“Is there an Australian who doesn’t know the particular tough pleasure of lying on a threadbare towel on concrete, nestling your pliant young body into that hard, baking warmth?”

So asks Charlotte Wood in her introduction to Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip (1977), a book that has become something of a modern classic. Though her analysis of Garner’s work is evocative and exciting, Wood seizes the Melburnian landscape and tries, ambitiously, to shape a synthesised Australian literary identity in a way that seems, to me, anxious and almost feverish. She uses unceasing repetition: Monkey Grip “sold and sold”, capturing Australia’s “blue, blue air” and the 70s hippy lifestyle of going “gig to gig and house to house”, almost as if the more she says it, the truer it becomes.

Her phrases are stitched with polysyndeton to create the illusion of coherence: Monkey Grip makes her think of “blinding sunlight and suburban swimming pools”, or “hot concrete and chlorine”. These fragments of sentences are briefly aesthetic, sitting nicely on the tongue and teeth due to their consonance, but the images they evoke are generalised, transient, vague; too reductive to successfully argue for ‘Australianness’.

Wood’s urge to claim a recognisable literary identity is understandable in the recent cultural-economic landscape. The majority of English-language books are published by five companies — Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, Macmillan, and HarperCollins. Each decision made by these publishing giants is instantly reflected in the chain bookstores that dominate book retail, creating a literary hegemony. Most of these companies are based in the US or in England, which, as Helen Garner herself has said in a Paris Review interview, makes Australian writers feel anxious “that they [have] to account for themselves and their place in the world.”

One curious, undeniable fact about the Australian book industry is that while chain bookstores have declined over recent years, independent bookstores seem to be thriving. While local bookstores have been around for decades, 86 Dymocks bookstores in 2005 became 46 in 2023 while American megachain Borders opened 26 stores in Australia only to eventually go bankrupt.

If bookstores are at the forefront of shaping a literary culture, why is it that Australia’s strong community of indie bookstores yields such a fragmented literary identity?

I visited a cluster of independent bookstores in Newtown to gain the bookseller’s view of Australian literature. The general consensus was that Australian literature was disjointed, but there were varying perspectives on the merit of having an embodied, cohesive literature.

