Content Warning: this article mentions Bulimia.

I went overseas in January and naturally, it’s the first thing I get probed about at cafe tables. I always say that the biggest highlight for me was the cuisine; that “the Pad Thai here doesn’t hold a flame.” But the ironic truth is: I didn’t eat for most of those three weeks.

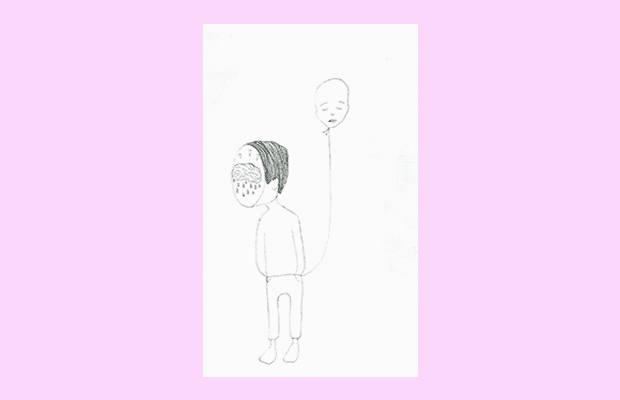

My brain functions in a peculiar way. At every waking moment, I’m frantically calculating how much glucose is in my body; how many fat cells I am burning in a state of ketosis; how much metabolic water my body is producing. When I eat, I can feel these processes spiralling out of control, and it becomes impossible for me to track. Because of this obsession, I go through extended periods of starvation, sometimes without even drinking water, for this allows me to gain a phantasm of absolute control over what my body is doing. This is then followed by vicious relapses of binge eating when my body and mind inevitably yield.

These eating cycles maintain a firm grip over every single facet of my existence. My starvation periods are when I am most productive — to suppress my hunger, I pile on work so I don’t have time to even contemplate food. Many call me a workaholic, but I object to that sentiment since I am not driven by the work itself, but rather the aversion of eating. Because my subconscious is constantly thinking about food, I spend a lot of time cooking and watching cooking television shows. Though it doesn’t sound terrible, during these periods I am miserable and completely devoid of energy.

When I binge, I feel euphoric. Like a desert traveller stumbling upon an oasis, my body finally receives the sustenance it has been yearning for after days of hunger and dehydration. These fervent binges can last up to a week, a period where I am incredibly radiant, happy, and (dare I say) potent. Interestingly, my senses are heightened, so even a sterile piece of lettuce can taste like sugar. But after that comes the slump, where I feel physically nauseous and drown in acute feelings of paranoia. Rinse, lather, repeat.

The curious thing is that my friends and family all know about my eating patterns. In fact, most people point out that I never eat, to which I always answer “I’m just not hungry.” This is enough for people to suppose that everything is fine. While I don’t blame anyone, acquiescence certainly doesn’t help. There are so many times where I wish someone had spoken to me privately and simply said “if there’s anything I can do to help, let me know.”

When thinking about an eating disorder, many conjure up an image of a person emaciated, insecure, and volatile. Yet it certainly doesn’t represent everyone. I feel good about my body. I sit within the average weight range for a person my height and age. I carefully plan out the days and times in which I have my ‘strategic’ binges. But when you look at my patterns of behaviour, it would be absurd not to conclude that something is gravely awry.

The reality is that eating disorders are incredibly complex and manifold. We come in all different shapes and sizes, at all stages of body acceptance, with different habits and pathologies. Not all people with bulimia purge. Collective ignorance, masked in hyper-awareness, has created very narrow definitions that serve to exclude and delegitimise people who are indeed suffering from genuine mental health issues. We start to believe that we’re not “sick enough” or “thin enough” for treatment, even though we torture our bodies physically and mentally every day.

I decided it was time to share my experiences, because in order to demystify the eating disorder and all its nuances, it’s important that we tell our stories. This is but one of many. Though, admittedly, I’m only at the first yellow brick on the road to recovery, I’ve come to accept that just one day of struggling in the darkness of an eating disorder is enough to warrant proper attention and help. I have hope that this will catch on, and that more people will have these conversations.

If you are worried about yourself or someone else, the best thing you can do is talk to someone. The Butterfly Foundation for eating disorders’ National Helpline can be reached at 1800 33 4673, 7 days a week from 8am to midnight. In a crisis, please call 000 or Lifeline on 13 11 14.