Magicians make the impossible possible. They have the ability to mesmerise audiences all around the world. They skirt certain demise. They play with fate in ways no ordinary human would dare. They fall into the abyss, only to perform miracles seconds later; clinching themselves from the jaws of impending death. They rip apart their assistants and seamlessly bring them back to life moments later. In short, they test the boundaries of what we think we know, through the spectacle of grand illusion. Exploiting this spectacle, magicians like Harry Houdini and Howard Thurston were able to draw in an enormous fan base, turning themselves into household names. Unfortunately, their entranced fans seemed to forget the thousands of humble Indians who invented the very tricks for which their Western counterparts were enjoying fame.

The cultural roots of magic in India span across millennia. The origin of the word for a magician in Sanskrit — Indrajala — stems from the Hindu God Indra, who was known for their magical talents. Magic in India, like all magic, was in part of a spectacle for the non-magical society to enjoy.

However, in India’s case, magic also played a critical role in the evolution of religion and, by extension, culture. In many instances, street magicians positioned themselves not as mere entertainers, but a human vessel for the powers of God. This meant that the practice of magic was closely integrated into ancient religious traditions, such as Tantra.

The importance of magic in India is perhaps best illuminated by its ubiquity. In a country otherwise divided on lines of caste, class, religion and region, magic appears to be transcendent. Amongst various Indigenous groups known as Adivasis, elements of magic make their way into spiritually important artistic representations.

Others, for whom the Hinduism involves conquering the transcendent powers to achieve an elevated level of spirituality, consider magic to be a critical element of this process. This is portrayed in the courts of the ancient royalty of India, where the act of magic was deeply ingrained within society. Performers in that era were showered with gifts and praise by commoners and royalty alike.

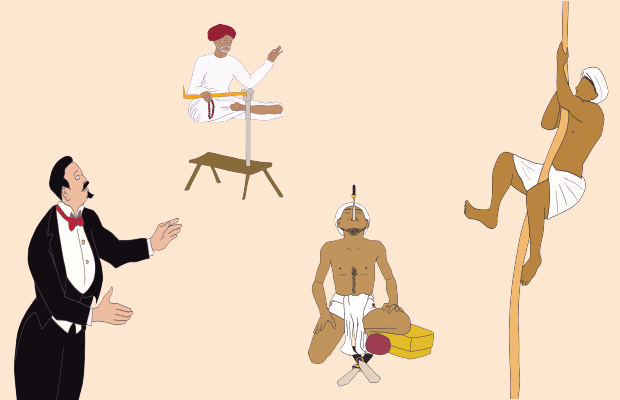

In the royal courts, magicians were sometimes kept as religious advisors to the king as a result of to the talents they possessed. This practice continued into the Mughal era, where Islamic prophets and magicians were also added to the folds of the royal courts. It is during this era that prominent magic tricks (such as the so-called “Indian Rope Trick” and “Indian Basket Trick”) were first pioneered and displayed in the courts of the Kings of the time.

One of the great patrons of Indian magic the Mughal emperor Jahangir, who ruled when the empire was at its peak, made detailed memoirs of the performers he saw. He extolled the abilities of the Carnatic jugglers and sleight of hand artists from Bengal as they performed wondrous feats that stunned the emperor.

He recounts a story where a troupe of seven performers came to him exclaiming that they could perform wonders in exchange for a large monetary reward. True to their word, they performed a vast array of tricks and illusions in front of the Emperor.

Even as British colonialism swept India, the cultural relevance of Indian magic persisted. Families passed down age-old tricks to younger generations as street performers continued to entertain passers-by at busy train stations or local fairs. Indian street performers, however, did not merely settle for their existing illusions. Innovatively, they developed their own acts, tailored for local audiences. For example, performers like Mohammed Chhel became prominent in the Indian magical community not only for their magical talents, but also their engaging personas.

These magicians did not charge exorbitant prices to ordinary people to witness their magic, nor did they have any grand sets or props to work with. Their aim was to entertain those around them and provide an elusive relief from the pressures of day-to-day life for their community.

Unfortunately, like many of the beautiful cultural elements of colonised nations, Indian magic attracted the unwanted attention of prying figures from the West. Various Western magicians, including the likes of Houdini and Bertram, travelled to India in search of illusions not yet seen by the Western world. Fascinated by acts like the “Hindu Rope Trick” and “Aerial Suspension,” Western magicians spent years documenting Indian magic. In many instances, these attempts at documentation were inspired by a sense of insecurity, with the aim of undermining Indian magicians by exposing their methods. In other cases, Westerners would actively steal tricks, claiming them as their own.

