How might the distribution of food chains intersect with the division of wealth in Sydney? Have a play on the map below.

Are we missing something? Let us know and we’ll add it to the map!

(The Source Bulk Foods, Vintage Cellars and Cha Time have since been included, thanks to your suggestions).

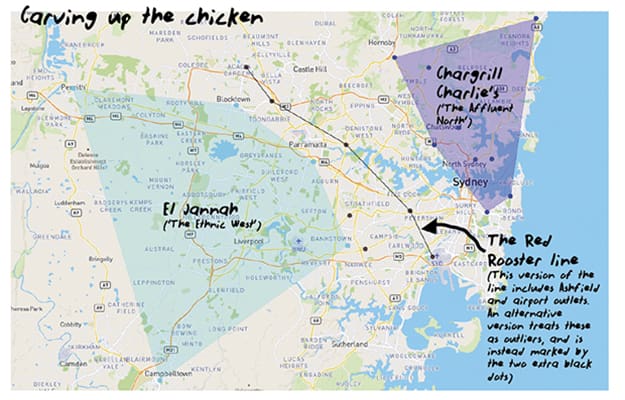

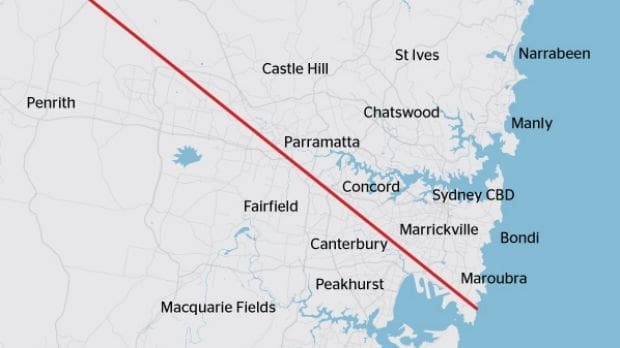

A term that first surfaced on Reddit and Twitter, the ‘Red Rooster line’ has since entered common vernacular as a dividing line which separates Sydney’s west from its more affluent areas. The formula is simple: sketch the points of all the Red Roosters in Sydney and you get a surprisingly neat indication of the border of Western Sydney.

According to Bernard Salt — who is most famous amongst our generation for penning a scalding take on the smashed avocado habits of millennials in The Australian — the suburbs that lie beyond the Red Rooster line constitute “a different world orbiting the city like an asteroid belt at a distance of 7km to 50km from the CBD.” With a touch of anthropological flair, Salt asserts that: “Different people with different values inhabit different space.”

Salt proudly dubs the Red Rooster line’s inverse the ‘Goat Cheese Curtain’; an area he describes by waxing lyrical about hipsters roaming in search of avocado and, well, goat’s cheese. The curtain is drawn around 38 cafes that have been rated four out of five by at least 500 reviewers on Zomato, and its parameters stretch across from Haberfield to Bondi, and from Newtown up to the Rocks.

But there’s more to the line than the simple opportunity to scoff at the café-dwelling habits of Sydney’s hipster élite.

The concept of a border that splits Sydney down class lines doesn’t just exist online or in the musings of News Corp writers: the ‘latte line’, as it is also known, is a concept used in city planning. “If you are north of that line you are largely a ‘have’,” according to Geoff Roberts, the economic commissioner of the Greater Sydney Commission. “If you are south of that line, you are largely a ‘have-not’… It’s a concept that says employment, education levels, social disadvantage, all the things that make a city less productive and less liveable than what we would all desire, you can pretty much draw a line from the airport through Parramatta, just to the west of Parramatta up to the north-west sector.”

The ramifications are clear in education too: HSC outcomes by school can be charted clearly on either side of the line.

The distribution of fast food outlets in cities is often cited as a typical indicator of socioeconomic class. A 2002 study of Melbourne by Reidpath and colleagues collected data on the number of fast food chains per postcode, testing McDonald’s, Pizza Hut, KFC, Red Rooster and Hungry Jack’s. When the results came in and the highest income postcodes were compared with the lowest income, the latter were shown to have two and a half times more fast food outlets per person.

So beyond drawing the lines around a ‘hipster/suburbia’ divide, what else can drawing maps around the distribution of chains in Sydney tell us about different parts of the city?

We took the liberty of drawing our own lines around Sydney and naming them in similarly alliterative ways. While most orient themselves neatly in clear blocks around the latte line, some afford the map-enthusiast greater specificity than others.

