Those who frequent City Road at night might notice a different pattern of lights illuminating from International House each week. Some days the lights in the dining room are on, but other days it’s pitch black inside. It piques curiosity. If International House was shut down at the end of 2020, then what is happening inside?

The only way to find out was to break in.

Once behind the fenceline, you have to find a way into the building itself. If you’re lucky, there will be an open door or a window that sits ajar. If not, you’ll have to get creative. When you make it in, remember the exterior of International House is almost entirely made of windows and — if you walk past one in a well-lit hallway — people will see you. Unless you want to take your chances with members of the public (or prowling University seccies), commando-crawling may be necessary. Don’t wear your Sunday best.

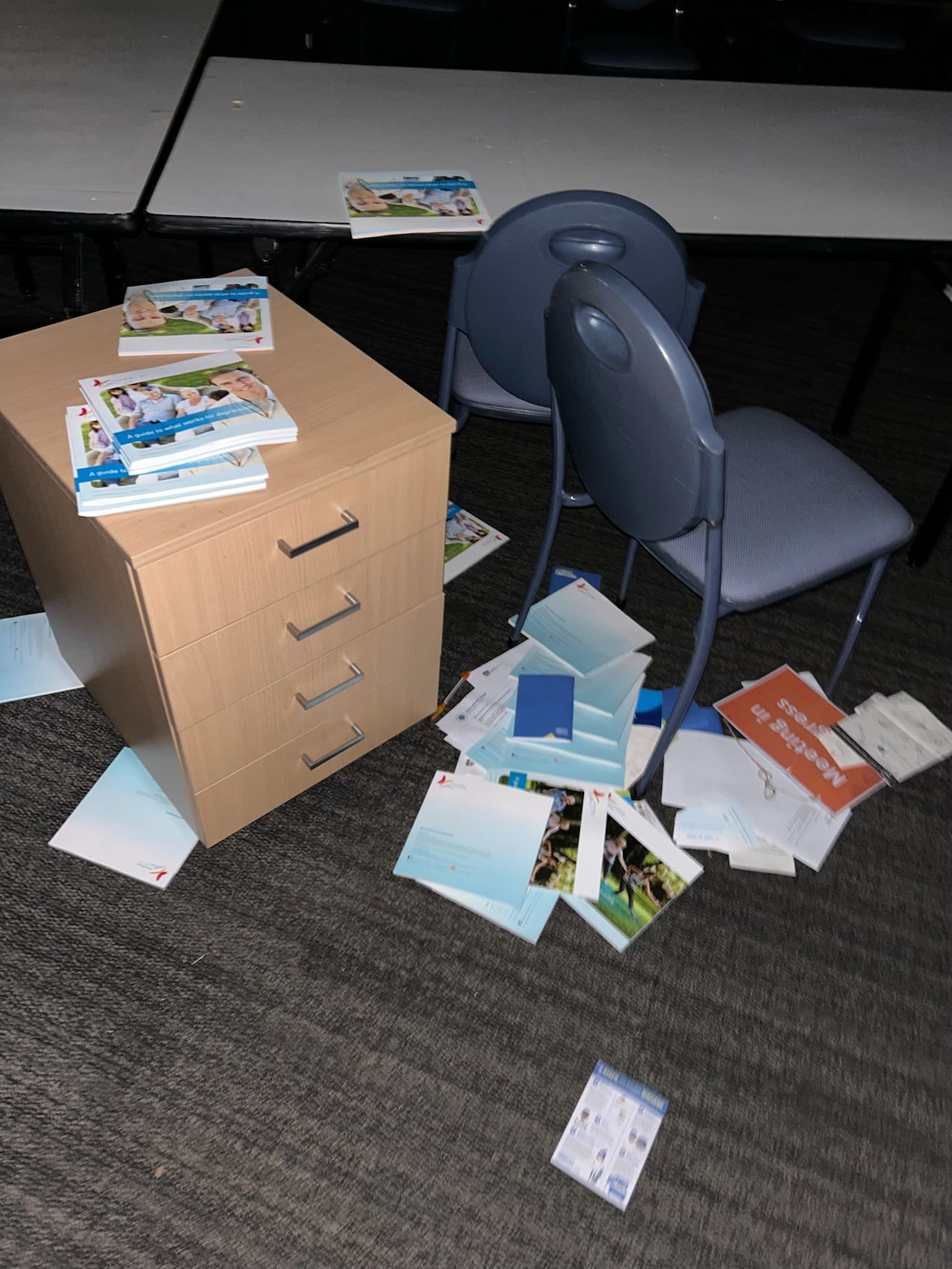

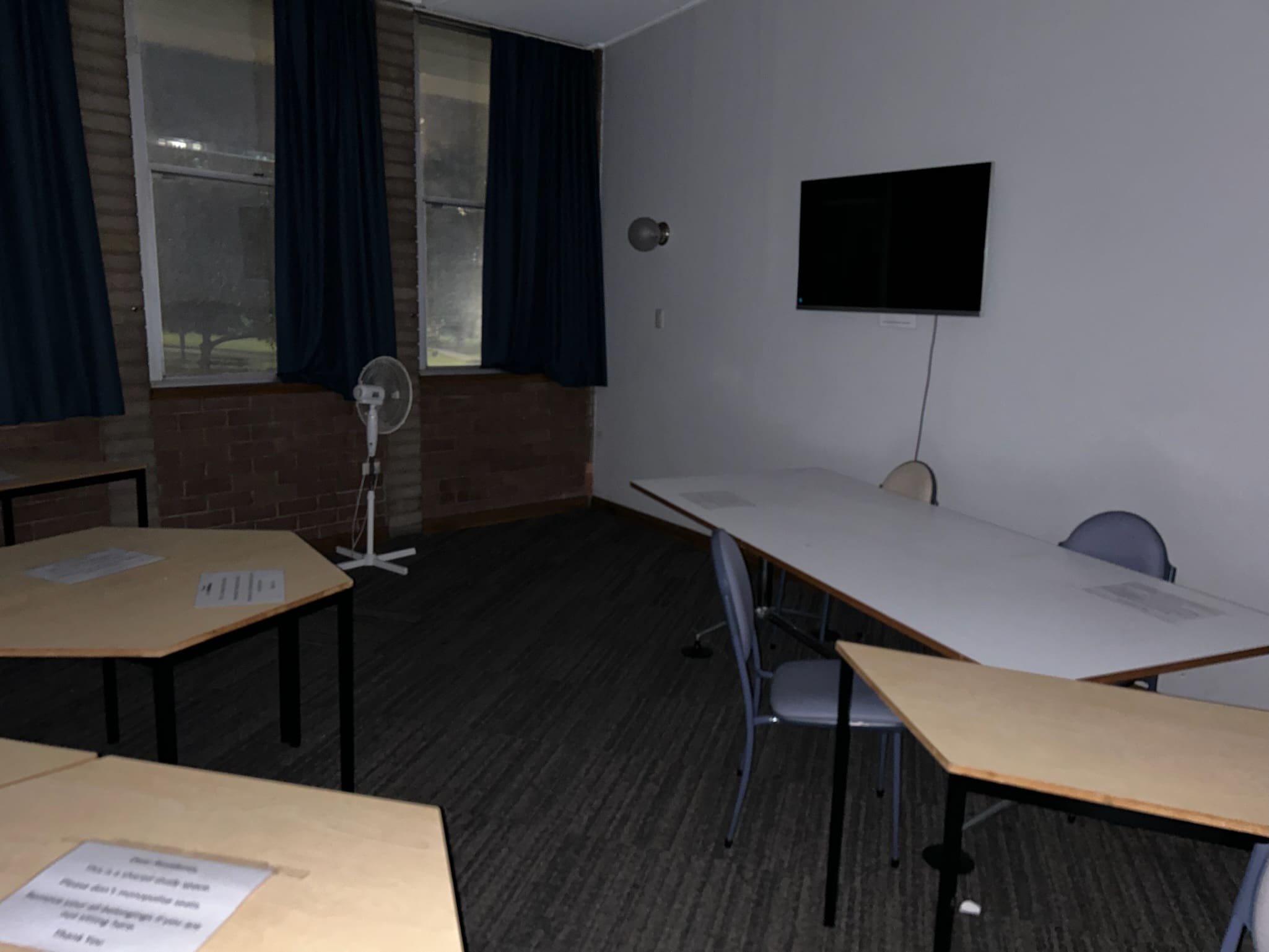

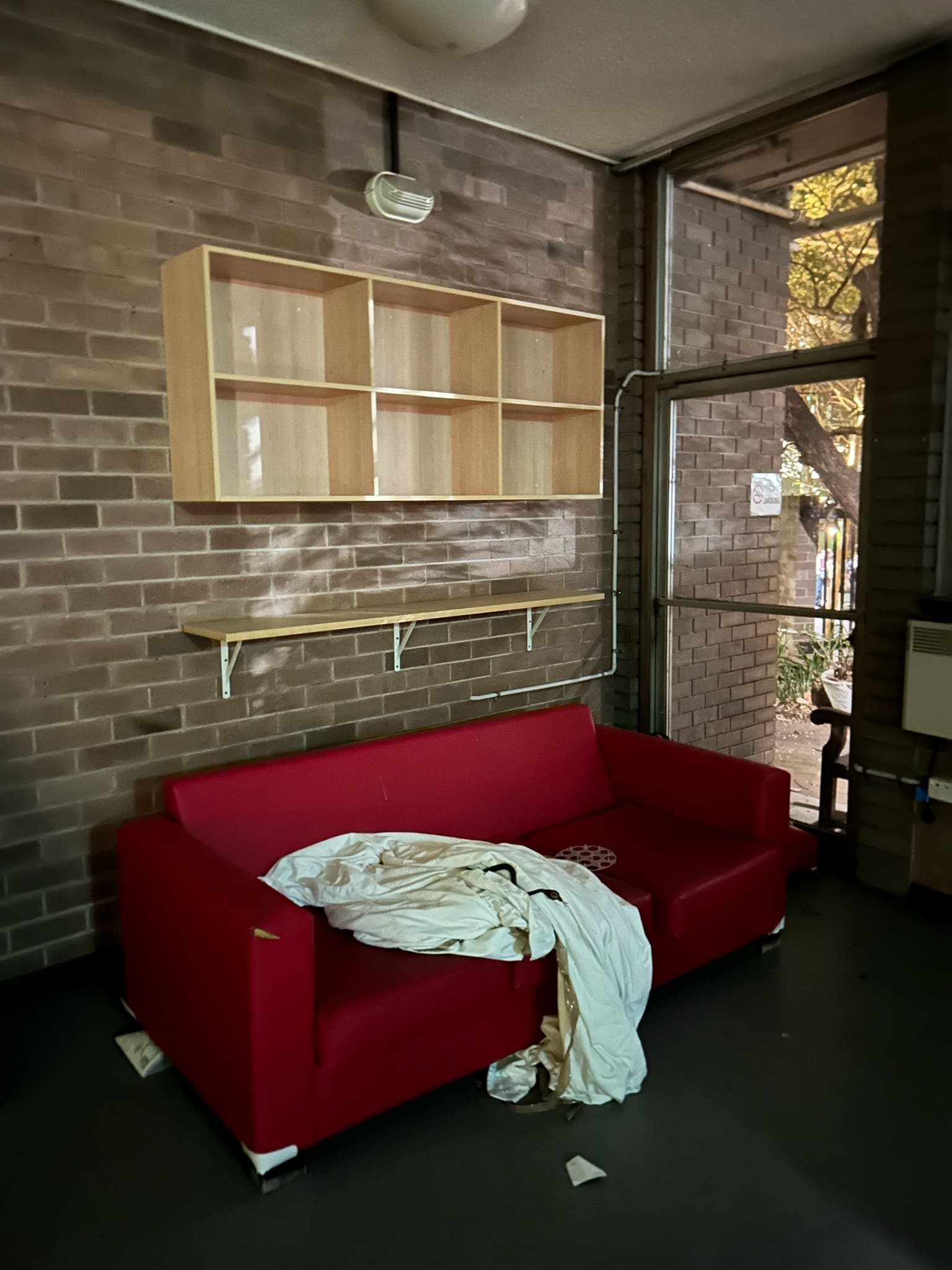

It is eerie to wander down the halls and duck into the empty rooms. International House does not feel abandoned, it feels frozen in time. If you were to sneak in tonight, you’d find that almost everything is still in its place. The bins are still lined with plastic bags. The shelves are filled with books. The plates and mugs haven’t been washed, and the pool table is still mid-game. It’s a snapshot of student life, suspended in amber. A relic from a time when the University valued the student experience over surplus dollars.

Lit corridors of International House

