This article does not uncover some hitherto unknown story about our colonial past. It merely reaffirms what local First Nations communities have known for centuries: the Great Hall is built over not only stolen land, but a sacred burial ground.

Gai-mariagal man and academic Dennis Foley, who worked at the Koori (now Gadigal) Centre in the 1990s, presented an oral history as told by Foley’s grandmother, Clarice Lougher, her half-sister Eunice Watson, and their cousin Willie De Serve. “My mother’s family knew that area… and my father is a Glebe boy, so I have knowledge on both sides of the family about the different Aboriginal stories of the place,” Foley said in a February interview with Honi.

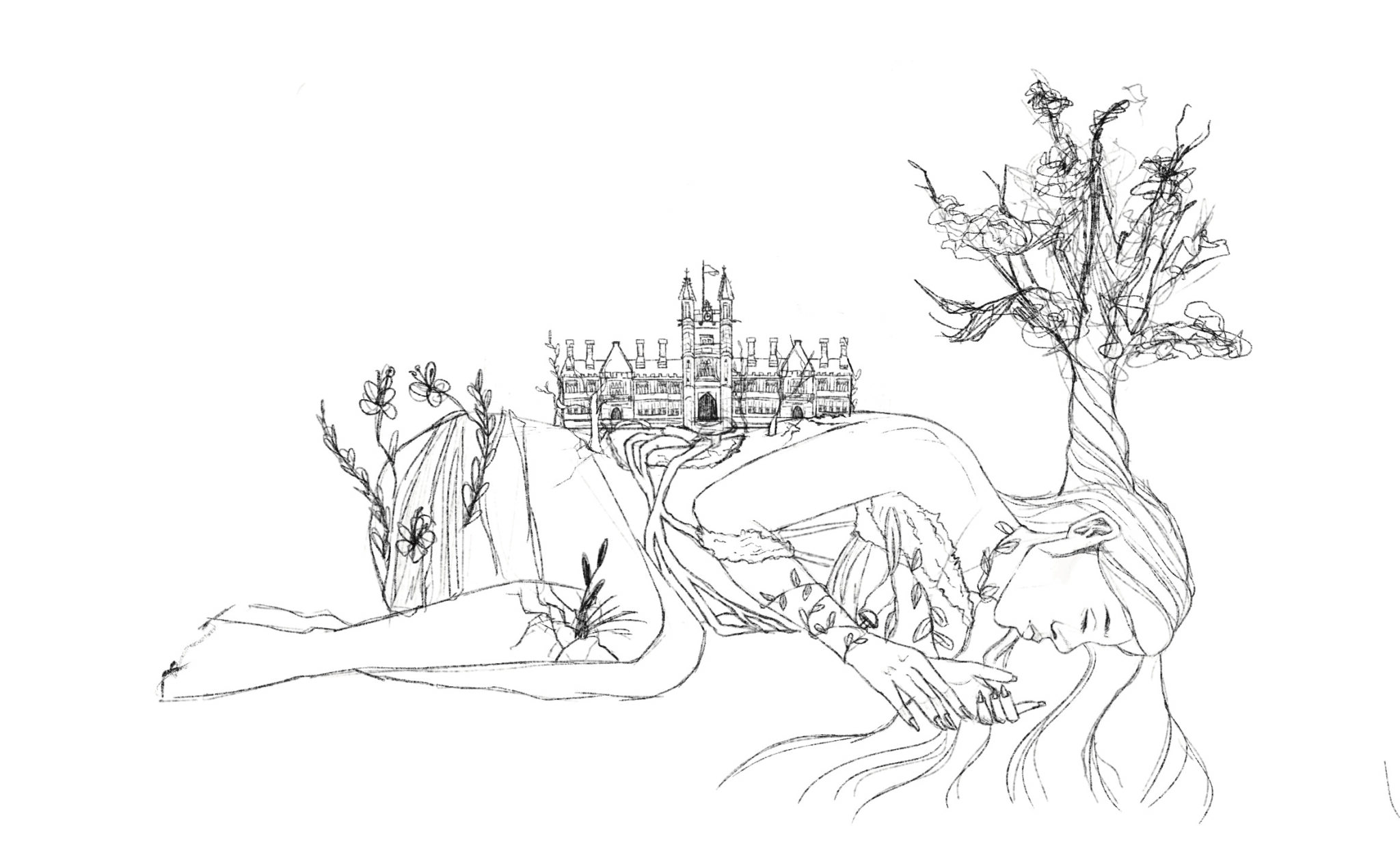

Their account attests to the deep cultural and spiritual importance of the land, but its greatest revelation is that the Great Hall stands on a “sorry site” – a once ancient angophora forest, and a burial ground within: “after cremation, wrapped bones were placed in… the hollow trees. … perhaps that is why it is so cold there?”

