TW and CW: This article contains mention of death, graphic violence, torture, sexual assault and rape, and coarse language.

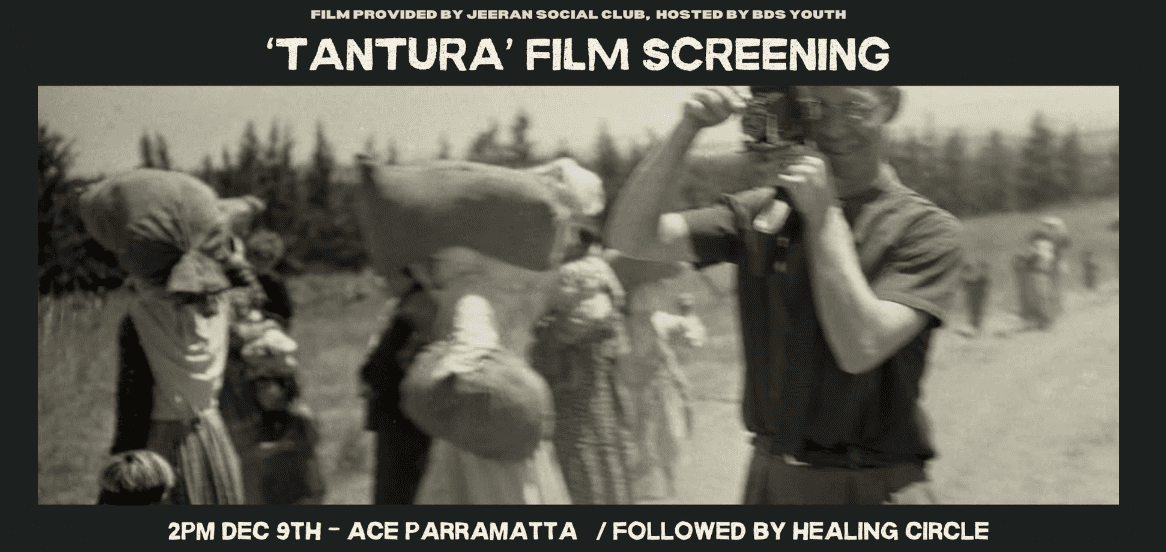

On Saturday December 9, BDS Youth Australia and Jeeran Social Club hosted a screening of the 2022 documentary Tantura, directed by Alon Schwarz.

Tantura was a Palestinian village in the south of Haifa. It was considered a relatively wealthy area with a fishing and agriculture-based economy, and a population of approximately 1500 Palestinians. It is now known by the name of Kibbutz Nahsholim and is the site of recreational facilities.

When you google “Nahsholim”, the links are of websites promoting the Nahsholim Seaside Resort, Holiday Hotels and Kibbutz tours. In contrast, when you google “Tantura”, the massacre dominates the search results pages.

Between May 22 and 23, 1948, it is estimated that a figure anywhere between 150-280 Palestinians were killed in Tantura, being buried in mass graves after the ‘War of Independence’ ended.

The documentary frames this massacre within the context of the 1947 UN Partition Plan of Palestine and the conflictual framing of 1948 as a War of Independence to Israelis and a Catastrophe (Nakba) to Palestinians.

It is important to note here, that Palestinians were not actively centred in the documentary. In the dialogue between interviewee and camera, they were relegated to the role of silent victim, with their faces visible in footage of 1948 events.

Most of the interviewees were veterans of the Alexandroni Brigade of the Israel Defense Forces — who captured Tantura and later formed the Kibbutz — in addition to a few Palestinians speaking to what they witnessed.

Teddy Katz is the focus subject due to the events that transpired after he published his Master’s thesis in 1998. He conducted two years worth of interviews with both “Arabs and Jews”, compiling over 140 hours of tapes, affirming that the Tantura massacre had indeed occurred.

Once a Ma’ariv journalist discovered the paper, the discussion was moved beyond the academic space and into Israeli society, where controversy ensued. Those who were interviewed by Katz and had admitted to the massacre, later denied it, and brought forth a defamation trial against Katz. This was the first legal case to deal with the Nakba.

Katz told Schwarz in the documentary, “if you want to make a movie about [Tantura], you will be hunted down like me.”

His university degree and teaching post were revoked and his work removed from shelves before his eventual ostracisation from Israeli society. This was the price to pay for challenging the formal national memory.

Katz did sign an apology letter retracting his claims, but later attempted to withdraw his apology and resume the trial. The judge overseeing the trial — also interviewed in the documentary — refused.

During the documentary, the judge listened to Katz’s tapes for the first time as they were never heard in court. She responded, “if it’s true, it’s a shame”, and as her dog writhed next to her, she said “calm down, it happened a long time ago”.

Many heinous details of the Nakba were described to Schwarz, including the torture of Palestinian prisoners, genital mutilation, murder within enclosures of barbed wire, looting of homes, use of flamethrowers and grenades, and rape allegations. Many more details were withheld, with one man saying he is “forbidden to tell more.”

