The narrative of the Australian bush offers us a utopian mirage, a depiction of land that is enchanted by the colonial imagination and embedded in its Indigenous heritage. It is widely exemplified in the desire to move from the big cities towards living in regional and remote communities in the hope of solving our ever more detrimental environmental and economic crises. However, the viability of such a solution is weak, only bolstered by a collective misunderstanding of our relationship with the bush. As such, we must actively dismantle this long-standing narrative of the ‘bushtopia’, which only serves to create further degradation and debt.

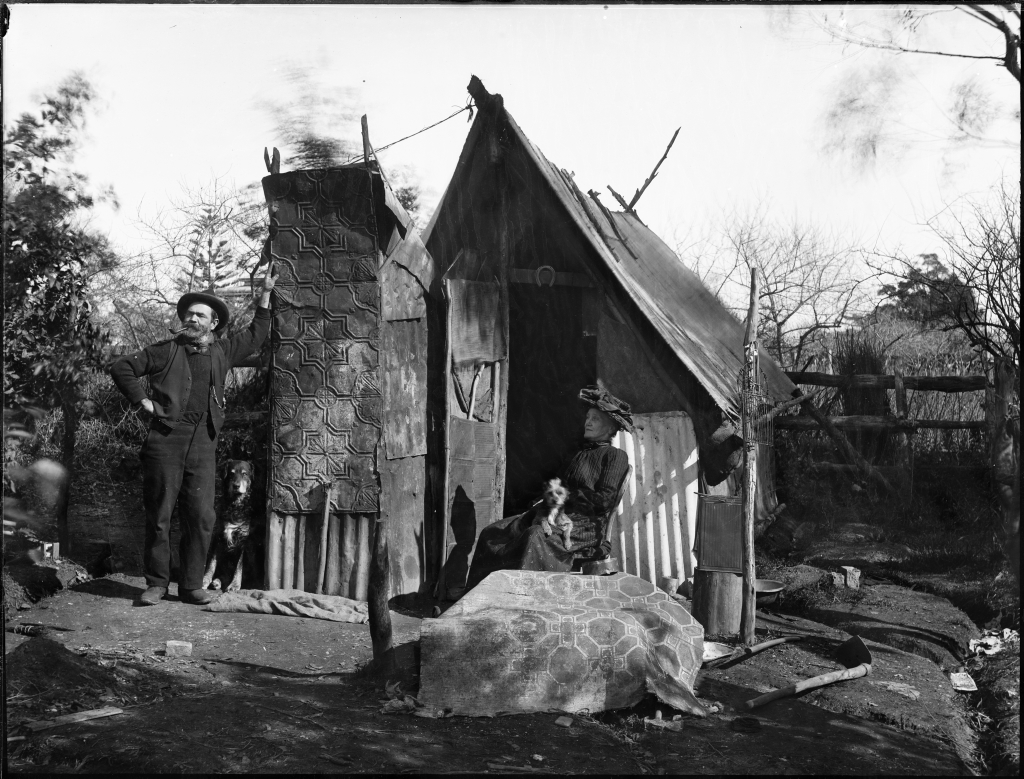

In the colonial understanding, the bush is a place defined by its existence as the ‘other’, as external from the fabrication of modern humanity. The bush holds a cultural legacy through occupying a rich literary canon, including that of Henry Lawson and Patrick White, who populated the common imagery with desolate landscapes, homesteads, and dusty roads. As a result, it is a place where we can be truly isolated and independent. More recently, the dissemination of Indigenous agricultural knowledge through figures such as Bruce Pascoe who in ‘Dark Emu’ has begun to reform this narrative into one where the bush is a place of custodianship and connection.

Connecting this to our current state, out-of-city migration has increased throughout the past decade with 2021 witnessing close to 12,000 Australians moving to regional cities and remote communities. My family and many others have partially or fully committed to leaving major cities for regional hubs and communities in the search for independence, self-sufficiency, and the key to a more sustainable future.

We can also understand these motivations in the context of the student experience; with the decades of rising house prices in cities culminating to a point where an independent future is impossible without an inheritance, it is tempting to view a future in rural areas. This is compounded by the dread of losing the climate war, embodied by what feels like a chronic lateness of the government in providing solutions.

Thus, tied in to ‘bushtopia’ is an anarchistic desire to look away from collective government solutions, toward individual action — and so it becomes alluring to embrace the cultural narrative of the Australian bush. Houses are cheap, community is strong but not imposing, and environmental motivations are at the heart of decision-making.

