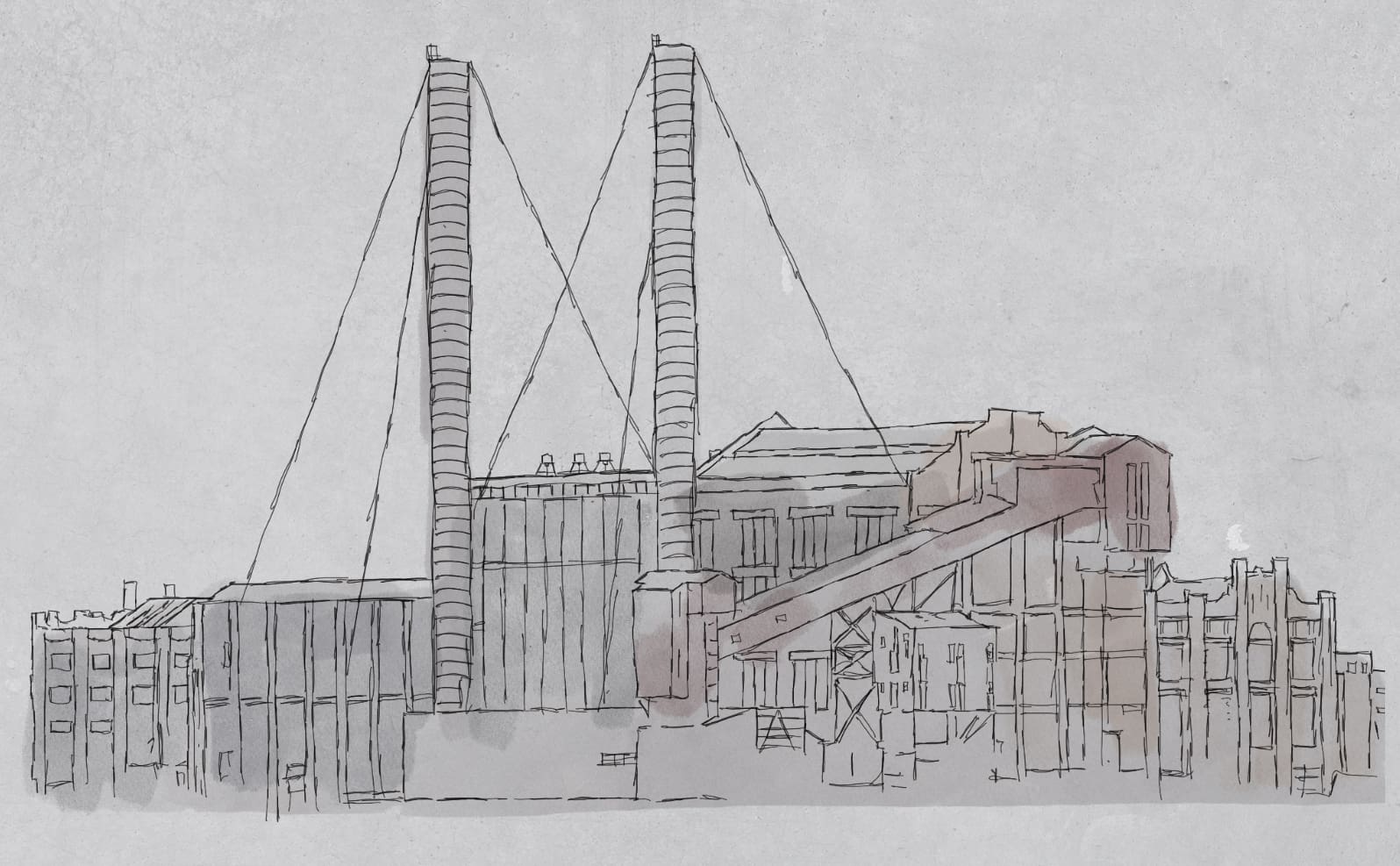

Curving off the Anzac Bridge into Rozelle, you’ll notice Rozelle Bay to your left and a towering disused power station to your right. It has two sentry smokestacks which oversee the industrial waterfront. Just down the road, the Westconnex Rozelle Interchange has transformed an area near the bay over the last few years. Like nothing else, the White Bay Power Station welcomes you into the once-industrial Inner West from the bustling city centre from which it is only separated by Pyrmont and the twice-intervening harbour.

