protest. That happened in the 1940s, by the Labor Government, during a high point of industrial protest after World War Two.

“Again, in the 1960s, the Traffic Act was used to ensure that protesters, particularly protesting students from UQ [the University of Queensland] couldn’t interfere too much with the running of the city.”

Whether protest laws were used to stop industrial, student, or environmental activism — as occurred under the Bjelke-Peterson government in the late 1970s — Piccini noted that “there is always a connection between the laws and the context in which they are made.”

Often, he said, “the laws are used as part of the theatre of politics. Governments use a heavy hand on a small number of activists in order to show they are protecting the peace. They are used to convey a sense of strength.”

Indeed, the NSW government media release announcing the increased penalties for protesting boasted that they would be “protecting communities from illegal protestors.”

Despite the Labor Party owing its existence to the protests of the union movement, Piccini notes that the Party’s current support for harsh anti-protest laws, be it in opposition or government, is not without precedent. “If you look at how the progressive wing of Australian politics has acted, it has often really crack[ed] down on the radical edge.”

This is because, Piccini continued, “the Labor Party is not a coherent whole.” He cited the Australian Workers’ Union’s attempt to “smash” a Communist Party-led strike by North Queensland sugar cane workers in the 1930s as an example of tensions between the left and right of the labour movement. (In 2022, the state Labor Party passed the increased protest penalties despite Unions NSW describing them as “unacceptable”.)

“Certainly, some progressives more to the centre move to protect their turf, and see any threat from the left as being something to which they will need to use administrative legal manoeuvres in order to contain,” Piccini said.

“Protest laws are part of a bigger continuum of the use of legality and bureaucracy to enforce a centrist ideal.”

—

A criminal law that represses civil liberties (such as protest) may be a feature of an invaded, colonised, penal colony. However, how is this consistent with the Australian state’s image as a modern democracy? It isn’t.

The primary justification for the laws is that protestors should not have the right to disrupt people and major economic activity. Pallas and the NSWCCL contest this.

“All protest is disruptive. The right to protest is fundamental to a whole heap of fundamental rights: the freedom of thought and conscience, freedom of assembly and association and the fundamental right that we have to participate in our system of democracy,

“Protest is one of the few ways that individuals can directly engage with lawmakers collectively.”

In Coco’s case, NSW Police justified her prosecution and conviction with the lie that her protest blocked an ambulance. The Attorney-General in the South Australian Labor government, Kyam Maher, used the same far-fetched rhetoric about ambulances in justifying the state’s similar laws.

But as Pallas pointed out, the disruption caused by the protests which the laws seek to prevent is “usually proportionate to the harm caused by the actions they are protesting against.”

“I find it really interesting when people talk about being disrupted by a couple of climate protesters,” Pallas said. “In Violet Coco’s case, one lane of the Harbour Bridge coming into the city was blocked. That’s one lane of a harbour bridge that’s usually blocked every morning by traffic.

“When there’s talk of disruption, it obscures the disruption that will occur [without the protests], the disruption of bushfires, the disruption of floods [and the climate crisis generally] is far more significant than the disruption caused by activists.

“There’s many different ways to affect social change. But there’s often nothing more visceral than people sort of taking to the streets and engaging in direct action.”

The decriminalisation of homosexuality, the eight-hour work week, and women’s suffrage, “were all brought about through protest and civil disobedience.”

As Blockade Australia, Fireproof Australia, Extinction Rebellion, and other activist groups point out, it is rather easy to stop the disruption of protests and (far more importantly) the climate crisis: by passing laws which stop the emission of greenhouse gases.

—

Due to the bi-partisan opposition to these arguments, activists have turned to legal remedies to invalidate the laws on the basis of their inconsistency with the system of democracy established by Australia’s settler-colonial and racially exclusionary Constitution.

In May, a constitutional challenge against the validity of the protest laws was brought before the Supreme Court of NSW by local environmental action group The Knitting Nannas. The Nannas are an “international disorganisation” made up largely of older women who stage “knit-ins” as their own brand of protest.

Two women from the flood and fire-impacted NSW mid-north coast, the Knitting Nannas’ Helen Kvilde and Dominique Jacobs, told the Court that their right to engage in protest was fundamental to advocating for their regional communities.

“If it rains, we get scared. If we see smoke, we get worried. One neighbour, a mum with three kids, is still living in a caravan from the fires. And our situation will only get worse,” said Kvilde.

Jacobs emphasised her fellow Nannas’ calls for urgent climate action, saying “we really need to be able to protest. It’s not illegal and they shouldn’t make it so. We need to be ramping up action to get things moving faster because we don’t have a lot of time left to make changes. That’s not going to happen at a system level without a big push from people in protests.”

During a climate protest in Port Botany in March 2022, Kvilde and Jacobs were both arrested for blocking roads.

In their dealings with the judicial system, they were introduced to the Environmental Defenders Office, a non-profit legal service that defended the duo after their arrest.

The EDO, now partnering with the Nannas in their challenge against the anti-protest laws, argued that the legislation is in direct conflict with the implied right to political communication found in the Australian Constitution.

“The explicit purpose of the law is to impose a burden on political communication, because it is perceived … a particular form of protest … should be prohibited and subject to severe penalties,” Stephen Free SC, representing the EDO, told the Court.