Our Google Maps adventures also revealed some more trivial patterns: the locations of Gelato Messinas and Bailey Nelson stores, for example, almost perfectly overlap — each existing in concentration around the gentrified and hipster inner city, while also ticking boxes in key shopping districts like Parramatta and Miranda, to ensure their scope just extends to more suburban parts of Sydney.

But from the ‘Great Dessert Divide’ — an easy way to map the city’s gentrification — to the ‘Harris Farm Hedge’ — which carves the clearest picture of Sydney’s richest regions — it becomes clear that residents of Sydney today are on footing that’s far from equal.

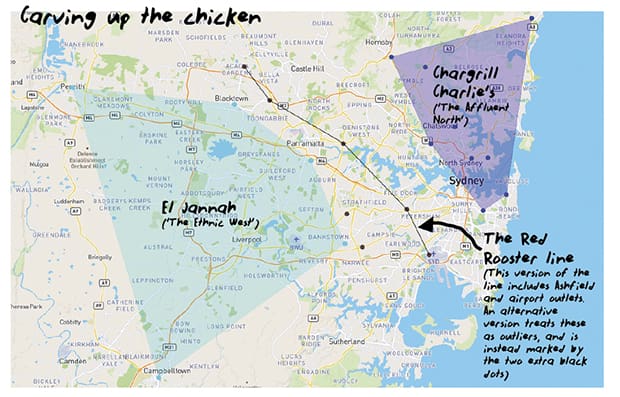

Carving the chicken

If we take a look at the map below, we see that while the Red Rooster line divides Sydney clearly in two, other chicken outlets carve sections of Sydney off into more defined quarters.

The line drawn by El Jannah, which serves delicious Lebanese cuisine alongside its chicken, establishes an alternate gateway into Sydney’s west.

This line is perhaps more accurate than the Red Rooster line, which in itself is controversial for encompassing the airport and the Inner West suburb of Summer Hill. El Jannah is at its furthest east in Bankstown, so offers a clearer geographical delineation. Moreover, the joint’s ethnic twist is indicative of the demographic contained within its tasty borders.

As the Red Rooster line sweeps to the west, so the North is held neatly by a ring of Chargrill Charlie’s. Venturing further north than Salt’s Goat Cheese Curtain to encompass suburbs like Mosman and Mona Vale, this map encapsulates Northern Beaches affluence. On the weekend that this paper was produced, a Chargrill Charlie’s was opened in Annandale. This venture means the Chargrill Charlie’s line extends into the rapidly gentrifying Inner West for the first time, making this map one to watch.

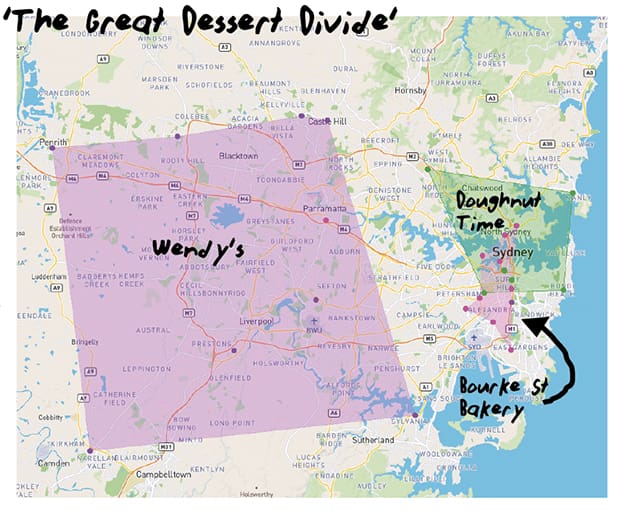

The Great Dessert Divide

With the entrance of relatively new pastry purveyor Doughnut Time, we’ve seen the pastel green shopfronts become slowly more common, but only in a select area: three are in the city, and the remaining four are in the Northern Suburbs, Northern Beaches, Inner West and Eastern Suburbs respectively, outlining a quadrilateral of relative financial comfort.

Bourke Street Bakery has an even more limited scope; its locations are mostly concentrated to a narrow corridor stretching from North Sydney to Eastgardens, and its one outlying Parramatta bakery makes sense when you think about Parramatta’s extensive shopping district and developments. Bourke Street’s various outposts delineate what is essentially the city centre and its surrounding trendy suburbs.

Contrast this with the city-outskirts favourite, Wendy’s, whose closest store, bar the one kiosk in Moore Park Supa Centa, is 15 kilometres away in Sylvania; Wendy’s once had more stores open around Sydney, but many have since shut since they were not financially viable.

