A predictable fog rolled over warring planes of discourse after Trump recognised Juan Guaidó, a Venezuelan opposition leader presiding over their Asamblea Nacional, as their Presidente. Like other narcissistic leftist ‘netbros’, we quickly found ourselves encircled by this tempest of states, standpoints, and structures, becoming as much the gust as the trees swayed by it.

Amidst gathering storms we dug our trench. We were opposed to #AmericanImperialism, considered opposition supporters the minority, and believed our opponents perpetrated not only intellectual mistakes but moral ones too. Although not bearing the uniform of any overarching ideology, our foes, in turn, wielded the weapons of centrist liberalism. They claimed Maduro is a #cronyistauthoritarian, believed he ought to resign, and hinted that #AmericanImperialism might be the best of bad options.

And yet, despite the appearance of intractability, our views were not so different.

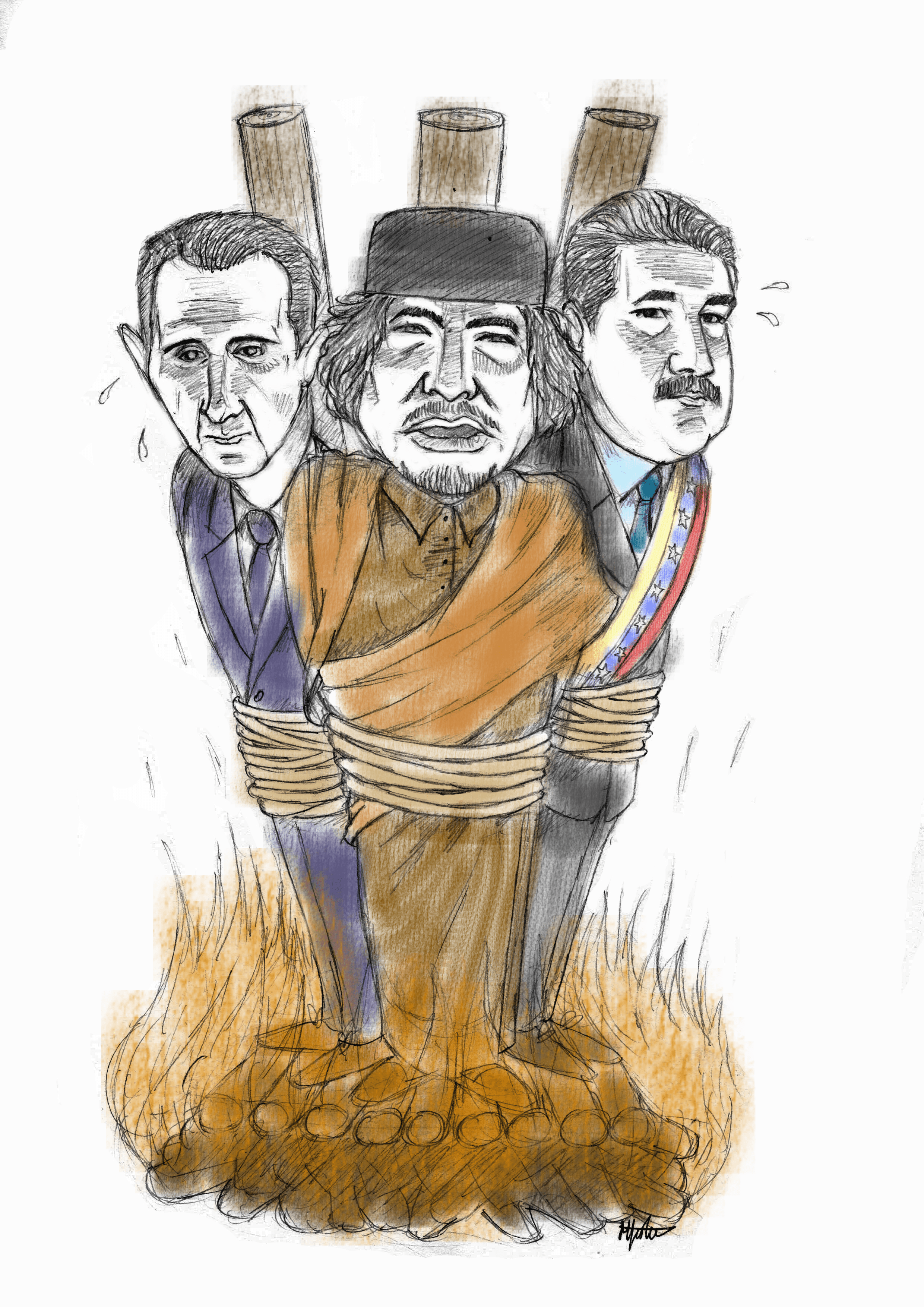

We agree more democracy is always better, despise wanton violence, and support initiatives undertaken in the name of ending oppression. We regret instances where Maduro, or any other ‘least evil’ leader, falls short of ideal standards, and we criticise incumbents where they do. As such, we are only prepared to support select states on a case-by-case basis. But in the foggy war of late capitalist geopolitics, the facts we proceed from, the way we frame our opinions, and the political acts we prioritise or omit affect the success of each belligerent. In the battlefield of ideas, it pays to fire from the right trench.

Uncle Rupert Wants You!

These foes were mere raindrops in the stormcloud of liberal moralism and conservative red-baiting that thundered above the front, the complexity and variety of the mass recalling the hot air blown outward by the Syrian Civil War since 2011. While instructive to other discussion, our analysis therefore primarily reacts to these storm fronts, drawing from and contributing to the discourse surrounding those states.

In both cases, no discursive participant, bar maybe the clandestine lizards embedded in the ruling class, has come to support dubious actors like Guaido or the Free Syrian Army out of moral insensitivity. In fact, many well-intentioned people have responded to particular presentations of facts with appropriate outrage. And yet, by being lead to positions that undermine the least evil option, they ultimately bring more harm to those for whom their hearts bleed.