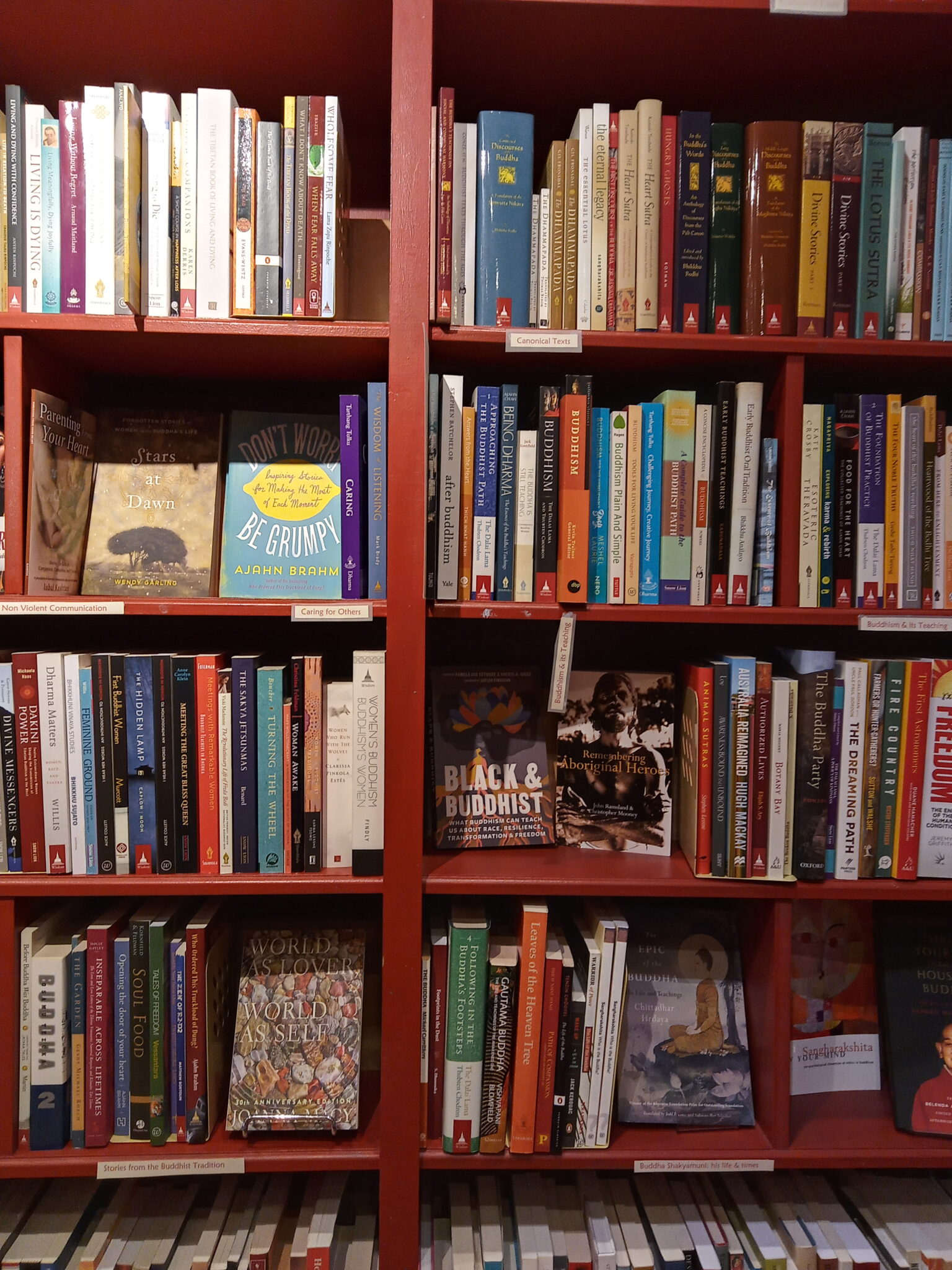

Bodhi Books & Gifts, an unassuming but put-together bookstore specialising in Buddhist spirituality, represents one niche of Australia’s literary community. The bookseller detailed how Buddhism has influenced the Australian arts, especially celebrated Australian poets like Robert Gray and Judith Beveridge. When asked whether Australia’s literary identity was distinct to that of other Anglophone spheres, they replied, “yes and yes, especially in terms of landscape.”

Geographically, Australia’s landscape is unique — a vast island in the south, filled with harsh deserts and coastline settlements. Myself and most people I spoke to had the experience of being taught that Australian literature was about “the Bush” in early schooling. This was an alienating experience as a second-generation migrant who lived in suburbia and had no interaction at all with the outback.

A lot of early English-language Australian literature is by white settlers who “either romanticise the bush, or look at its deadly nature, both of which are kind of false representations,” said the Bodhi bookseller.

At Better Read Than Dead (BRTD), a bookseller agreed that “geography is important [in creating identity], but not specifically the nation.” Because the nation is made up of so many moving parts — First Nations peoples, English settlers, and diasporic migrants — Australians have strong ethnic and cultural roots across borders.

One way that Australia has been trying to shape its literary culture, as I discussed with the BRTD bookseller, is via literary prizes, such as the Stella Prize, the new Novel Prize, and the Miles Franklin Award. Prizes can be core to Australian literature, especially in terms of funding, but they do run the risk of creating a culture where literature is tailored to the prize, “creating a cultural monolith,” or making “a flat aesthetic.”

Elizabeth’s Bookshop has a nonfiction Australiana section which stands out amidst novels from every other continent. Elizabeth’s is a community-driven secondhand bookstore who has noticed that the only people who ask for Australian recommendations are tourists trying to get a grasp of their destination. “It’s terribly hard to recommend an Australian classic because Australian fiction is so varied,” one Elizabeth’s bookseller said.

There didn’t seem to be an anxiety in Elizabeth’s about the Australian literary identity; Australia, just like a community bookshop, is a holding-place for the lives, stories, and voices of its multivarious inhabitants.

As such, the success of independent Australian bookshops, many of which are specialised or secondhand, speaks to the strong diversity of Australia’s literary community. Perhaps it’s not cohesive, and it can’t be summed up by an object or phrase — certainly not by “swimming pools” — it does, however, thrive with interesting niches.

Australian literary culture comprises the kind of stubborn, fierce loyalty that keeps tiny stores in business whilst airy, sprawling chains collapse around them. It also presents a multiplicity of voices, some indistinguishable from other Anglophone literatures, others rooted to one specific Australian landscape.

Ultimately, each voice and community is so different and so irreconcilable that it raises the question of whether we can claim a cohesive ‘Australian’ literary culture at all.