Note: According to the SWANA alliance, SWANA, instead of Middle Eastern or Middle Eastern and North Africa (MENA), is a more appropriate label because it serves a decolonial purpose. It forgoes the generalisations of “Near Eastern, Arab World or Islamic World” which uphold the Eurocentric and Orientalist values used “to conflate, contain and dehumanise” people of the region. I will be using this term throughout this article.

My thoughts about Dune Part: II were perfectly articulated when Timothee Chalamet’s character, Paul Atreides, struggles with the spice in Fremen food, and Chani (Zendaya) mockingly says, “too spicy for the foreigner?”

There is no doubt that Dune (1965) by Frank Herbert is a seminal text. Denis Villeneuve’s Dune (2021) and Dune: Part II (2024) can also be objectively described as exercises in aesthetic and technical achievement. However, the world of Dune being stripped of its South West Asian/ North African (SWANA) influence, and then witnessing this conversation deliberately circumvented, has marred my cinema-going experience. This piece is not intended to convince anyone to dislike Dune but it must be recognised that there are deep-seated issues with the filmmaker’s choices.

I remember listening to a podcast by The Middle Geeks Episode 31: ‘Dune’ Review in 2021 that covered this ground. Unfortunately, the discussion remains the same. In fact I noted down two quotes that still resonate today. First, “it is strange to have a film that is explicitly about imperialism in the Middle East, but not have anybody that reflects that” and my personal favourite, “you can take out locations, our music, the way we dress, the way we adapted to the desert lifestyle, language, religion but you can’t show our fucking faces.”

In a story known for its dismantling of the hero’s journey and concept of the religious (white) saviour, Dune also perpetuates it, with the Fremen people being descendants of Muslims.

Rather than it being a tale of oppressed — Fremen — and oppressor — all the Houses, not just Harkonnen — Paul is motivated by revenge for his father’s death, and the Fremen only become relevant to his quest under the guise that he is liberating them.

From the mention of jinn as a joke, to the manner of prayer being similar to sujood (سُجود) or sajdah (سجدة) in Islam, guerrilla warfare similar to that of anti-colonial tactics, Timothee Chalamet being nicknamed ‘Usul’ (أصول), and the reference to Fremen as “rats” (yes, it’s a crucial plot point but cannot be separated from real-world statements), I genuinely felt uncomfortable in the cinema. The Fremen identity is not adequately developed, and is a selective amalgamation of SWANA cultures, as if they are a monolith.

Instead of being situated in Paul’s outsider perspective, the film could have been framed through the perspective of the Fremen, namely Chani. This was a missed opportunity because Villeneuve shifts her characterisation from unquestioning concubine to someone who simultaneously doubts the prophecy calling him the awaited messiah. Chani’s trajectory felt one-note at times, however, Zendaya played her with conviction with the final scene ringing true to Chani’s earlier statement, “we believe in Fremen.”

Stilgar’s (Javier Bardem) ‘Middle Eastern’ accent compared to the American voices around him was ridiculously justified with “he is from the South”. At one point, the South is also deemed as “uninhabitable”, a statement which felt especially jarring considering how this rings true for the south and all of Gaza, Palestine experiencing dehumanisation and genocide.

There is only one Arab in the cast, Souheila Yacoub, who plays Shishakli, Chani’s friend. Her purpose in the film was to mock Paul, suddenly believe in his mission, and then heroically die (off-screen) at the hands of the psychotic Feyd-Rautha (Austin Butler). In somewhat more comforting news, the film employed Arabic-speaking extras and crew because it was shot in Jordan and Abu Dhabi.

