I’m really cold.

Not because it’s the middle of winter. No, it’s actually 26 degrees outside – I should be sweating.

Instead, I’m bringing a cardigan and a travel mug of peppermint tea to uni today.

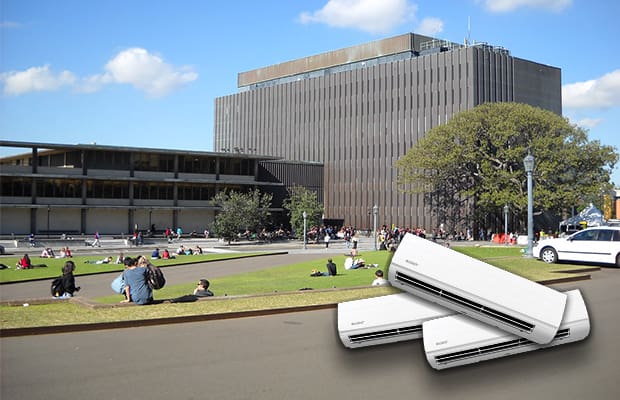

Why? Because I know there’ll be Antarctic temperatures in every one of my lecture theatres and tutorial rooms today. If I dare to wander into Education or ABS, I’ll have to bust out my extra-thick socks and heavy-duty woollen coat to make sure I don’t get hypothermia.

I’d love to say I’m exaggerating. But as I sit in Fisher, those seated around me are visibly shivering.

I do get it. We’re in Australia, it’s hot, we’ve got to make sure we don’t let one millilitre of sweat drip from our bodies. USyd is also a financially well-endowed university. Naturally, we enjoy showboating our shiny air conditioning units around wherever we can.

But mostly, I find this penchant for excessive air conditioning pretty confusing. Every room I enter on campus, regardless of the season, I’ve felt that the level of artificial cooling is genuinely excessive. It always seems fixed at a temperature that would be entirely unwarranted unless it’s: a) a freakish 40 degree day or b) all of us have just run a marathon and staggered into class immediately afterwards.

I just feel like everyone in Fisher would be able to enjoy studying without their snot turning to icicles, if we turned the aircon off for a second. Even used the fan. Or did something wild like, I don’t know, opening a window (it’s pretty damn stuffy in here).

It’s actually unrelenting. Often when I walk into an entirely uninhabited classroom, it’s already freezing. Whilst some of the university’s air conditioning is centrally managed by Campus Infrastructure Services (CIS), cooling systems in older edifices are managed by teachers and students themselves – where, from my experience, little attention is paid to whether the cooling is left on between classes, or even overnight.

USyd does currently hold an “Indoor Air Quality & Thermal Comfort” guideline, developed by the Safety, Health and Wellbeing Unit twenty years ago. On perusal however, this document merely outlines the “optimal indoor thermal comfort conditions” for a classroom, without clarifying how these conditions are to be achieved, let alone monitored. Leading to my current, teeth-chattering writing conditions.

Yet even more concerning than my current set of goosebumps, are the stats on the terrible impact this overzealous chilling has on our climate.

Aircon units are the most electricity-hungry appliance in the average home. They use 10 to 20 times more electricity than a ceiling fan. They consume hefty amounts of non-renewable energy that contributes to the depletion of our ozone layer and ultimately, to global warming.

It’s enough to make your blood run cold when you realise that CIS switching the aircon to “arctic” 24/7 isn’t making us cooler, but hotter.

It’s a damaging cycle, and it’s time to find an exit point.

USyd has been vocal in its commitment to assist the climate, with its self-lauded ‘Pave the Way’ campaign raising over $2 million for environment-related causes in 2018.

However, this only left me wondering why the same commitment is barely demonstrated in its excessive air conditioning.

Student Services told Honi that they “are working on reducing our energy consumption and appreciate support”. Additionally, they reported having a “focus on energy efficiency” in 2019, and are attempting to rollout a motion sensor program for air conditioning units.

But improvements are still lagging behind the rate of climate damage. More monitoring systems are needed to ensure classrooms, especially those locally managed, are not ignorantly contributing to the larger movement of environmental devastation.

Yes, being a tad chilly in my lecture is not a big deal and I can easily “just bring a jumper.” I’m also aware that we’re not the only institution barely lifting any fingers to reduce our carbon emissions.But surely, we can lift one far enough to turn off the AC for a minute?