The corporate media accounts for a great deal of this irony. As historically profitable and well-endowed institutions, corporate and independent government media have a strong material and cultural foothold in liberal democracies. Because of this, they remain the most common way citizens of liberal democracy access information. While competition ensures some ideological differentiation among them, foreign policy positions appear to converge in a way otherwise unseen in the industry, their analysis bound by similar incentives, agendas, and information channels. As these media sources command large cultural capital and attention, especially among the generations where power rests, their editorial decisions and content determines which topics are discussed in mainstream discourse, while also mediating the information available for citizen decision-making. But because citizens’ notionally shape the direction of liberal democracies, the media doesn’t just host discourse but effectuate outcomes too. When engaged with uncritically, the information they convey can lead astray instead of ahead. Media can do this by “manufacturing consent” for political outcomes citizens would not otherwise support.

This concept, first coined by Noam Chomsky, captures how the interests of media corporations align with the imperial ambitions of states to shape the content presented to audiences. Rather than limiting rights to franchise or speech, powerful actors influence the way citizens view their reality, increasing the chance citizens serve the status quo when exercising their democratic rights. Efforts are made to limit the role foreign interventions play in decision-making, often by painting targets of them in ways that balance the moral cost of the intervention. Thus, unfavoured “dictatorial” regimes are subject to exaggerated mischaracterisation, marked by connotative descriptors and the neglect of successful programs, while pro-regime voices are framed as fringe or otherwise excluded. Inconvenient facts and events don’t cross paths with even the most astute news follower.

Dr Alan MacLeod applies Chomskian methodology to media coverage of Venezuela in his book, Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting. He found that America’s State Department directly paid journalists (or “disinformation agents”) to report propaganda as news in both Latin America and the US. In Venezuela itself there is just one full-time correspondent from the mainstream English-language press, and local media are frequently propaganda outlets for opposition groups, themselves funded by American organisations such as USAID, or the National Endowment for Democracy. Journalists in these organisations see themselves as leading the resistance against the government, and therefore have no qualms about publishing fake news to serve that goal, for instance when they erroneously claimed that “condoms now cost US$750 in Venezuela.”

