A Midsummer Night’s Dream is amongst Shakespeare’s most irreverent plays, often said to have been written for an aristocrat’s wedding. Its aristocrats are lustful and oafish, jealous and single-minded in their simplicity. The Mechanicals, a host of commoners who rehearse a performance of Pyramus and Thisbe to play before the palace wedding, are at once bombastic and full of flattery and are even greater imbeciles. The fairies live apart from man, in their forest; each can be categorised as either pettier than they are sincere, or servile.

It is upon this ground that Bell Shakespeare has crafted their latest production of Shakespeare’s bumbling triumph. Bell Shakespeare boasts a celebrated history, and their work across the country has built them a dedicated fanbase with a mind for generous donations, as a glance at the final portion of the program demonstrates. It features an essay by content agency Swash & Buckle’s Andy McLean, who highlights the depression of Shakespeare’s time and advocates for a darker reading of the play than you would often find.

In some ways this production plays into such a reading, with Max Lyandvert’s softly menacing ambient score droning underneath scenes with Oberon and Puck. There is otherwise no music. The lights in these Oberon-Puck scenes are positioned beneath the actors, gazing upwards from the stage, casting jagged shadows against the backdrop. Otherwise, the stage is lit with overhead lights. The lighting is often slightly dim.

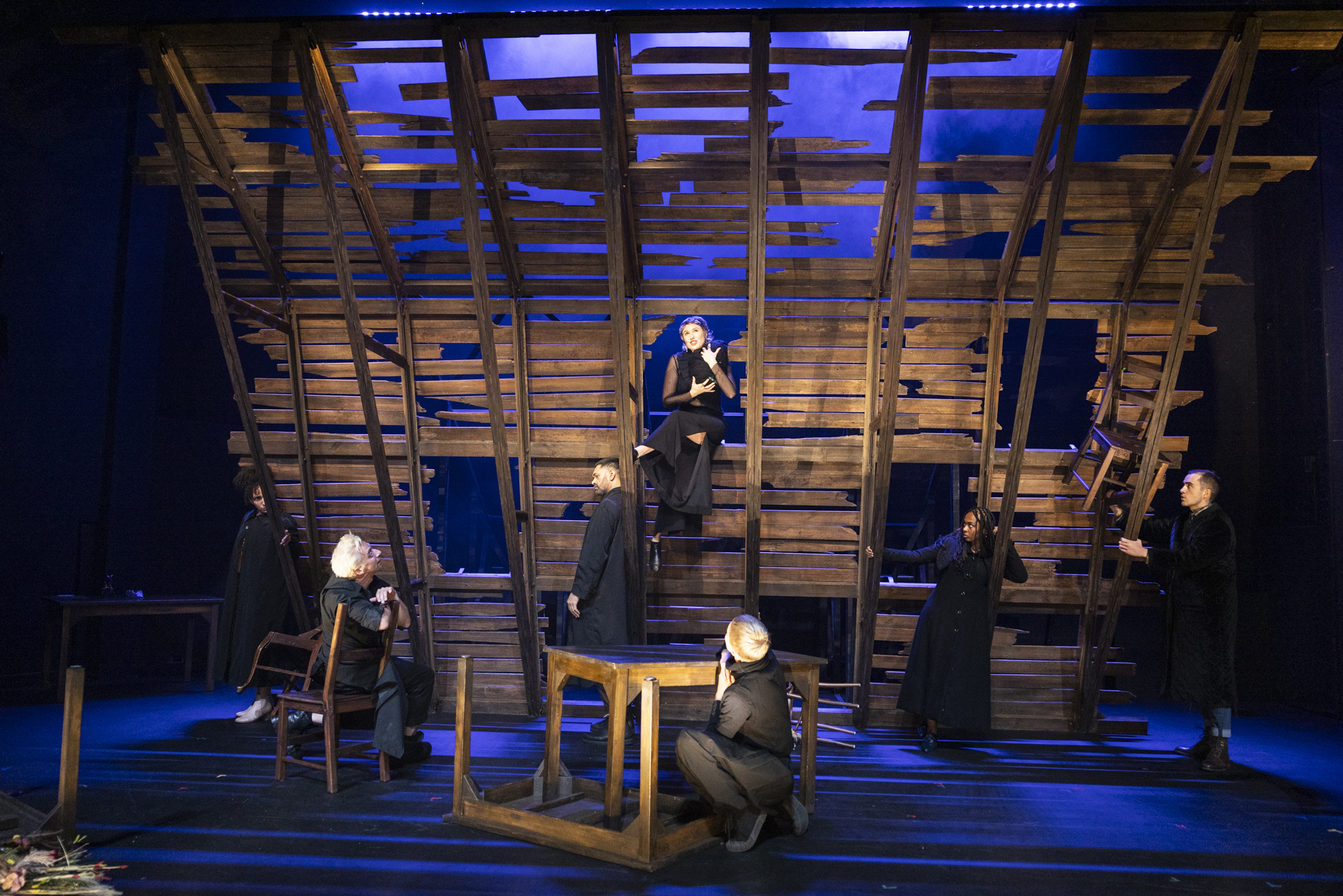

The scenes in which Theseus and Hippolyta speak to one another are almost entirely cut, most notably their wedding in Act V. That is to say, almost all of the play which features genuine love is absent. The setting is deconstructed and slightly derelict. It is a wooden wall, porous with rectangular openings, which lurches forward ever-so-slightly towards the audience, an abstraction of the forest outside Athens which is so important to the original setting of the play. That forest becoming this ramshackle structure mirrors the act of conveying Shakespeare to the modern audience which Bell Shakespeare describes as such an important part of its project.