What makes International House feel most alive is what has been left behind by its former residents. They live on through unwiped whiteboards filled with study notes, half-baked doodles, and warnings like “don’t take law gaizzz.” Storage rooms are filled with long-forgotten personal belongings. Polaroids and printed photos lie strewn on desks — photos of dress-up parties, or gathos on the now-empty rooftop terrace. The doors of the dorms are adorned with the names of people who lived there. Jen. Rohan. Serena & Astrid. Their names lie untouched, as though the space is still theirs.

Study room whiteboard still left with notes

Dorm doors still left with residents’ name

Images strewn across desks

Storage room still filled with personal belongings left behind

The main office still had keys to every single room scattered across its tables, and boxes filled with placards of every student that had previously stayed at International House since its opening in the late 60s. Years of lives and stories left behind.

Keys scattered across the main office

A former resident commented in an interview with Honi that in the lead-up to the closure of the house, “the facilities guy was very understanding. He’s just like, if it’s not bolted down, it’s yours, you can take it. There was a lot, there was an auction, for some other items in the house, including the pool table. An Australian guy bid, I think it went for 50 dollars, and then said how difficult that would be for him to get out and move. And then, I guess if it’s still there, no one ended up taking it.”

Pool table mid game

It’s been nearly three years since International House closed its doors, and the University hasn’t touched it since then.