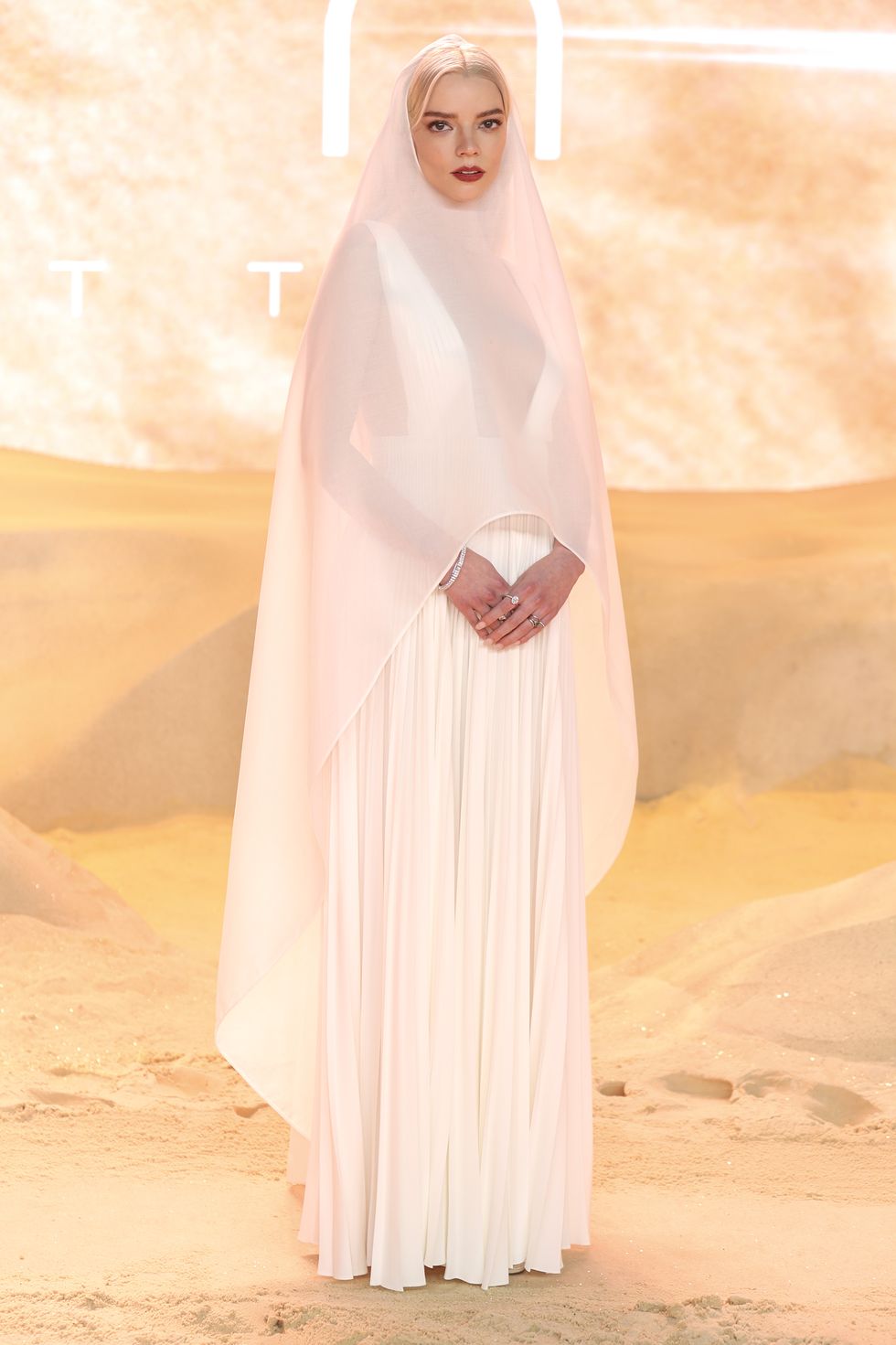

As for the marketing campaign and press tour, Anya Taylor-Joy wore Dior by Marc Bohan spring 1961 couture to the world premiere, which prompted criticism. It is not that no one can wear a veil, headscarf, or any head covering, rather it is that when a SWANA person does so — especially Muslim women — they are not treated with the same reverence. This look can be classified as cultural appropriation as it becomes romanticised in a Westernised context and separated from its original context.

This was also seen with the clothing of the Bene Gesserit with Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) wearing costuming inspired by a multitude of cultures, including Bedouin and Amazigh. While I would arguably say Ferguson was the best performance, seeing her in this appearance without these cultures being explicitly mentioned as the inspiration felt like a betrayal.

Many have argued in defence of these costume choices, and by extension the film, as critiquing the white saviour trope and cultural appropriation. However, you can only critique so much while ignoring the possibility of casting SWANA actors in principal roles and involving creatives that could have easily helped contribute to a nuanced exploration of this dangerous trope.

Taylor-Joy has been cast as Alia Atreides, one of the most important characters in the entire franchise. Besides the fact that Alia is not going to be pronounced as عليا, but as Ah-li-y-a, why was this not an opportunity for an unknown or established SWANA actress? Oscar Isaac can be cast as Duke Atreides because he is the go-to actor for ethnically ambiguous roles, but an actor like Tony Shalhoub, Tahar Rahim or Khaled El Nabbawy cannot be considered. What about actresses like Hiam Abbass, Yasmine Al Massri, Yara Shahidi, Alia Shawkat? Even Salma Hayek would have been somewhat sufficient.

As for the Fremen language, “Chakobsa”, it was created from scratch by David J. Peterson. This New Yorker article quoted Peterson’s Reddit comment where he confidently claimed that “the time depth of the Dune books makes the amount of recognisable Arabic that survived completely (and I mean COMPLETELY) impossible.”

Because of that unnecessary logic, mispronunciation of Arabic, Persian, and Turkish words was rampant from “Mu’addib” (teacher), “Mahdi” (expected messiah in Islam), “Lisan Al-Gaib” (tongue of the unseen) to “Padishah” (King/Emperor).

I, like Paterson, could not recognise some of the Arabic words anymore.

In an interview with Stephen Colbert, Villeneuve talked about a dialect coach whose role was to ensure accuracy in pronunciation. After shooting a complex scene, Villeneuve was happy with the take and ready to move on, but the dialect coach signalled an issue with pronunciation. Villeneuve responded, “Come on brother, it’s a fake language.”

