A historic building owned by the University of Sydney has been sold for $16.5 million today after a successful bid by a private developer. A bidding war saw prices escalate from $9 to $16.5 million in just over ten minutes.

Formerly home to the University’s Psychology Clinic, which offers student-led psychological assessment, therapy, and psychometric testing under the flagship Brain & Mind Centre, the Mackie Building was acquired by USyd in 1955.

Mackie is located just across Footbridge close to both the University and public transport to the city centre. The building boasts 64 rooms spread across two levels around an outdoor internal courtyard.

When purchased, it had a single floor until the University added a second level to house the burgeoning needs of various departments.

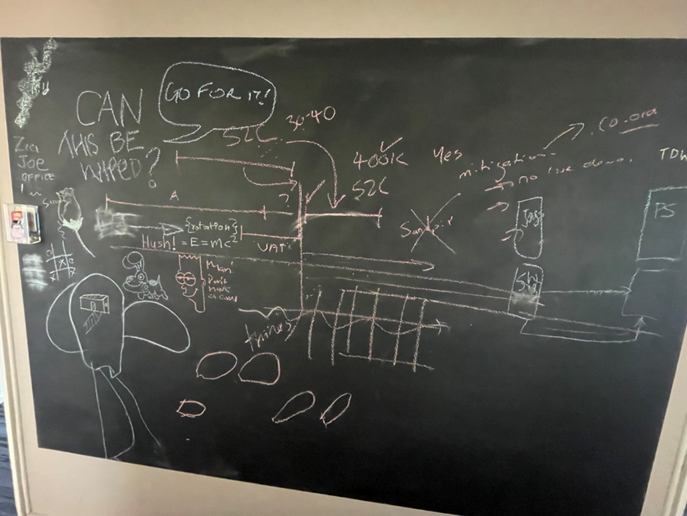

When inspected by Honi Soit as part of the auction, signs warning of water damage were plastered across the ground floor. Going deeper inside, academics’ door signs remained intact, including a communal blackboard still etched with students’ doodles.

In 2018, Honi reported that the University earmarked the building as a potential site to develop new student housing in recognition of an acute shortage of affordable student beds.

BresicWhitney representative Shannon Whitney said that there were five registered buyers for Mackie and that most of the buyers were “interested in student housing”.

City of Sydney Councillor Sylvie Ellsmore (Greens) told Honi that she and several other councillors voted against the University’s rezoning proposal in late 2023. The proposal meant that the Mackie Building could be used for commercial purposes rather than purely educational. It is understood that the majority, including the Lord Mayor Clover Moore and her team, backed the proposal.

The development follows an Honi investigation which found that the University is considering selling the Darlington Terraces — formerly home to more than 200 students and commanded some of the lowest rents on campus — for approximately $78 million.

Before being mothballed, the Mackie Building was deeply embedded in the University’s cultural life, specifically, with its history of Indigenous education.

Established to train Indigenous teaching assistants, the early program offered qualifications spread across three levels that culminated in an equivalence of NSW’s High School Certificate (HSC) recognised by the University. Promptly opening in 1975, the program started with just twenty women and two men under the tutelage of the late Professor Alan Duncan — a passionate academic who was also pivotal in the founding of the Aboriginal Education Council (AEC).

In this background, I decided to chat with the Australian Catholic University’s Emeritus Professor and Wandandian person Janet Mooney, a co-author of Taking Our Place: Aboriginal Education and the story of the Koori Centre at the University of Sydney (2010) to uncover the building’s relationship with the groundbreaking Aboriginal Teachers’ Assistant Program (ATAP).

Mooney entered the ATAP in 1990, some sixteen years after the program was first inaugurated at the University in 1974. She taught Counselling at the ATAP and then became Director of the old Koori Centre until its closure in 2014.

“Alan Duncan tried to get a primary teaching course but the University of Sydney and the Faculty of Education wouldn’t have a bit of it so that went to Western Sydney,” she says.

However, one source of constant tension between the fledgling program and the University was that the certificates “were not actually part of the Faculty of Education”. Graduation ceremonies were conducted separately from USyd graduates at Manning House because they were not recognised as “academic”.

At the time of the program’s founding, Indigenous education was in dire straits. In 1976, NSW employed just four First Nations teachers while there were more than 10,000 Indigenous students across the state.

Another source of significant grievances was the School’s constant financial difficulties. In the 1970s through the 1990s, the program dangled between hope and austerity as the Commonwealth and NSW government engaged in acrimonious arguments over funding as the agreement meant that the University was not responsible for funding.