However, one need not believe there is a conspiracy afoot to see how this process could play out. In a capitalist machine each cog seeks to maximise profit. Thus, it is rational for corporate media firms to support initiatives likely to do that — like America trying to bring new states into their trade hegemony — even if they don’t explicitly collude with initiators. And this is to say little of the further role that nationalism and conformity play in determining how each cog behaves, whether that be the intern converting Reuters wires into articles or the executive deciding the careful framing of each fact.

But while material factors explain how the media presents the news to people, ideological factors explain why people choose to believe it. Recent condemnation of Venezuela, especially in liberal circles, owes a lot to the preponderance of identity politics and its corollary “standpoint theory” in contemporary progressive discourse. So successfully have they advanced through the planes of discourse that these days their central insight—that an opinion derived from “lived experience” cannot be challenged—is a starting, and, frequently, final point of analysis.

From Standpoint to Standstill

Standpoint theory contends that those who are most excluded from power are best placed to understand oppression, having lived experienced of marginalisation which is invisible to others. By amplifying the voices of the most downtrodden, beginning with African American women in the 1980s, standpoints’ insights command reverence in progressive and even mainstream circles. This should be expected: once we concede that lived experience is an immutable source of knowledge it seems insensitive to challenge conclusions drawn from such experiences.

With this norm entrenched, it is unsurprising that people react with outrage when one particular person in Venezuela, or a family member, details their plight. After all, who are we detached theory bros to question an anti-Maduro opinion forged in the fires of experience?

To meet the question head-on, we are theory bros who have forged opinions by taking stock of many lived experiences. And herein lies two big problems with uncritical deference to standpoints: firstly, that standpoints about experience are conflated with questions of fact, and secondly that some standpoints are simply more common and well-justified than others.

In this particular case, the pro-opposition stance is not even close to the majority—one poll suggested 80 per cent of the population had never even heard of Guaido—and the Chavista stance is more popular than the alternatives, particularly among oppressed groups. For every unprofitable small business owner there are twenty children who would have starved had it not been for free meals in school; for every exiled gusano plutocrat there are a hundred campesinos able to own the land they farm for the first time; for every 30 per cent who voted for opposition parties in the internationally monitored but imperfect 2018 Presidential elections, there were 68 per cent who voted for Maduro.

None of this suggests that one standpoint is more important than another. It also doesn’t suggest that we should abandon its insights altogether. In fact, the opposite is true: simply possessing or referring to a particular standpoint cannot be grounds for resolving a debate in favour of that particular standpoint, not least when there are conflicting standpoints that deserve our deference just as much.

A norm of uncritical deference to standpoints creates a related problem: empowered actors can use convenient lived experiences to dismiss or obfuscate inconvenient ones. This is especially problematic when our deference cannot distinguish between standpoints undergirded by well-reasoned structural explanations and standpoints motivated by self-interest. This costly theoretical insensitivity ignores an important fact: that though each person might have their own unique experience of reality, what they are experiencing is the same structurally oppressive reality.

