I am not a coffee person. For me, heaven is a chai latte: hot, fragrant, and a perfect balance of sweetness and spice. It melds the fuzzy winter atmosphere with a more complex flavour profile than hot chocolate, containing caffeine but not degrading itself to astringency. Thus, the title Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens conjures a cosy, warm environment set in the titular nursing home, Cinnamon Gardens.

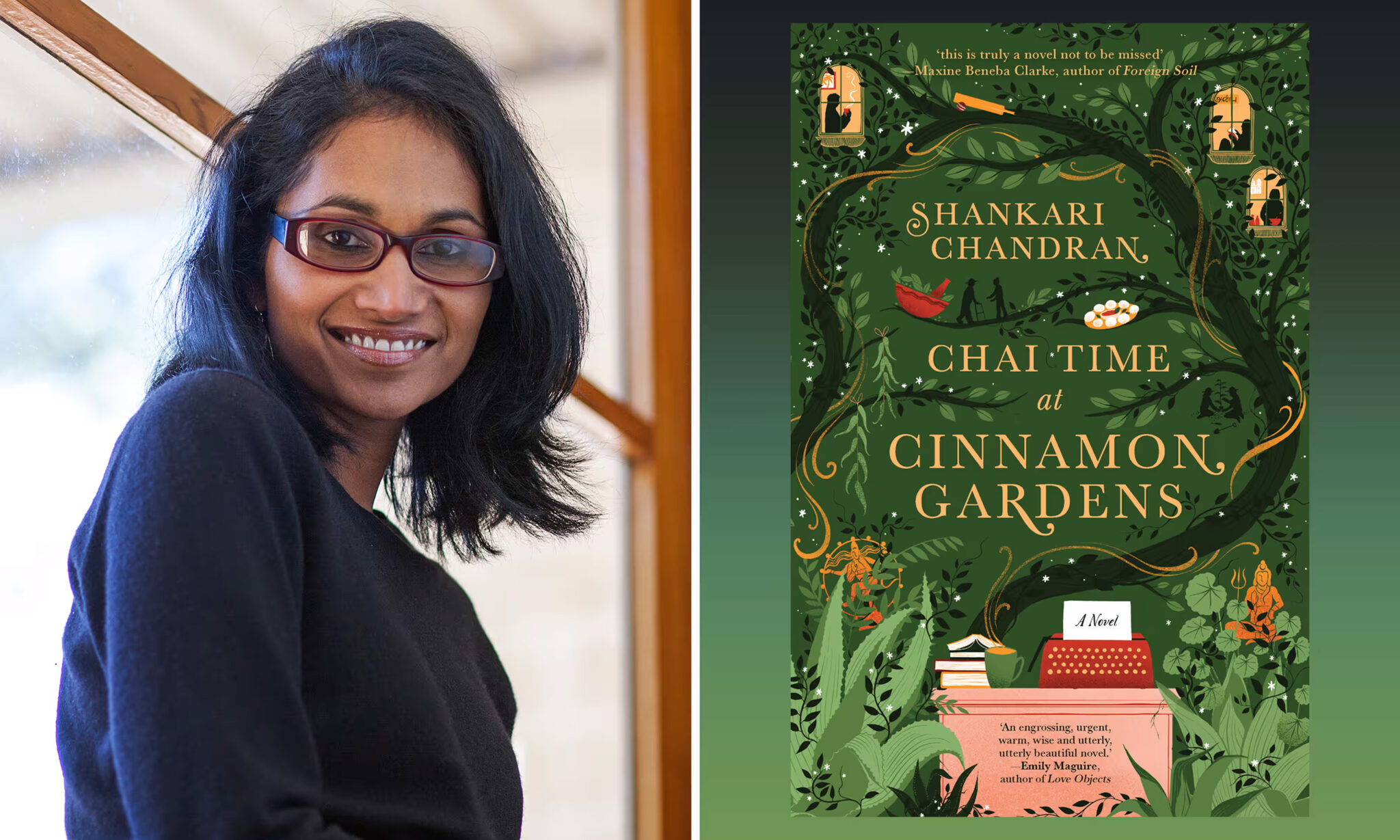

Alas! It was not to be. Shankari Chandran’s novel is superbly written, but cosy it is not. The similarly inviting cover, featuring plants, tea, books and a typewriter (I felt personally targeted) has hoodwinked many a reader into perusing the pages of this oh-so-inviting book. But the gentle beauty of Cinnamon Gardens hides the bitter and mournful experiences of those who live and work within it, who have endured hatred, racism and deep-seated intolerance.