I am focusing my criticism on Villeneuve because I know that he can do right by a SWANA story, as exemplified by one of my favourite films of his, Incendies (2010). Set in an unspecified war-torn Middle Eastern country, it is based on a play by Lebanese-Canadian Wajdi Mouawad, with Villeneuve involving Arab actors and crew.

He said at the time, “I didn’t know a lot about Arabic people. So in order for me to adapt the screenplay, I had to be a listener… Half the movie I re-wrote while talking to actors there. And the challenge for me was to be faithful to Arabic culture, but I think we succeeded.”

During Dune: Part I’s press tour, I could only find one interview where a SWANA journalist spoke to Villeneuve in 2021 and asked about SWANA influences within Fremen. Villeneuve responded that he believed he was faithful to the source material, and that it is “a culture that I deeply love by the way, because it’s a very complex world.” In 2024, Villeneuve only acknowledged the influence of the Arabian desert on his cinematography in an interview with The National.

I had to browse for reviews by SWANA critics and journalists such as Roxana Hadadi and Siddhant Adlakha. Ayan Artan summarised it aptly: “It’s not a critique of colonialism – it’s an example of it…. Villeneuve can never be convincing in his criticism of Paul Atreides because he, in many ways, is Paul Atreides.”

I even found my thoughts conveyed in a CNN article by Noah Bertlasky:

“This isn’t an accident or a blip. The refusal to see colonised people as central to their own stories is part of colonialism in itself. Paul feels bad for being the destined one; Herbert and Villeneuve, to varying degrees, seem to regret making Paul the destined one. But Paul doesn’t ultimately listen to Chani, and neither does Villeneuve. Dune: Part Two purports to show us a freedom struggle on an exotic and distant planet. But it tells the same old story of power as ever.”

I contacted Hanna Flint, critic and author of Strong Female Character: What Movies Teach Us, who despite publishing a review on the film, experienced the effects of “a press run that has restricted access to talent for SWANA critics eager to seek answers about the Islamic, North African and Arab influences appropriated for the film.”

“Where mostly white interviewers and influencers get time with the director, writer and cast, those like myself have had their requests denied. I was told there wasn’t enough time to speak to Denis for an interview I had been commissioned by the BBC to undertake. If I hadn’t been such an outspoken critic of the cultural appropriation and Erasure of MENA actors, maybe that request would have been fulfilled,” Flint said.

She also spoke to rife anti-Arab and Islamophobic sentiment, and that it is not unusual for MENA voices to be silenced or sidelined.

“This discrimination is more than apparent in a Hollywood system that takes from MENA culture but rarely allows talent or artists to have control or input on those narratives. That Dune is a sci-fi franchise makes it more difficult to convince people of the theft and erasure but there are voices like myself who will continue to interrogate cinematic representations and malignment of the Arab world and its diaspora.”

A Dune adaptation in 2024 cannot be oblivious to the representation discourse surrounding it. Even Herbert did not play coy about his authorial intentions when writing Dune in the 1960s, as revealed in the biography Dreamer of Dune (2003). If I wanted to watch a dystopian science-fiction without any overt SWANA influence, there is Star Wars, and when I want a more comprehensive portrayal of the oppressed rising up against the oppressor, I will resort to The Battle of Algiers (1966).

I will tune into the next instalment, Dune: Messiah, hoping that Villeneuve and his team are listening because they have the resources to address these valid concerns. I, and many SWANA viewers, do not want to keep discussing what is omitted from the storytelling, and there is time for improvements.

In the meantime, I will listen to The Middle Geeks Episode 63: ‘Dune: Part Two’ Review.

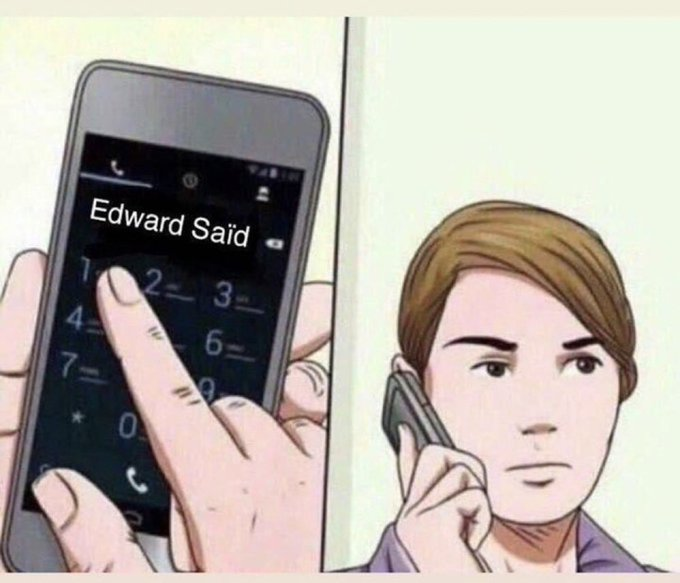

The meme.