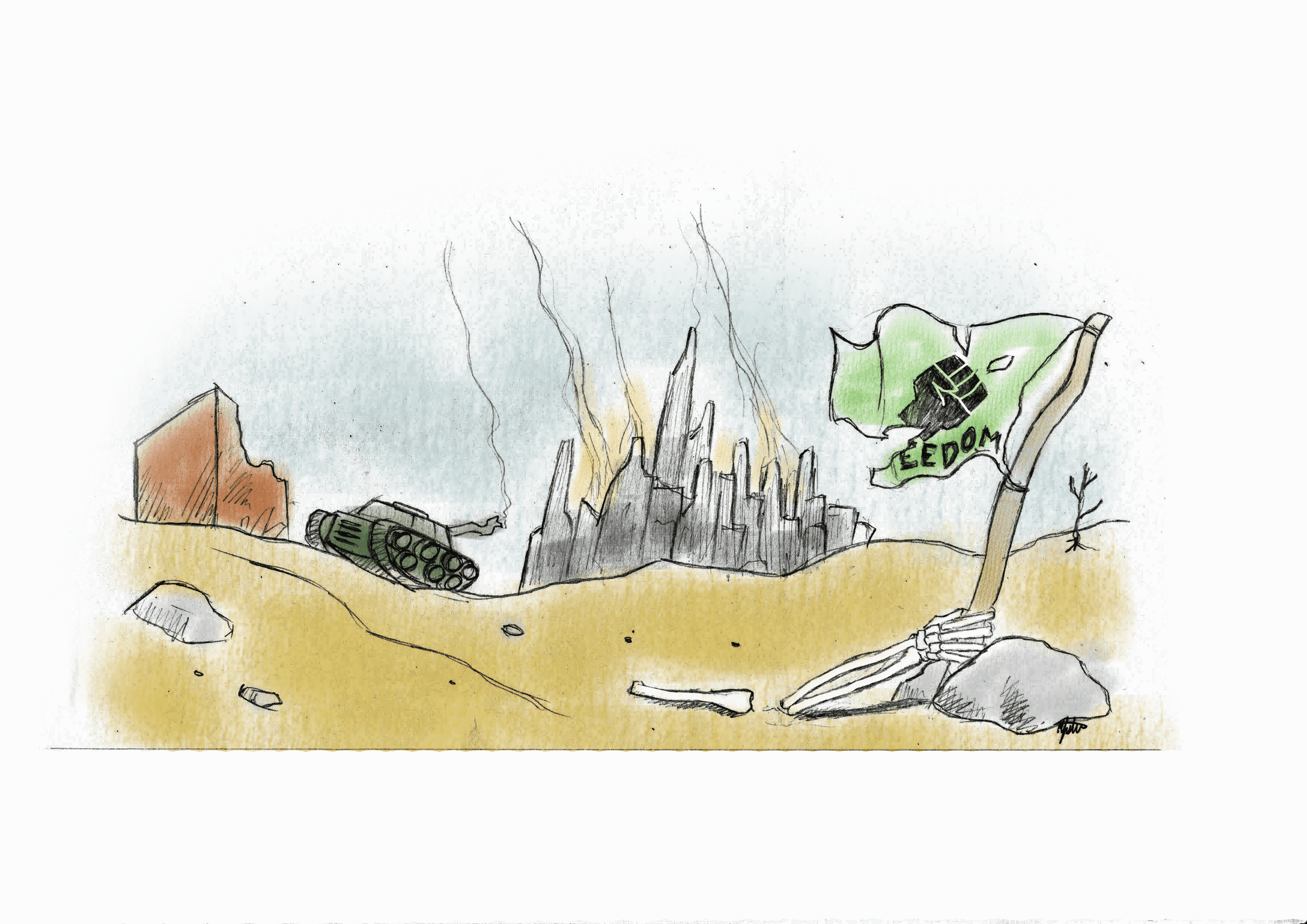

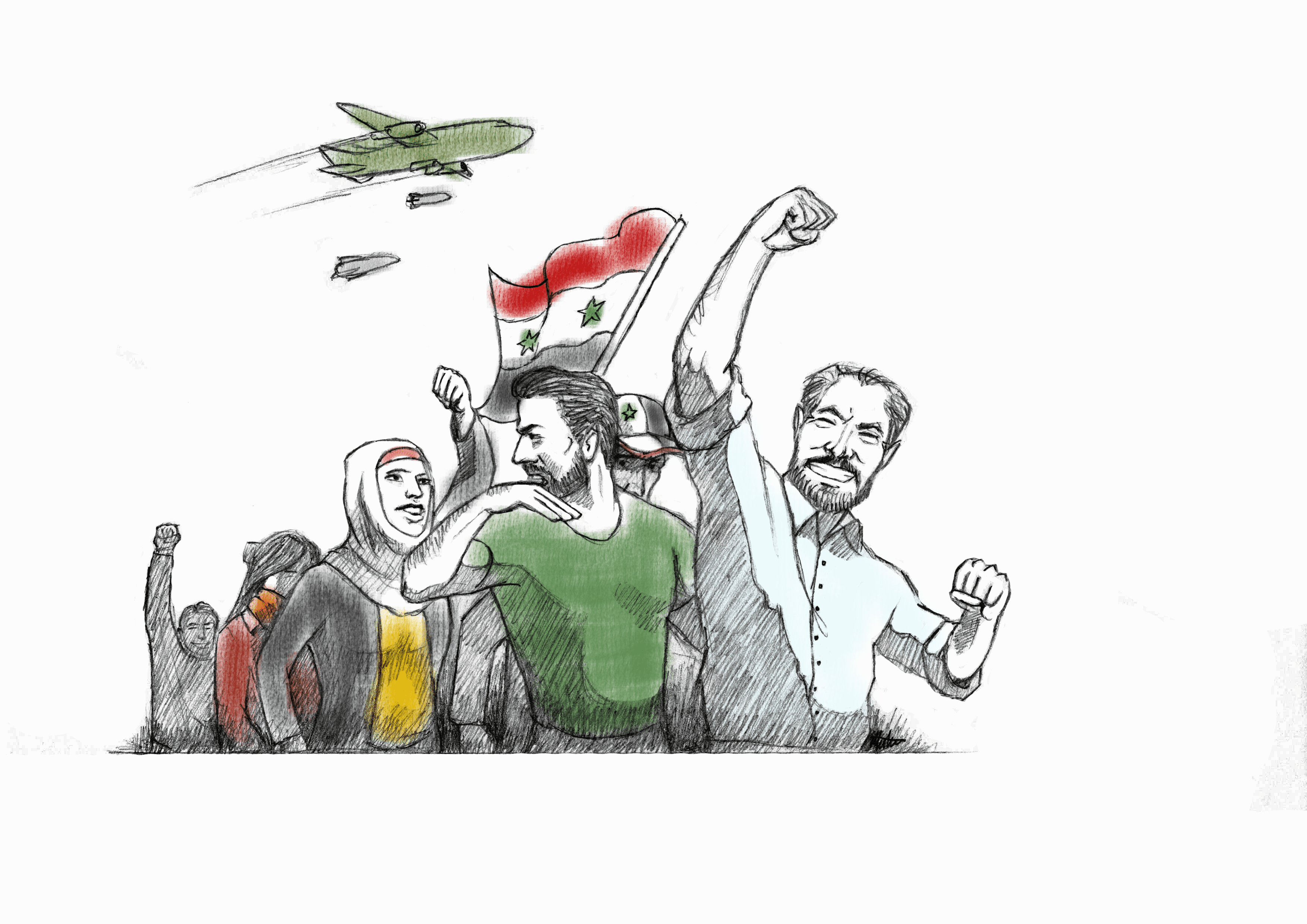

When combined with the media’s reach, the deification of lived experience can lead well-meaning people to bad-ending positions. Thus, we see in Venezuela, as in Syria, that the minority anti-government protesters disproportionately drawn from empowered groups are erroneously seen as a manifestation of the people’s will. Their tales of hardship, at worst the result of mechanisms of redistribution and most likely the consequence of economic warfare waged by the West, motivate the reluctant war cry of the guilty hawk. Consent is manufactured.