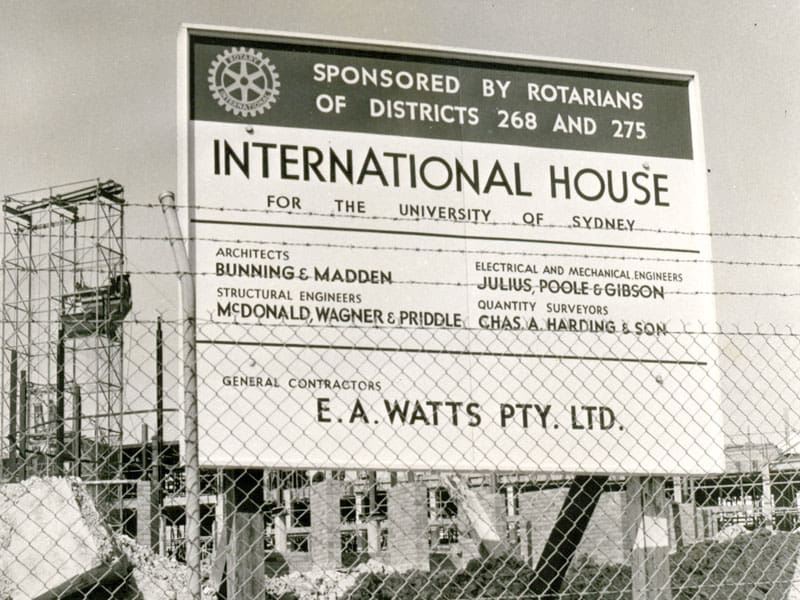

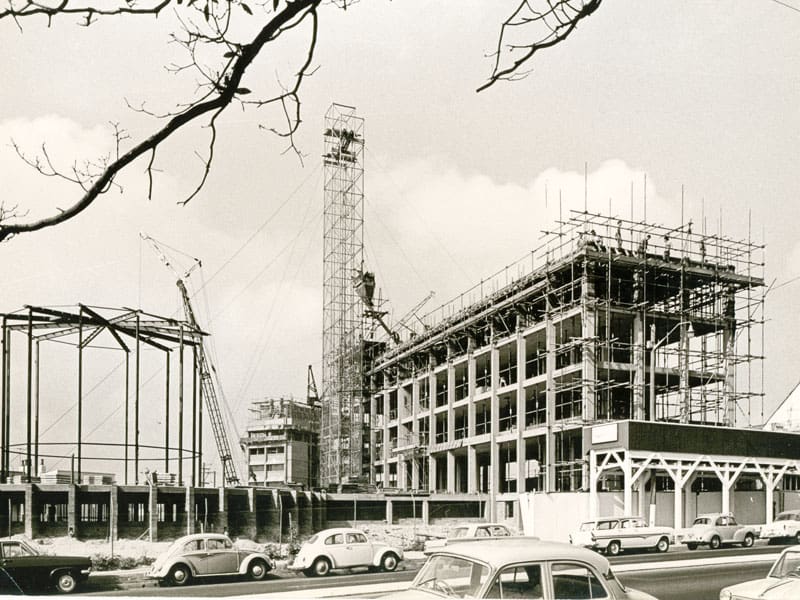

International House opened in 1967 with the aim of cultivating the concept of “global citizenship”. It was to be a space where domestic and international students could live and work together, at a time when international students represented a tiny portion of the University’s makeup. Since then, over 6000 residents have lived in the House, representing more than 100 nationalities. For many, it provided an opportunity to live on campus and meet people from across the world in an environment that was markedly more appealing than the insular, privileged and misogynistic culture which still exists in the colleges.

“Compared to the other colleges, International House had a much less toxic culture… You got a lot of the perks of the colleges, but with a more diverse group of people who were also held to a higher behavioural standard,” a former resident said.

“As a student it was formative, and it was a brilliant experience. It just exposed me to this very diverse community of people from all over the world,” another resident said.

