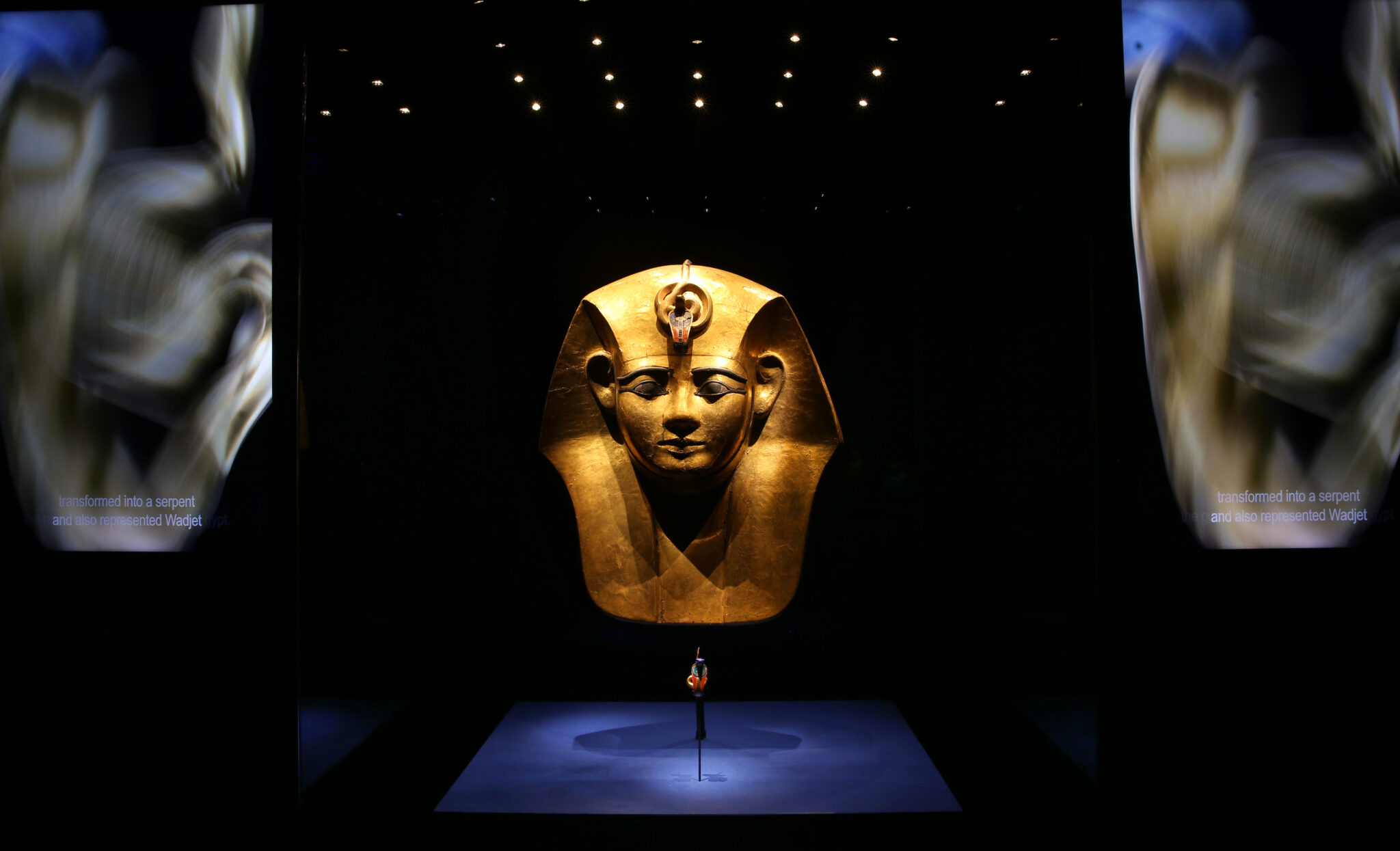

Last month, Honi Soit had the chance to speak with Fran Dorey, the Australian Museum’s Head of Exhibitions, about Ramses & the Gold of the Pharoahs, an exclusive display of antiquities straight from Egypt. Fran has been with the Australian Museum since 1996, and was heavily involved in co-ordinating the impressive feat of bringing this exhibition to Sydney. Below, Fran tells us about the process of organising this collaboration, some of Ramses’ mischievous habits, and the Australian Museum’s stance on displaying human remains.