Doughnut Time is principally concentrated in the city and Inner West, speaking to its status as an overpriced, gimmicky, gentrifying trend; it has also targeted more affluent areas like the Northern Beaches and the Eastern Suburbs where such a store might find success.

Wendy’s, on the other hand, reliably traces the western side of Sydney, a territory untainted by gentrification — for now.

The Harris Farm Hedge

To consider the ‘Harris Farm Hedge’ — the portion of Sydney where you can find upscale supermarket Harris Farm Markets with its aesthetic store layouts, broad range of protein snacks, ‘imperfect picks’ section, and the option to fill your own jar of fresh milk — is to acquire a picture of class in Sydney that’s more insightful than dwelling on the simpler ‘hipster’ demographic indicated by the Goat Cheese Curtain.

Stretching as far north as the Chargrill Charlie’s map, but reaching substantially further west, the Harris Farm Hedge fits quite snugly into the part of Sydney that has been sectioned off as home to those who are the ‘haves’ of society, according to the latte line’s followers.

Out of all the maps, the Harris Farm Hedge is the only border which encompasses all 10 of Sydney’s richest suburbs (Point Piper, Vaucluse, Bellevue Hill, Mosman, Hunters Hill, Northbridge, Woollhara, Double Bay, Paddington and Balmain). Given that six out of these ten are Eastern Suburbs locations, it’s only fitting that the East is the region with the highest concentration of Harris Farms — you can find a whopping three separate stores very close to one another in Bondi.

This clear division of food suppliers along class lines evokes the concept of ‘food justice’: the idea the dominant food system — from production to distribution and consumption — often upholds inequalities that exist in wider society. In line with this, research has repeatedly focused on how healthy food options tend to be less available in neighborhoods home to residents with lower incomes. Recognising this, proponents of food justice demand that: “disadvantaged communities benefit as much as or more than privileged people from efforts to strengthen local, healthy food systems.”

The proliferation of Harris Farms in this shape makes sense; it is logical that the most expensive and wealthy areas of Sydney would be the go-to for expanding an upmarket grocery store. However, when considering notions like food justice, the fact that certain goods and services are restricted to bubbles where wealthier classes reside smacks of their potential to perpetuate structural inequality. Harris Farm’s distribution is an example of the market in action, but is the market just?

Steakhouse Square

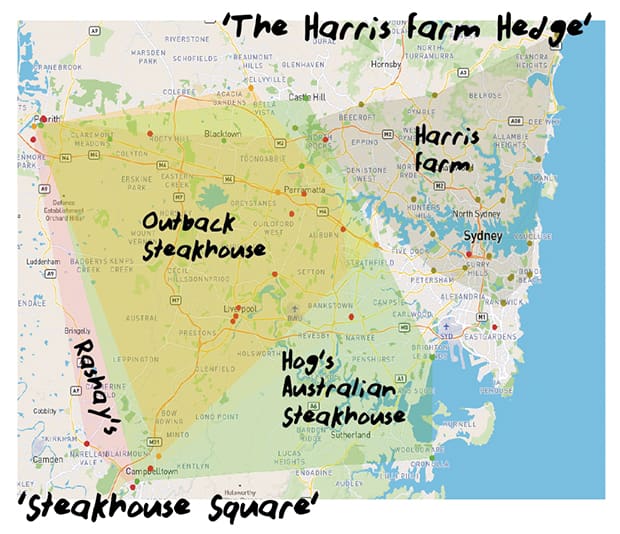

Operating in near perfect inversion to the ‘Harris Farm Hedge’ lies what we have identified as the ‘Steakhouse Square’. Though we’re taking slight liberty with the square form, many of Sydney’s most prolific steakhouse chains can be found here.

Rashay’s, whose restaurant name originates from a combination of its founders’ names, Rami and Shannon, started in Liverpool, and since then has spread as far up as Penrith and as far east as Eastgardens. However, 16 of the 18 Rashay’s restaurants sit within the map’s red polygon (Liverpool alone is home to three Rashay’s stores), excluding the city and Eastgardens, which we’ve treated as outliers.

Outback Steakhouse and Hog’s Breath, or Hog’s Australian Steakhouse, occupy pretty much the same territory; if we had to guess, we’d say their distribution corresponds mostly to areas of Sydney with larger middle class families, away from the ‘café culture’ and hipsterism of the city and its surrounds; these restaurants, while not necessarily more affordable than your average chain restaurant, are often spacious and able to accommodate larger groups of people.

Beyond that, it’s hard to draw more meaningful conclusions, since it’s such a large expanse — our question is, what is it that stops them from expanding north-eastward?