Broadly speaking, Western interest in Indian magic caused a paradigm shift in the perception of India from a primitive society of savages to a land of mystery and magic. This appears quite apparent in both descriptions of Indian magic tricks as well as the advertising around Western shows containing plagarised Indian acts. Such depictions exotified Indian culture, and the impact of this persists in contemporary Western attitudes towards the country. However, Western magicians were also incredibly reductive of the diverse and nuanced practices of Indian magic.

Exploiting exoticised perceptions of India in the West, various Western magicians appropriated elements of Indian culture to emphasise the sub-continental mysticism of their acts. For example, in his book Jadoowallahs, Jugglers and Jinns, John Zubrzycki chronicles Harry Houdini’s performances as a “Hindu Fakir.” In these performances, Houdini would apply brown-face and dress in traditional Indian clothes to form an element of intrigue and fascination in his audience. Although Houdini appears to be the most prominent case of appropriation, Western magicians referred to themselves as “Fakirs” well before him.

Insofar as “fakir” refers to a Sufi Muslim ascetic who has taken vows of poverty and worship, names like the “Hindu Fakir” and “The Fakir of Shiva” make no sense. The flippant appropriation of the term also annunciates the broader differences between Indian magicians and their Western counterparts. For Indian magicians, magic held deep spiritual and familial roots. Their commitment to practice transcended pursuits of wealth or any other material possession. This meant that they were willing to perform in public spaces and allow their magic to be accessed by anyone sufficiently curious. By contrast, their Western counterparts were attracted to the business of commercialising their “talents”, investing in grand props and monetising their performances for exclusive crowds. This seems to explain the fact that while Western magicians travelled across the globe in search of acts to steal, Indian magicians were constantly innovating and experimenting.

Beyond the overarching exotification and appropriation of Indian culture, Indian magicians were also directly exploited. In some instances, facing struggles of poverty, they were coerced into selling long-held secrets to Western magicians for a pittance. Those Western magicians would subsequently return home and market these tricks as “never before seen”, receiving widespread acclaim, recognition and wealth. Alternatively, Indian magicians were taken overseas and forced to live in poor circumstances while performing for Western audiences. However, there were also numerous instances of direct theft with no compensation whatsoever. There have been various recorded instances of Westerners, including Houdini, performing Indian street tricks such as the live burial or aerial suspension, and passing them off as their own. It appears then that not only were Indian magicians exploited intellectually and economically, but also almost completely erased from the history of magic around the world.

The legacy of the theft and appropriation of Indian street magic is felt by contemporary street performers in India. While various magicians in the West have continued to enjoy sold-out shows, appearances on late-night talk shows or their own television shows, Indian street magicians have continued to endure class struggles.

In 2014, the largest community of street performers in the world, magicians and puppet masters living in Delhi’s slums – commonly known as Kathputli – were given an order to leave their homes, a place where generations of these families lived practising their art. As gentrification and urbanisation of the city slowly crept into the area, building contractors sought to destroy these slums and ruin the Kathputli community’s livelihood, with no prospect of rehousing.

This was also not the first time that the Delhi local municipality tried to get rid of the group. In the 1970s the entire suburb was bulldozed, only for it to reappear a few months later in a more gentrified form. In more recent times, the protests against the destruction of the colony have become more violent, further escalating tensions between officials and residents. Additionally, new laws abolishing beggary have allowed state authorities to attack street performers attempting to carry on the legacy of their ancestors.

Many prominent cultural ambassadors for the art such as Puran Bhat (a famed puppet master, who has received India’s National Award for the Traditional Arts) and Ishamuddin Khan (once a busker, but now a famed magician performing in Europe and Japan), cite that the destruction of the suburb will scar the tradition and culture that has been practised there for years. Despite many of these performers being under the auspices of politicians representing India and its culture on the global stage in recent years, pleas to save the area have fallen on deaf ears. To this day, the Asian Heritage Foundation is keeping the livelihoods of the performers afloat as finding them ‘gigs’ to further their careers and the art.

Where the state has allowed street magic to exist, it has been reserved for tourist hotspots and showcases for Western travellers, crystallising the artificial notion of a “spiritual journey to India.” This forces magicians to adhere to the aforementioned exoticised Western expectations, and prevents Indians from enjoying the spectacle of magic in ways they were once able to.

Unlike groups who traditionally agitate against cultural theft and appropriation, such as class privileged diaspora communities, in the modern global context, Indian street magicians seem relatively powerless. There seems to be little interest in agitating for their recognition or providing them with a larger platform through which they may gain prominence. Given this, Indian magic may well become yet another aspect of traditional Indian culture lost to imperialism. The West has always profited off the exploitation of the cultural and material wealth of the subcontinent. On this occasion, they simply chose to steal what made us magical.