The ballot or the bread

But a hawk that put its hunger for justice ahead of its hunger for contrition would spot, from afar, the cues that separate predator from prey. In particular, they would observe that America has used its time as a global superpower to maintain and impose a global economic system that forces countries, firms, and people to accumulate or else face death. They would see that people long-victimised by America and its global economic system invest significant support in leaders who claim to defy this world order, especially when they demonstrate that defiance by giving to the poor that which would otherwise have been accumulated by the rich. They would, finally, recognise that these same people rationally consent to comparatively absolute leadership as an imperfect improvement on the alternatives: barbarism and/or invasion.

These structural dynamics, long-understood by the Global South, explain why incumbents are often preferred to other options when citizens take advantage of whatever democratic rights the state grants. While there are no doubt improprieties in the way these elections are conducted, they are nonetheless often deemed legitimate by international monitors, and independent surveys regularly corroborate election results. And even where incumbents do not enjoy overwhelming support, anti-regime protesters—the kind who support the Free Syrian Army, Guaido’s Voluntad Popular, or any intervention to establish liberal democracy—are an overwhelming minority.

The reason for this is simple. They seem interested in a different social contract to people in the developed West, supporting the authority they judge as the least evil. Without the luxury of being able to wait around for a revolutionary groundswell, or even to fantasise about a benevolent liberal saviour, citizens of these states ordinarily have no choice but to hedge bets on the options at hand. And, in many cases, even those who recognise the value of democracy favour comparatively authoritarian options, especially when the “authoritarian” uniquely guarantees their most pressing needs: protection from violence and the stability necessary for material prosperity.

In regions of the world where want and deprivation are a daily part of life, liberal democracy is a luxury rarely desired. Tunisian intellectual Larbi Sadiki calls this the “democracy of bread,” where citizens of the Global South accept a level of authoritarianism incompatible with liberal democratic norms as a compromise to guard against invasion from without and barbarism from within. Like Syrians who saw what happened to Iraq or Afghanistan, Venezuelans know how external involvement has undermined quality of life, especially in neighbouring countries like Guatemala, Chile and Nicaragua, and have therefore put their democratic ambitions aside in order to better fend off that possibility.

This position not only reacts to external military fears but external economic suspicions too. Believing the Western economic sphere replicates humiliating colonial dynamics, many in the Global South interact in a distinct network of economies neither socialist nor neoliberal. This has, at the very least, altered the way they behave as global economic actors. Many of these states, for instance, refuse trade that requires conversion to US currency, entering alternative trade alliances when Western ones exclude them for pursuing a model that empowers the state more than corporations. A model of this kind at least nominally strives to achieve material improvements for its people and has done so for many in impressive ways Western media neglects to mention. Many citizens, particularly those who know how Western economies treat the powerless in their own backyards, recall the sting of colonialism as they hedge their bets on this model.

The economic exclusion inherent to this deviation makes it harder for these states to reach the threshold of material development, stability, and peace ordinarily needed before extended democratic rights are even thought about. New South Wales, as one example, didn’t establish an elected parliament until 1843. The French bourgeoisie, for another, didn’t foist democracy onto the aristocracy until their proto-capitalist system generated enough surplus for them to become an empowered, critical mass. Sanctions and economic warfare actively hurts ambitions to expand democratic instruments, while also obscuring the way nationalisation can give citizen more ownership over the lives.

You don’t need a strongman to know which way the bomb blows

Contrary to assumptions of a brainwashed and repressed citizenry whose thoughts are bound by propaganda, citizens of Venezuela and Syria are comparatively free from many of the issues that plague the Global South: they have protected the rights of Indigenous peoples and minorities, their governments are secular, and they have committed themselves at least nominally to women’s liberation. While propaganda and fear play into their citizens’ decision-making to some extent, their consciousness is no more false than Westerners.

In fact, the extensive social and economic progress directly encountered by citizens is not something governments or media could lie about, and has mobilised pro-government protests far larger than anti-government ones. That an impressive number of citizens credit incumbents with improvements in their own lives contrasts with Western voters, who don’t so much as vote new parties in as vote the current one out, only feeling their lives have improved when the spin machine positions them to. This explains why a sizable portion of citizens maintain zealous support even when they know of regime atrocities, be that Bashar al-Assad’s violent suppression of protests in 2011, his father’s murderous campaign against the Muslim Brotherhood in Hama in 1982, or Maduro’s imprisonment of high-profile opposition figure Leopoldo Lopez in 2015.