“We didn’t always know if we could run the next year. You had to acquit the money that got from the Commonwealth and they were very nitpicky. It’s really ridiculous some of the stuff they used to ask so it was very precarious,” Mooney explained.

According to Taking Our Place, initial federal government funding amounted to just $26,000 in 1975. No money was allocated in 1976-77 for salaries in the Commonwealth’s estimates at all and the state had to take on the task.

When the 1980s took a turn, the teachers’ aides were subjected to “miserable pay and conditions”, paid just $4.85 – $5.44 per hour until a successful complaint to the NSW Anti-Discrimination Board paved the way for better remuneration.

All of this was exacerbated by the fact that most students were mature-aged and had young children of their own yet received no childcare allowances.

Despite all of this, the program went on to graduate hundreds of students by 1983 and even went on to make an impact beyond NSW and eventually secured the green light from USyd to evolve the program into a Bachelor of Education in its own right. This paved the way for the old Koori Centre itself, regarded as offering some of “the best” units of study by Aboriginal higher education.

“After many years of working hard, we were actually able to get into the main university and get the [Bachelor of Education] up and it was amazing to see because a lot of the TAs from the ATA program came back and became teachers,” says Mooney, evidently proud of the program.

Yet life in Mackie itself was not always idyllic, given that the ATAP and the Aboriginal Education Centre could not expand. Assigned just two teaching rooms: a small lecture theatre and a single tutorial space, Mackie seems to mirror the endless financial troubles ATAP and Aboriginal Education Centre (AEC) faced and thus, came to be viewed as an obstacle.

The Koori Centre eventually moved into the main university at the New Education Building where it remained until 2013 when it was abruptly closed shortly after former Vice-Chancellor Michael Spence took office.

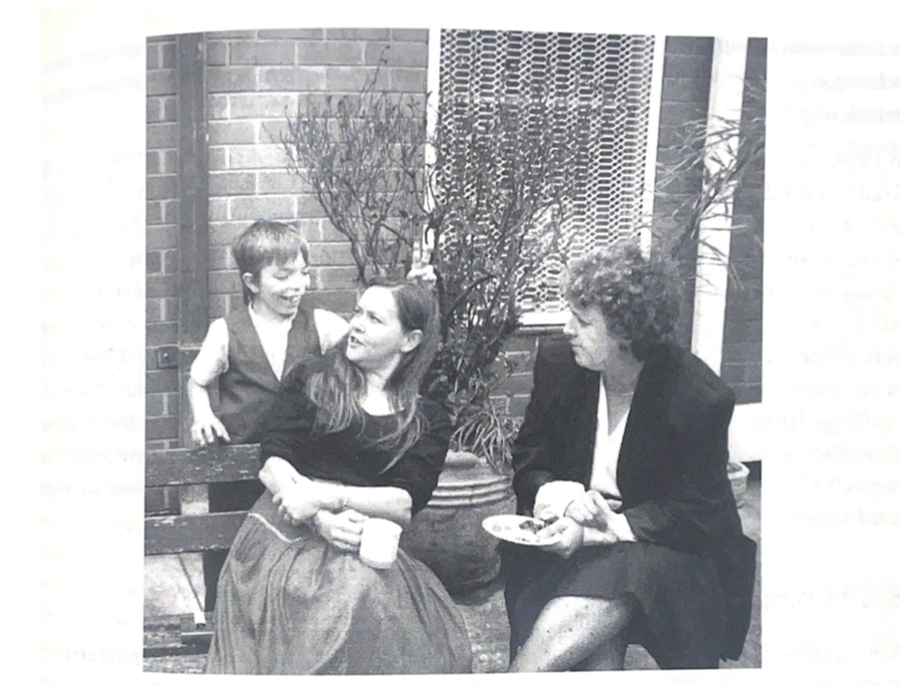

And so, in many ways, the Mackie Building represented a microcosm of the vicissitudes that Indigenous education had to navigate. Mooney recalled a conversation with an acquaintance who reminisced on their time back in Mackie’s weekly student and staff barbecues.

“He said: ‘I just hated it!’ because I [the acquaintance] could smell this beautiful barbecue and I wasn’t invited. So it was a very family oriented building,” says Mooney with a chuckle.

“You know, it was a good place to work. We had lots of fun there and then the isolation was sort of a special place for us.”