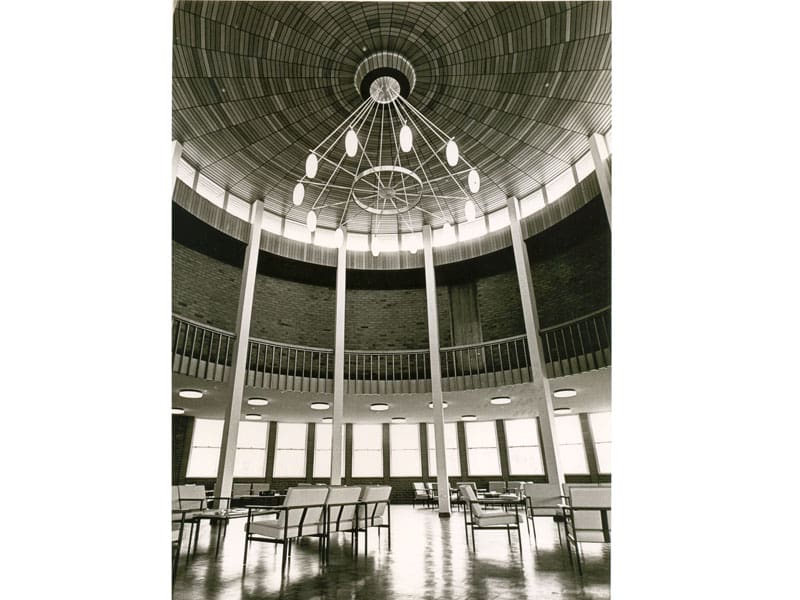

The most recognisable feature of International House is the rotunda, an iconic example of modernist architecture. Including the ground-floor dining room, the rotunda is three storeys high (and echoes tremendously, so tread lightly). Now gathering dust and piled high with armchairs and folding tables, its common area — the Wool Room — was where parties, balls and the annual International Night was held. Part of the reason why International House was so beloved by its residents was because the architecture embodied community — with common rooms, and the dining hall, naturally encouraging relationships to grow and friendships to be formed.

The Rotunda

“We had a lot of cultural festivals… we had a night where everyone would cook food from their country,” a resident said. “We’d all come down and be able to share in each other’s culture and different foods.”

There’s an untouched gym on the second level where dumbbells lie beside yoga mats and medicine balls. A large dipping bar stands up against the wall in pristine condition.

“The gym was only set up in 2018-19. Before that, it just used to be a dance room, where people would go to dance.”

Gym equipment left behind

From the rotunda’s second-floor mezzanine, a door leads to a computer lab and a communal library that houses hundreds of books on shelves and in piles on desks. The kitchen also remains fully stocked with dining and cookware. The commercial kitchen equipment is still functional and, outside in the dining room, plates and cutlery are laid out, ready to welcome a new cohort of residents that will never arrive.

Library filled with books

Meal plan left behind on the kitchen whiteboard

Industrial kitchen

Plates and cutlery fully stocked in the kitchen

“Even the simple memories are great. I didn’t sleep the night before my first day of uni, because we all ended up having a dinner, playing table tennis and trying to get to know each other, and it was suddenly 5:30 in the morning and I had an 8am maths lecture,” was what another former resident described.

“I don’t regret it. I was really tired during the lecture, but it was a very reflective start to the great community, the people I’d met, and the good memories.”

“I had very fond memories of it, and I continue to this day to be in touch with people that we knew who were other residents in the International House,” another said.

A former resident explained that, after being moved out of International House, many of the previous tenants ended up in more expensive and poor-quality housing, or were priced out of the Inner West and faced a lengthy commute to campus.

Another former resident noted “there are probably 200 students who are living in a much worse situation than International House”. Earlier this year, Honi wrote on the housing crisis — finding that many students were at risk of homelessness, or living in houses that posed a risk to their health. International students are on the frontline of this crisis, after the University enforced a return to campus this year. And yet, International House remains empty and underutilised — inhabited only by dust, detritus, and forgotten memories.

Across the country — but particularly in NSW — students, renters and low-income earners are facing a housing crisis. As debate and policymaking focuses almost entirely on the issue of supply for home ownership, public discourse largely ignores the reality that affordable student housing is failing to meet rising demand. As COVID-19 restrictions ease and enrolments for those on student visas return to pre-pandemic levels, the University has failed to accommodate for this growing disparity. In September this year, the Student Accomodation Council noted that the current crisis has “reached a critical stage” with the need to increase dedicated student housing for both domestic and international students.

Students at the University of Sydney have to fight for the limited affordable accommodation available on campus, or else resort to paying the exorbitant amounts charged by either on-campus or external providers that provide shoebox living arrangements and lacklustre student experience. And yet, International House — containing almost 200 desperately needed beds for students — remains empty, just a short walk from campus.

Along with International House, a log cabin in the Belanglo State Forest still stands, built by residents and alumni in 1977 and is under ownership by its alumni association. The state of its maintenance is currently unknown. The last public update was provided in a Facebook post from August 2020 by the Sydney University International House Alumni Association, which explained that “the University recently cleared the vegetation that grew around the cabin and cleaned the insides, so no rubbish is left to invite animals to visit. If the primary purpose of the cabin is to give international students ‘a taste’ of the Australian bush, there was discussion of whether other University facilities would be better suited for this goal, such as the Arthursleigh facility just outside Marulan.”