What gives Westerners the right to patronisingly question their judgement while accepting our own system as legitimate? Who are we to demand they facilitate greater evils to preserve ideological purity? On what basis can we possibly conclude that the standpoints of those in the minority trump the standpoints of the majority?

In many cases, these reactions to citizens’ preferences stem from hubristic assumptions, rather than intellectual considerations, where observers assume citizens in favour of incumbents don’t appropriately value democracy. They assume that these people are, at best, experiencing false consciousness, and, at worst, are rationally deficient.

Do not be mistaken: those against the opposition or Western involvement in these countries understand liberal democracy just as well as people in the West. They no doubt have the same emotional responses to repression, injustice, and wanton violence as people in the developed world, and, equally, appreciate what democracy offers as well as any anarcho-syndicalist or Daily Telegraph columnist. To think otherwise is baseless arrogance.

That these people reason to support incumbents, even despite their full and rich connection with the ideals of democracy, goes to show just how evil the alternatives are. Their decision-making no doubt weighs democracy as much as anyone here might, but that particular input is overridden by other inputs us in the West do not have to contend with.

A similar thought process ought to play out amongst defenders of incumbents if it doesn’t already. These defenders should empathise with the plight of those affected by the evil inherent to lesser evilism, supporting those attempting to further reduce that evil. They ought to be troubled by the suffering these regimes subject people to, regretting avoidable instances and hoping for a future where ideal options exist and are realistic. And they ought to bite the bullet, reluctantly, in the interests of the greater good, even where they have the very same phenomenological reaction to victims of imperfect incumbents as those who outwardly signal their disgust.

All strategic on the discursive front

However, bullets of sympathy and conciliation ultimately injure the very people and standpoints they were meant to protect, especially when fired from the wrong trench. In the first instance, ignoring citizens’ preferences is inherently disrespectful, and should be avoided in principle unless we better understand the structures that shape their oppression and bind their decision-making.

Beyond principled costs, these bullets can also cause issues in the realm of consequences. Though one person’s opinion makes no difference on its own, bad thought processes can aggregate, affecting the possibility and nature of collective action. In a context where one bloc enjoys a default hegemony, and that hegemony accounts for the bulk of suffering people face, weakening countervailing forces necessarily creates space for hegemons to grow. When taken together these two facts suggest not only that observers ought to take a side even when no options meets their ideal standards, but also that they should manage their political activity to ensure it doesn’t indirectly lead to outcomes they don’t want.

Thus, condemnations of Western interventions should avoid deference to exaggerated despotism, on pain of encouraging the most evil belligerents to repeat that imperialist mechanism. Critiques of incumbents should clearly commit to their preservation, eliminating the risk that crucial marginal actors, like undecided observers, get dissuaded from investing in projects like ending sanctions. Belief in revolutionary socialism or liberal democracy should motivate organising practices and activism that doesn’t undermine the good features of least evil incumbents.

By accepting the preservation of incumbents as a first premise and avoiding activity that indirectly leads to more evil options, defenders reach the same normative territory as others while enjoying the unique benefit of having started their offensive from the right trench.

That trench is the one we attempted to dig on Twitter: the trench of standpoint-sensitive anti-imperialism. It is one that commits to the battalion even while debate and critique rages in the dugout. It is one that is reluctant to embolden oppositional sentiment, prioritising critiques of the external forces responsible for poor conditions over narratives that already dominate. And it is one that assesses which realistic option is the least evil regardless of the standpoints emphasised, accepting that option as the one worth fighting for until circumstances change.

After all, when the battlefields grow heavy with fog the only way for belligerents to ensure they don’t hit the people they set out to protect is to fire from the right trench.