According to Alessandra Tanesini’s 2018 chapter, ‘Collective Amnesia and Epistemic Injustice’ within Socially Extended Epistemology, collective amnesia is often imposed by the most powerful within a group, and they shape the conversation by deliberately or involuntarily obfuscating and rejecting memories that are deemed incongruent to their self-identity.

It remains stigmatised in Israeli society not only to address Tantura, but the wider repercussions of the Nakba, as it threatens the core beliefs surrounding the formation of the state of Israel.

The documentary referred to the release of IDF archives in 1988 as an example where censorship was enacted. Material that could harm the military’s image, including behaviour that is devoid of moral standards, was withheld from public access.

It was New Israeli historians, including Ilan Pappé, who used their access to official archives to uncover evidence that challenges Nakba denialism. These historians questioned Israel’s historical narrative which views the declaration of a Jewish state as having been achieved through victory in a war against Arabs who, in turn, willingly fled.

The historians who were interviewed confirmed a tendency for societies to avoid addressing their grave pasts. They applied this line of inquiry to the creation of a nation at the expense of another population, by way of expulsion from their lands, religion, and culture.

In an interview with POV Magazine, Schwarz observed while watching the interviewees, “When somebody says, nothing happened, I see how he looks to the side. Body language is deeper than any transcript.”

Some of the Alexandroni Brigade members refused to refer to their actions as killing, as others claimed the killing “happened here and there” and that they were 17 or 18-year-olds who “were turned into murderers”. It reiterates the long-standing belief that Arab deaths in 1948 are “casualties” and a natural by-product of a righteous war, as opposed to a systematic and orchestrated massacre of civilians.

Other veterans spoke to their internal dilemmas, lamenting, “why can’t I tell?” — whilst many said they “don’t really remember” and “I made myself forget.” The Palestinian witnesses who were interviewed stated that they “remember everything”, including recognising family members amongst the piles of bodies.

In another act of denial, one academic dismissed and laughed off the testimonies of Tantura being a massacre, due to the research being dependent upon oral testimony. He continued by stating, “I don’t believe witnesses.”

Schwarz cited the IDF archive itself, use of aerial photography, and historical maps as well as documentation pertaining to the Department of Arab Affairs, to back up Katz’s claims, proving the legitimacy and grave reality of the massacre of Palestinians in Tantura.

In ‘A Case against the Argument from “Collective Amnesia” and “Forgetting”’, Melanie Altanian posits that while the terms “amnesia” and “forgetting” are useful, they indicate passivity. She found that people choose to engage in distortion, or suppression, of memory and testimony as to rehabilitate the national self-image. This is addressed in the documentary with critique pertaining to a manufactured moral superiority attributed to Israel’s army and its preservation of a “pure” status as a nation-state.

Schwarz also confronted Israel’s focus on preventing its citizens from knowing the realities of its history. As this documentary was made by Israeli filmmakers, it is primarily intended to convey to an Israeli audience that mass graves lie beneath them – more specifically, under the parking lot of Dor Beach – and how this has been concealed. Schwarz’s interspersing imagery of a young girl digging in the sand of the beach needed no explanation.

These mass graves were confirmed by geographical experts to take the form of a trench, and have been opened at least once. One interviewee attested to having seen the bones himself, and was told that they are “from the days of Napoleon Bonaparte”.

At one point, there was a discussion between two women over whether a memorialisation or monument is needed for recognition. One argument being put forth was in favour of adopting a similar model to Australia’s recognition of Aboriginal people as First Nations. However, the other argument was that “Tantura is history” and that “they [Palestinians] can remember quietly”.

While the documentary would have benefited from playing more of the revelations of the tapes, as well as asking interviewees further questions when they refused to talk, Schwarz presented to the audience how the suppression of memory and more importantly, oral accounts all contribute to an active project of denialism in Israel.

After the screening, a trauma-informed therapist led a healing circle. In relation to the ongoing genocide in Palestine, many attendees spoke to their heartbreak, grief, anger, helplessness, despair and frustration.

The documentary itself elicited disbelief over how individuals could freely admit to violence or deny they ever committed anything that amounted to a massacre. Furthermore, it led many attendees to remember what their ancestors experienced, and ascertain the difficulty between choosing to stay in one’s homeland or fleeing for safety.

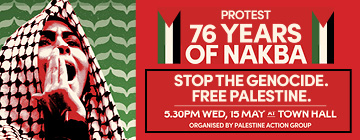

It was also determined that in such times of despair, hope can be gathered from courageous Palestinians in Gaza who continue to exist with unwavering faith. Attendees cited the increasing number of non-Palestinians who stand in solidarity, turning up to protests and are educating themselves on the 75-year history of oppression as another source of hope.

Despite being buried beneath Nahsholim, the village name ‘Tantura’ will forever hold the weight of a history that is ingrained within the memories of all those who witnessed the massacre. Whilst some have the luxury to forget – or at least attempt to – others pass it down through intergenerational trauma because they cannot, and will not, forget.