HS: Hi Fran! Thank you so much for joining us at Honi Soit. Would you be able to run us through the process of organising a collaboration of this scale?

A few years ago, there was a Tutankhamun exhibition which was organised by an international touring agent in association with the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. We hoped to be one of the 10 venues selected worldwide and went through a rigorous submission process. We had to submit an application for such a massive undertaking, receive financial support from the NSW Government, and had to make sure that insurance could cover something of this size. Then we submitted the forms and came out on top. That process was six months to a year.

Unfortunately, after all that work, the exhibition became stuck in London due to COVID and the Egyptian Government cancelled the tour. The Ramses exhibition was created as a substitute, and because we’d already been successful they offered us this exhibition instead. This is a multi-billion dollar and very valuable exhibition, so a lot of paperwork, planning and even politics go into hosting something like this.

The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities oversee[s] all the conditions of how the objects are treated and travelled, and the ministers work closely with the museums to set everything up; most pieces come from the Grand Egyptian Museum and some other museums in Egypt. The Ministry worked with the main curator who selected the pieces and authorised them to be released.

HS: Ramses was renowned for putting his name or image on works to remodel them in his likeness. Considering that these works have been remade, whether by Ramses or historians, how do you approach these artifacts which may be in parts or reconstructed?

Ramses had a habit of wanting to spread his image. You can either start works from scratch (which he did), or you can add to what someone else has done (which he did at a lot of temples), or you can go in and say “right, I’m taking that statue and recarving it, one will be like my mother and one will be modelled to look like me”. Ramses did all three of those, and he’s not the only one in history to have done that.

This idea of remodelling, adapting or restoring is not new to archaeologists. Throughout history, archaeologists and others have gone into sites and thought “do we take the remains and reconstruct them, or just preserve as it is?” How much do you change in the process? It’s the same with museums: you get an object and think “do you try and restore it back to what it would have looked like, or do you take what you have and conserve and display it as it is?” That attitude has tended to change. Today it’s far more likely that you don’t reconstruct it. You can make a suggestion as to what it could have looked like, but you don’t add a modern interpretation to it.

HS: The Chau Chak Wing Museum on USyd campus recently announced that they would no longer display partial mummified human remains. Whilst the exhibition doesn’t feature human remains, it does have adornments which were encased in mummified human remains, as well as mummified animals. How do you navigate the ethics of displaying these?

This is quite a complex topic and museums and institutions around the world are grappling with the many issues associated with it. With regards to Egyptian human remains, today the Egyptians generally have little issue with displaying mummified human remains. If you go to Egypt, you can see the remains of pharaohs, some of which are unwrapped. We do have human remains at the Australian Museum from ancient Egypt and other cultures, and do have policies around displaying, caring for and even repatriating human remains. Different cultures view and treat their dead differently and we are predominantly led by the culture from which those remains come. In our Westpac Long Gallery, we display an Egyptian coffin containing mummified remains of a woman, who is wrapped and treated with respect. How we refer to people is important – if we know the person’s name we use it, and we prefer to move away from the word “mummy” because there are connotations with referring to the remains as an object rather than as a person.

There aren’t any human remains in the Ramses exhibition because the focus is on pharaohs and royalty. The Egyptian Government does not allow Pharoah remains to travel outside of Egypt. We have had exhibitions from Egypt and other institutions which have had human remains, and we do have [Ramses’] coffin in this exhibition. Times change, and the way we view things changes. Who knows what will happen in the next five or ten years, but it’s about knowing what visitors expect, being mindful of our responsibility, and respecting both the dead person and the culture from which they come.

HS: My last question is: what is your personal favourite part of the exhibition?

I’m an archaeologist by background — I was at Sydney Uni as well — and this exhibition has a lot of things from Tanis [now known as San Al-Hagar], especially from Pharaoh’s tombs which are really significant finds. We don’t have many things from Ramses’ tomb because it was completely ransacked in ancient times and damaged by floods and rock falls, but we can picture what his tomb would’ve been like using these objects, and it would’ve been mind-boggling. These are incredibly valuable pieces, and it’s one of the few times this material has been outside Egypt, so that part I love.

Ramses & the Gold of the Pharoahs will be on exhibition at the Australian Museum until May 19.