Indeed, Kvilde and Jacob’s arrest at Port Botany would look very different in the present day — on conviction, they received a conditional release order (CRO): a far lesser sentence than they’d likely be subject to now.

Speaking to Honi outside of the Supreme Court, Kvilde said that all citizens of NSW should be concerned about what the laws mean for our future.

“It’s a democratic right to be able to make a protest,” she said.

“I guess I feel that even if the laws don’t change, well, what can we do? The [climate] situation’s only gonna keep getting worse and worse.”

The outcome of the case will be unveiled in October. A High Court challenge against the laws could also be on the cards, given the complex issues of constitutional law involved.

—

It is clear that legal challenges alone won’t drag us from this position. Indeed, even a repeal of the recently passed laws will not solve the problem alone.

When it comes to the state’s response to dissent, explicitly anti-protest laws don’t exist in a vacuum when it comes to the state’s response to dissent. As Pallas described, the protest laws function as a “patchwork quilt of repression”, with the most obvious part of that quilt being the police force. Although police in Australia have long treated protesters with barbarity, they are becoming an increasingly deployed tool of the government to crush protests.

As part of the Coalition government’s passing of the Roads and Crimes Legislation Amendment Bill last year, it also oversaw the establishment of a Strike Force Guard to directly target environmental activists. This Strike Force can be seen “visiting” protestors in their homes before protests and staging violent and theatrical arrests. As was exposed on 4Corners, this type of police repression is not unique to NSW.

Part of the reason police hostility to protest has ramped up of late is because the protest laws serve an “expressive function” as Pallas put it: they show the police that the government wants them to crack down on protesters and that they will be supported if they do.

Piccini commented that “although these laws are often on the books for a long time they are often deployed at particular moments”. Anti-protest laws are only as effective as the zeal of the police force implementing them.

Aside from intimidation, the police use other legal tools. One of these is the use of bail to restrict the freedom of environmental activists. Police attempted to impose bail conditions on student activist Cherish Kuelmann earlier this year, preventing her from entering the Sydney CBD. As a magistrate ultimately held in Kuelmann’s case, they had no legal basis to do this.

The other is the use of the Summary Offences Act — notably the Form 1 process — which police use to disperse protest and even arrest protest, for trivial offences.

—

This patchwork quilt of repression may be derived from parliament and its enforcement to the police, but it owes its possibility to the voting public. A disappearing right to protest, ultimately, is caused by a political culture that is intolerant of dissent and disagreement.

“We’re expected to engage civilly all the time, on every issue. This push towards civility and decorum really squashes room for dissent, or protests. If we say that you can only disagree or dissent in certain ways, we end up with tacit acceptance for these types of anti protest laws,” Pallas said.

“We need to sort of regenerate norms around the way we have civil discussions in the public sphere and the way that we express dissent or disagreement.”

Piccini agreed, noting that protest movements themselves help generate a more active democratic culture. “It’s about the norms, but the laws. Protest movements facilitate a greater involvement — not just by the left but by the right — in politics, the sense that politics is not just for the parliament.”

Increased political engagement is not just important because it disallows politicians to so heavily crackdown on peaceful protest — polls show Australians strongly support a right to protest, for instance — but because it leads to policies which better meet the public good. The corollary of the public applying less pressure to politicians is that the pressure applied by corporate lobbyists is more impactful.

Pallas said, “at the moment there has been a coalescence around the influence of lobbyists and people with vested interests, and people with significant amounts of capital. And that is problematic for our governance because what is in the interests of lobbyists and money-making machines is not necessarily in the interests of the people the government is elected to represent.

“We know that’s the case when it comes to the protection of the fossil fuel industry and any industry that capitalises on the climate crisis, because the scientists are telling us that the planet is fast becoming uninhabitable.”

—

Violet Coco says that it is paramount that the Nannas return a victory for their efforts.

“There’s some really, really intelligent and powerful women and minds in front of that case, so I’ll definitely be watching closely,” she said.

“But it’s hard to have hope at the political will of this system of injustice to do the right thing, but I guess we gotta keep trying, and we gotta keep fighting for what’s right.”

It is clear when speaking with Coco that the activist’s experiences with law enforcement have not swayed her resolve, nor that of the environmental action movement.

“When I got sentenced to prison, we saw some of the largest solidarity amongst the movement,” she said.

“And that was really powerful because they recognise that it’s not just about me, it’s about all of us.”

Speaking about the relevance of the laws to students, she said “throughout history, the most powerful movements to shake up social change have been the uni student movements, and so it is not surprising to me that the government and the police are making moves early to scare students into submission.

“But I also know that the fighting spirit of people who have engaged minds are gonna see through that and are gonna rally through that.”

As we have seen this week — with the NSW Labor government said it would try to prevent a pro-Palestine protest on the basis it hadn’t filled out paperwork in time, then backtracked with police announcing their plan to use extraordinary powers to search protesters without cause — a lack of protections for protest doesn’t just hurt environmental activists, or students, but anyone who may disagree with the government.

Rebuilding the conditions in which protest can thrive unencumbered by overzealous police and a state which is intolerant of dissent is a project in which we all must play a part — in repealing protest laws, protecting the right to protest and in creating a culture in which mass engagement with politics is a norm. None of that can occur if the assumption that disruptive protest is illegitimate protest remains untouched.