The story weaves the residents’ past memories of their Sri Lankan homeland, , and Sydney, where racism persists and the remnants of colonialism remains in an empty plinth and the missing statue of Captain Cook.

The plot spans decades and generations, recalling the civil war in Sri Lanka and the immigrant struggle which has only recently been given the attention it deserves in the Australian publishing industry. Cinnamon Gardens was created by Maya and Zahkir in the Sydney suburb of Westgrove, in the 1980s. It acts as a refuge for themselves and other Sri Lankan immigrants from war’s atrocities. At the beginning of the book, it is revealed that Zakhir, her husband, has disappeared, presumed dead. In his absence, Maya resigns as the owner of the home and becomes a resident herself, leaving her daughter Anji and her husband Nathan to run the operation in her stead.

Many of the characters experience racism in different ways, from microaggressions to physical assaults. However,Maya manipulates the racist system to her advantage. She has literary ambitions, and sends a manuscript based on her civil war experiences to nine Sydney publishers, to no avail. Her rejections are based on her book being “too ethnic.” So Maya rebrands herself as Sarah Byrnes and writes about a straight white character called Clementine Kelly, publishing eleven bestselling books and gaining ardent devotion from the Country Women’s Association. All the shots taken at the CWA were unexpected but extremely funny. Chandran wasn’t just criticising the CWA for being overly enamoured with characters that looked like them, but at the NSW publishing industry that selectively chooses stories that might appeal to a mythicised, homogeneous Australian entity.

A prominent plotline concerned Gareth, a friend of Anji and the husband of Nikki. Nikki is Sri Lankan and works at the nursing home, so Gareth has a foot in Sri Lankan culture whilst simultaneously dealing with the bureaucratic racism perpetuated by his colleagues in the silent-but-deadly stinkfest of Australian politics. Everyone is white, nepotism abounds, and it all hits a little too close to home. The magnifying glass on Sydney politicians was just as greasy and execrable as I expected.

Another major plotline revolves around Captain Cook’s statue, which was pulled down by Anji’s father during her childhood, when he saw her and her brother casually saluting it. Her memory of this incident delivers a fascinating insight into the way that children interact with the grim and bloody side of Australian history: “CJ Cook was a criminal who was never convicted for his unspecified but heinous crimes.”

As such Anji’s defence of her father feels like a protest against the racist, colonial narratives that have dominated her life both in Sri Lanka and in this country. “In Australia, we are taught the mythology of colonisation… Captain Cook represents that mythology, that great lie that all colonisers tell themselves and the colonised. Appa said that Cook had no place in the pantheon of heroes or in our home. That’s why he took the statue down… why the statue will stay down.” Anji’s firm and defiant stance is timely and refreshing in the society that Chandran exposes, where racism is embedded within our histories, relationships and interpretations of identity.

It is at this point that the intertwining narratives of colonisation and racism in Sri Lanka and Australia converge. Chandran is doing what few Australian novelists have done; or rather, been permitted to do. Her characters face challenges similar to many Australians whose stories we do not hear. Chandran highlights how important it is to read diverse stories, as literature is a focal point through which we can see society in its simple grace and unvarnished ugliness.

The strongest points of the novel lay in its musing on identity and what it means to be Australian, even when that is undermined by racial profiling and whiteness-as-default. When Chandran engaged with these issues head-on, the ferocity and passion of her voice shone through the characters. The book sprawls over numerous characters, settings and plotlines, but it has a consistently warm-hearted spirit. The parts about the CWA and their love of the Clementine Kelly bodice-rippers were my favourite because it showed a latent racist mindset that was being blatantly duped. However, the way that Chandran deftly dealt with racism in all its shapes and sizes demonstrated palpable proof of her talent.

Racism is the novel’s main concern, stemming from the warring between Sinhalese and Tamil people, the careless disdain of bureaucrats and politicians, physical aggression from bullies on the street, and even from friends. Chandran teaches us to take heart and to forgive wrongdoings, but use stories to immortalise them in memory.