I love elections. They’re my equivalent of the Super Bowl. Though it’s foolish, I’m still enamoured by the grand idea of citizens, just for one day, holding the fate of characteristically arrogant politicians in their hands. So, last week, I signed up as a polling official to get into the thick of election season.

When it hits 6pm, polling booths across the country get a brief reprieve before the first challenge of the night: unfolding the metre-long Senate papers, akin to laying a tablecloth, and removing the informal votes, those ballots that are incorrectly filled out. And as the votes rolled in, I began seeing informal votes stack up, one after the other, until they formed a tall pile.

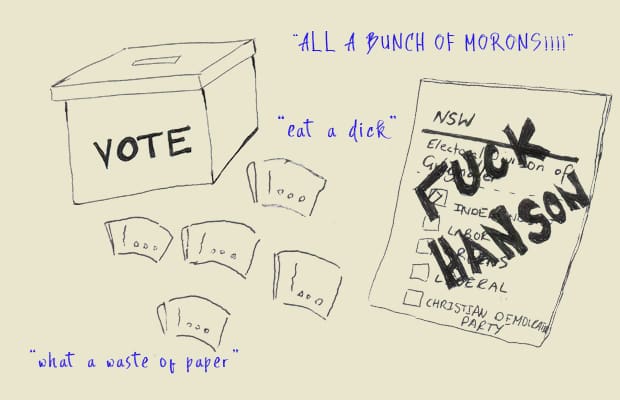

It was interesting to analyse those informal votes. Many possessed artistic talent; I counted ten penises and a detailed portrait of a corgi, and elsewhere I heard of a whale that spanned the entire length of the Senate paper. Give people a rule, and it seems they’ll find a way to disobey with creativity and flair. More common were comments laced with anger, at politics (“ALL A BUNCH OF MORONS!!!!”), at the process (“what a waste of paper”, “eat a dick”) or at specific politicians (my favourite, simply “Fuck Hanson”).

One voter wrote a veritable monologue on their ballot. “Sorry — nobody thinks about us,” they claimed. “They all preach, say, promise to get into power — and then they forget who put them there. We don’t matter.” It was filled with a combination of resentment, resignation and despair that was powerful, yet futile. Who did they think would see it, apart from a polling official so far removed from decision-makers who actually run the country? Even more perplexing were the completely blank ballots, voters who made the effort to turn up and wait in line, and then decided they didn’t want any say at all, formal or informal.

Initially I thought informal voting was simply a callous waste of a precious right. What was the point? And while that might be true, I now think there’s more nuance to it. In some small way, the point was rebellion. What I saw were voters so disenfranchised from the system, so apathetic about its importance, that they didn’t expect anything from it. I don’t think any of them believe their ballot will actually find its way to someone in power or trigger an epiphany. And the positive feelings that arise out of expressing frustration with political leadership is arguably more irrational than earnestly engaging with politics and agitating politicians to change dire situations. While I agree that people have a duty to educate themselves politically, not just for their own sake but to understand how their vote affects others — the thing with democracy is that on polling day, you have to take it as it is.

In a 2016 post-election paper by the AEC, the informality rate was described as “a key measure of democratic health.” That year, the informal voting rate in the House of Representatives was 5.1%, and 3.9% in the Senate. From those numbers, I can’t confidently conclude that politics, on a macro level, is broken. Maybe the reality is not as exciting as people want. Working at an election is repetitive, arduous and devoid of the spectacle I’d expected — but nevertheless insightful. For one, you forget how many people live where you live. From kind elderly couples who held each other’s hands in the voting booth, to 20-strong ethnic families whose kids sprinted around the hall (one asked me for a ballot paper so she could vote for Angelina Ballerina), the interpersonal conversations I had were the best part of election day.

Maybe there’s something to be said about reframing our democracy in terms of those human interactions and how we sustain each other. Whether it’s highlighting human impacts in policy debates, or making the experience of polling not so intimidating, we’re a better, more informed populace when we’re more cognisant of what our vote means, and when we’re less inclined to draw penises on our ballot papers.