The production is constantly moving; the actors quickly scale and orbit the wall throughout in an impressive show of agility, and it is often part of their physical comedy. Its openings become the magic of midsummer, the rift through which the fairies enter the world of man. We see this most literally in how the fairies scale the wall elegantly, passing through its higher openings, whereas the human characters crawl through its lower openings in slapstick confusion. Costume racks visibly flank the set throughout and actors can be seen taking clothes from them during scene-changes; it’s a quirky self-awareness which feels comfortable in a dream.

Where the production struggles is for newcomers to Shakespeare, despite Bell Shakespeare describing itself as ‘family-friendly.’ The set described above is all you get for the whole play, so without knowing it beforehand you wouldn’t know if the characters were inside or outside in Athens, or in the forest. The fairies are dressed in all black. The costumes only invoke the period when the aristocrats have their black coats on, which covers their outfits beneath.

That is not to disparage the costumes; they are fun, if not spectacular. Each actor, aside from Ella Prince as Puck, performs up to three characters, and each of their costumes invoke a different mood. The Mechanicals dress in a 60s sort of attire, somewhat run-down; Matu Ngaropo as Nick Bottom looks like a sailor. The aristocrats, when not in their big fur coats, dress in a more modern fashion but feel distinctly American. Mike Howlett as Demetrius dons double denim and could be mistaken for a cowboy. The fairies, as noted, wear a flowy and dramatic all-black. Towards the end of the play’s time in the forest their costuming breaks down and they wear the costumes of their aristocratic counterparts, in a welcome change.

And lastly, the most important part: the performances. Alongside Ella Prince, who is an interesting but restrained gender-non-conforming Puck, each actor plays their three roles to varying degrees of excellence. Matu Ngaropo steals the show as Bottom, with a captivating presence that caused raucous laughter from the audience in the final play-within-a-play. He is a very capable Egeus as well. Imogen Sage is the only actor with three notable roles and plays them each wonderfully. Her Titania is passionate and her Quince plays perfectly off Ngaropo’s Bottom. Her Hippolyta is discrete but gives off a distinct air of quiet discomfort to Theseus’ enthusiastic adherence to the patriarchal norms of the time.

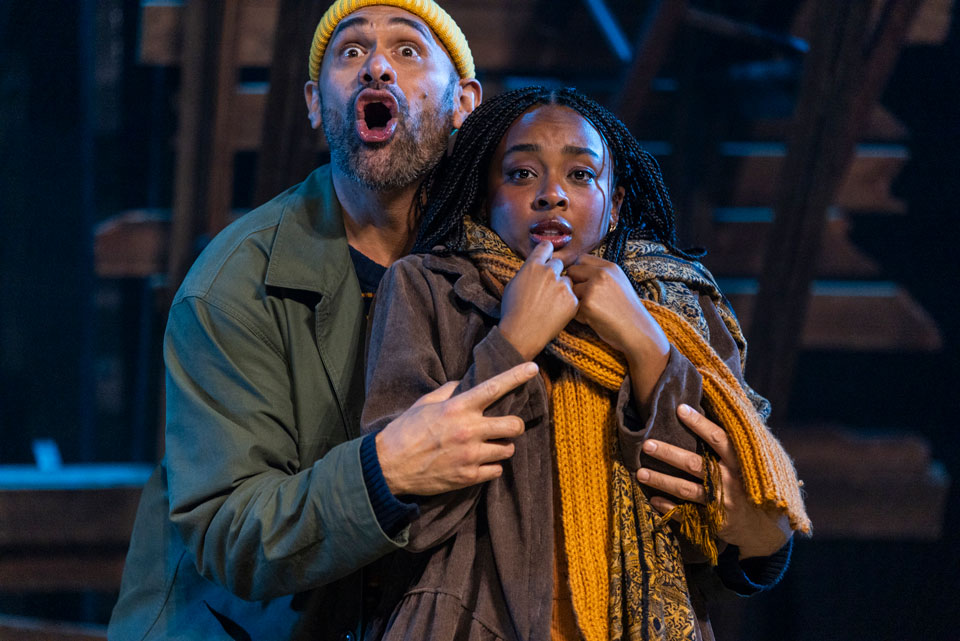

Anuhim Abebe and Isabel Burton seem like old friends as Hermia and Helena and sell their lines and slapstick routines with expertise. Laurence Young and Mike Howlett as Lysander and Demetrius do the same, playing off each other well in their fights over both Hermia and Helena, though they somewhat lack passion. Richard Pyros, finally, is supreme as both Oberon and Theseus, with the gravitas, volume, and vigilance to play such bold characters. Further, his performance as Flute in the final play-within-a-play is a standout.

The cast have excellent chemistry together and are skilled comics. They each sell and enunciate their lines expertly, and the production does not lack for laughs. Whilst they are not the most experienced, it does not show. With that said, it does lack almost entirely in the sexuality one might expect from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a casualty of Bell Shakespeare’s family-friendly slant.

Ultimately, Peter Evans has directed a very impressive production of one of Shakespeare’s Dream. Whilst there were flaws in its execution, the production’s genuine attempt to bring something new to a play with such a fixed identity is admirable. In many ways, it succeeds in this attempt. It is running until March 30, and we absolutely recommend that anyone with a passing interest in The Bard check it out. Our showing culminated in speeches, drinks, hors d’oeuvres and a friendly mingling with the cast, making it a night to remember for years to come.