The power station’s tumultuous story is an allegory for the ever-changing Inner West, showing how much is to be found in the investigation of local history, and how local areas have their own unique roles in the broader developments of society at any given time.

In 1912, Sydney’s tramways and railways were growing rapidly. The tram network was extensive — it would become the largest in the Commonwealth outside London and the largest in the Southern Hemisphere — and greater power capacity was needed to fuel its expansion. That year, the New South Wales Government Railways, a predecessor to Sydney Trains and NSW TrainLink, would begin work on the plant, which is constructed in the Federation Anglo-Dutch style. A now-defunct railway branch line was built to serve it later on.

Rozelle, located 3 km from the city centre, was a working class suburb at the time, as were those around it. It had only received a name twenty years prior, drawn from the “Rose Hill parrots” (Rosellas) — Rose Hill being the short-lived colonial name for Parramatta, not to be confused with the suburb now named Rosehill. The suburb was previously part of neighbouring Balmain. The Metropolitan Goods Railway to Darling Harbour was opened in 1922, with a goods yard subsequently constructed in the suburb.

A 1930s photograph shows a bustling facility boasting nearly two dozen chimneys, with the working-class townhouses of Rozelle visible behind it and the masts of ships in front of it. This was the Inner West in all its grit, soot, and industry — the railways, the tramways, power generation, and the working harbour intertwined.

White Bay’s furnaces would continue burning away until Christmas in 1983. The nineties would see decontamination of the site, asbestos removal and the removal of most of what machinery had remained, as well as a heritage listing in 1999. With the goods line decommissioned in 2009 and converted to light rail while the disused rail yard became overgrown, the derelict power station served to remind a gentrified suburb of its past.

As was once the case with many now-cherished historic buildings, such as the Queen Victoria Building, the defunct White Bay Power Station wasn’t universally appreciated. It was considered for use in 2016 by major tech companies including Google, though nothing eventuated. In November 2020, then-Treasurer Dominic Perrottet savaged the building.

“Shocking building, it should be knocked down like the Sirius Building,” Perrottet remarked.

By the following week, his stance had moderated. “Perhaps I was too hasty when I suggested the old White Bay power station should be demolished. This week, I visited the site with Inner West mayor Darcy Byrne and my colleague Planning Minister Rob Stokes, whose transcendent wisdom and insight bestowed upon me, mere mortal, a fuller understanding of its historical significance,” Perrottet wrote in The Sydney Morning Herald.

Now, the White Bay Power Station has received a new lease of life. The maligned colossus standing guard at the gates of Rozelle will become an arts venue, opening to the public in March for the 24th Biennale of Sydney. With its boilers and a large steam turbine remaining in place, Arts Minister John Graham compares White Bay favourably to London’s repurposed Battersea Power Station, and even more so to the Tate Modern which he notes entirely lacks such machinery. I cannot think of a more fitting, more dynamic use for the old battler. One can expect that The Bays Metro station, proposed for opening in 2030 as part of Sydney Metro West, will draw many to the site.

Imagine if Perrottet’s mind had not been changed. In the same world, other historic charms would also certainly have been lost; not far from the power station, the Rozelle Tram Depot sits beside Jubilee Park. This building was once run down, but was renovated and turned into a beautiful shopping centre featuring an old Sydney tram inside. The buildings of Callan Park, including the domineering clocktower on the site, sit on the other side of Rozelle. The Iron Cove Bridge. The Bridge Hotel. Local heritage is everywhere.

Let’s do our best to appreciate it, for it gives our communities a unique sense of identity and character.