The cabin held a lot of “good times,” as recounted by a former resident, from firewood chopping to stargazing, and provided “a good introduction for a lot of international students to the Australian bush.” Perhaps a sneak-in to the log cabin in Belanglo is due soon.

Although no visible signs of extreme disintegration at International House were observed (beyond missing ceiling tiles) a former resident explained that “the fabric of the building was not in good shape.” All former residents interviewed noted the faultiness of the elevator. Usually out of order, the faulty elevator was responsible for “the remaining [60] residents” being “moved down to the lower floors” just a year before International House was closed.

The building’s drainage system also had issues, at one point being in “such bad shape that they decided that they would hang a drain from the ceiling along the corridor outside the food collection area.” Additionally, the height of the railings in the stairways are no longer “in conformance with the fire regulation and health and safety guidelines.”

However, despite these internal structural issues, residents noted that they had never felt as though this accommodation was unsafe or falling apart — the same cannot be said for the now-disused Darlington Terraces or Darlington House. A former International House resident commented, “there were always sort of leaks on one side of the building […] but the house in general is built like a tank.

“I remember when they were going to close it and decant us into Regiment, they were talking about the fire safety of the building not being up to code, and we were all looking at that a bit curiously, because they retrofitted the building to have hydrants on every floor, all of the doors were fire doors.

“It was all brick, and we were thinking, if the colleges that are like 200 years old with wooden staircases can pass fire inspection, it’s kind of incredulous that International House wouldn’t. The building was never flashy, people would prefer dual flush toilets or something like that, but there was never any real feeling that the building wasn’t stable at all.”

An internal map of International House in the stairwells

The issues that recur in conversations with former residents have been sustained over years of operation, although the COVID-19 pandemic seemed to have given the University an open licence to shut down a building of historic value and significance.

Although International House had established councils and alumni associations, it did not “really have any financial autonomy”. Instead, it was treated as a “unit of the University in such a way that there wasn’t a possibility of really putting a large amount of money aside, unless it was approved by the University.

“The University was not in favour of pouring a lot of money into a building that they considered to be past its use-by-date.”

Despite the demonstrable value that International House brought to many students, it’s clear that the University values profit above all else. When the Queen Mary Building provides 800 beds, and International House has a capacity of 200, the University deprioritises the latter accommodation. However, the University fails to take into consideration the formative experiences that many alumni have recounted — experiences that cannot be replicated at any other accommodation provided on campus.

The communal value provided by International House has not been prioritised in other accommodation provided by the University, instead deepening divisions between students — particularly between international and domestic students. A former resident highlighted that “especially going back to uni at the moment and seeing that there’s a big sort of divide between a lot of international students and domestic students, it does definitely feel like something pretty substantial was lost.”

A spokesperson for the University commented that “our priority is to ensure that any accommodation we provide to our students is safe to occupy. We’re still in discussions with International House about options for the building and site and continue to provide regular updates to International House alumni.”

In terms of the increasing inaccessibility of student housing, the University claimed that “we provide a range of support and advice to help our students find affordable housing options on- and off-campus, including providing emergency accommodation and financial assistance if needed.” While the redevelopment of International House is continually delayed, the University has proceeded in selling off over $70 million in property — including student accommodation — and increasing rental rates across its housing by 6% on both the Camperdown-Darlington campus, and the Camden campus next year.

For now, International House remains frozen in time — a reminder of a different world, one where the University of Sydney had different priorities. You leave feeling as though you’ve consumed years’ worth of memories and experiences etched into the fabric of the building. A sense of uncertainty and fear follows you out the door — the sense of losing a structure that provided such value and worth for students, a feeling that your University experience cannot match up to what once was, and the exhausted anticipation of another long trip back to your mouldy, overpriced apartment.

More images of International House currently:

International House through the years. Images provided by a former resident.