Before my conversation with Foley, I presumed that the existence of the burial ground was not widely known in scholarly circles here at the University of Sydney.

Certainly, I had not encountered the story of the Wiradjuri labourers involved in the Great Hall’s construction – Foley’s patrilineal ancestors. Several died during construction. The remaining workers “walked off the job” and “refused to go back there.”

“They said it was cursed.”

This is how the story resurfaced, decades after the angophora were deforested to make way for a colonial military encampment and later, farmland, in the 1820s and 1830s. According to Foley, the colonists left a paper trail behind them, detailing their destruction: when the trees were felled, the human remains within were revealed. This knowledge has not been published or made public or accessible by the University, but, as Foley affirmed, the story “should be well-recorded,” languishing in the archives as latent and untapped evidence.

While the University has continually voiced its commitment to makarrata and truth-telling, it is surprising that there has been no public statement, and so no acknowledgement, of this history. When the University commissions works by Indigenous artists, it comes across as virtue-signalling, and when it delivers acknowledgements of country this is merely paying lip service, if these acts are not matched with genuine attempts to recognise, recover, and honour the Aboriginal history of the land on which the University stands.

However, this is not to say that there have been no attempts within the University to reckon with its colonial past. Foley conceded that “the university made a concerted effort to uncover the sites” some time ago, when Billy Griffiths, now a historian at Deakin University, wrote a paper titled ‘The Aboriginal History of the University of Sydney’. This truth-telling project, the remnants of which I found floating around, unmoored, on the internet, does not appear to have been concluded, let alone embraced. According to Foley, the University caved to pressure from lobbyists affiliated with external institutions, including the Australian Museum and the land council, who “sought to discredit the oral history.”

“That’s the world of anthropology and archaeology. It’s driven by white knowledge.”

Foley said. “They say ‘well, unless it’s written down, we don’t believe it!’ Well – hang on – we didn’t write things down! And that’s the trouble! We have a vast, rich oral tradition. We’re an oral culture.”

This is a common criticism of Australian history in our ‘history wars’. However, as my interview with Foley demonstrates, in this case it is wholly inapplicable.Because there is written, documentary evidence. And yet, in Foley’s words, it is “evidence that they’ve denied.”

It must be said that, long before the University’s frustrated efforts, local First Nations communities campaigned for the recognition of these histories. Foley said that “Darug people, Wiradjuri people, and some Wangal elders too. They knew about it all.”

Foley emphasised the importance of continuing the campaign, to foster cultural sensitivity and respect for First Nations staff and students.

In Aboriginal cultures, the disturbance of burial sites amounts to desecration, and this is now recognised by Australian statute law.

“It’s a totally destroyed site,” Foley said of the burial ground, “if the University excavated, dug it up again, they wouldn’t find anything… so really what we’ve got is just the odd spirit.”

“We’re a pretty superstitious mob at the best of times,” Foley remarked. Of once being allocated a classroom to teach in what was once the “old morgue”, he said he “chucked a u-ey, said ‘no way’ … you just don’t want to put yourself in that position, whether you believe it or not.”

Truth-telling aside, Foley emphasised that there is further potential for healing. He suggests

that there should be a designated ‘healing site’ where there was once a creek: “something should be done there, to show its [the land’s] importance… You know I used to do lectures out there in the open because of that feeling of goodness.”

This land was once a wellspring of spirituality, a place of lively cultural and commercial exchange, initiation and knowledge. Though, as Foley says, the University has “got this incredible checkered history”, it remains a place of knowledge-sharing “on very, very special grounds”.

It is past time that these two histories are reconciled. But this can only happen if the University of Sydney ceases to bury its past.

This is an ongoing investigation. Foley’s oral history cannot stand alone, without corroboration from colonial, archival sources (as this article has demonstrated) to be seen as legitimate. In the coming weeks, Honi will uncover the evidence, doing research that the University endorsed but failed to realise. If you have any information on this subject or wish to contribute, please contact editors@honisoit.com