However, the reality of living in the bush heralds the need to deconstruct our conceptions of the country. While nourishing our nature-starved souls, low-density living won’t necessarily solve our contemporary economic and ecological crises.

The problem resides in the very tension between our conception of ‘living in the bush’ and its less-than-ideal reality. Propelled by the partially innate, partially culturally conditioned desire to integrate ourselves within natural sites, we automatically assume our presence indicates a mutually beneficial relationship. Similar attitudes follow the consumption of locally produced items — their status doesn’t preclude them from being ecologically harmful. This facilitates an individualised form of greenwashing, embedding our perceptions of the city as a man-made polluted mass, and the bush as a natural, never-changing utopia.

As such, the bush presents a difficult economic reality. Under capitalism, it may seem far-fetched to move into areas engaging in a “circular economy” where goods and services are produced locally and waste is minimised.. True self-sufficiency is close to impossible if we wish to maintain our modern lifestyles with the mass production of everyday-use items and components that cannot be created locally. For example, the very fire trucks vital to ailing climate disaster just cannot be made without manufacturing. In turn, the state continues to prove itself as an essential actor needed for sustaining communities and providing crucial transport infrastructure.

The base argument resides within economic efficiency and the creation of economies of scale. These ideas similarly apply to ‘big backyard’ suburbia, since the average distance between residential areas will increase as our regions grow. So will the amount of resources needed for infrastructure creation, maintenance, and the time taken to transport goods and people. Roads are exceedingly expensive with construction costing on average approximately $6.2 million per lane per kilometre (2017 CPI inflation-adjusted), in addition to supporting infrastructure, as well as maintenance and repair which sometimes costs more. Larger projects like WestConnex are projected to cost between $0.5 to $1 billion per kilometre depending on estimates. These transportation needs will increase fuel usage and entrench car dependence, while the state will be left to pay ballooning infrastructure expenditure.

Culturally, some communal spaces and essential services will be lost if more people commit to bush living. Unfortunately, it cannot be economically justified to build large social spaces like stadiums, libraries, and sometimes, schools, in areas with low population density. For example, essential services like public transport are not provided in the area where my family resides. The local school sustains one teacher and limited resources, therefore many residents prefer to send their children to schools over one one-hour commute away, increasing car usage and wasting productive time in commute.

Bush living also encourages us to build larger houses and utilise more land because it is cheaper to do so, thereby losing the advantages of space and energy-efficient architecture within city terraces and apartments. Furthermore, stand-alone houses with high surface area exposure to the highly variant Australian climate preclude either high levels of insulation or copious use of air conditioning and heating. Predominantly Australians use the latter, currently boasting a horrible average score of 1.8 stars out of 10 in the national house energy rating scheme (for reference the minimum for new builds should be 6).

Ecologically, land use for a small house in NSW is high owing to the requirement for land clearing of 25 metres around a property deemed necessary to reduce bushfire risk. This means that one small house can require hundreds of trees to be cleared, thus aggravating the loss of large habitats and biodiversity. Paradoxically, the presence of wood from cleared trees as excess fuel load may increase fire severity and risk.

These factors all lead to the idea that the ‘bushtopia’ is fundamentally wrong. When I first experienced the Australian bush, I thought I was cheated. The landscape I saw was a dense network of sprawling eucalyptus, rocks with wombat shit perfectly laid on top, and lomandra grass with a vendetta against my legs. I expected wonderfully European plains interlaced with swaying long grass and the occasional eucalypt. This vision is not the Australian bush but a colonial import, a terraformed habit destruction that occupies not only our minds and literary canon but, as a result, large swathes of inhabited regional areas.

This argument, while simple, feels intuitively wrong:why can’t it be environmentally friendly to get closer to nature? Are we not just modern-day hippies? While we can reduce harm, put up more artificial habitats, produce locally and sustainably, use insulation, generate renewable electricity, and regenerate native species, this is just not the most efficient use of resources on a broader scale. Not to be mistaken, it is important that our rural areas become more sustainable, as they are important to our economy, facilitating intra-city transport and underpinning our food systems. The point is, bush living is not the solution for the everyman.

Nevertheless, the mythological appreciation of the bush is solidified, all that is yet to do is re-write the underlying narrative. Culturally, aesthetically, and spiritually, the bush lives up to these substantial beliefs, and you only must spend one moment there to understand. We can’t fix the problems with bush living unless we dispel capitalist values and reach self-sufficiency akin to the Indigenous stewards before us. As currently this feels expressly impossible, instead, we must vanquish our enchantment with ‘bushtopia’ and refocus our limited attention on living co-dependently and fixing our cities.