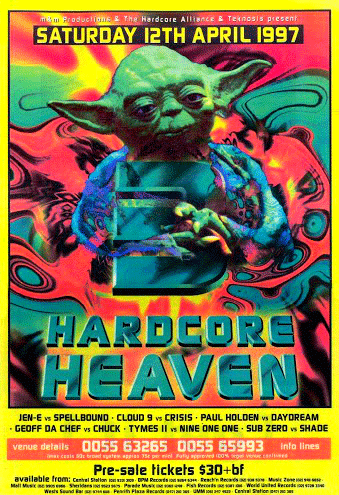

From the mid 90s, New South Wales was home to an abrasive, globally-respected network of hardcore techno producers with a cult following. In Newcastle, Australia, Mark Newlands founded the label Bloody Fist Records with two fortnightly dole payments. Cornered by smoke stacks, barbed wire, steelworks operations and concrete, the label became a production line of its own for a pinball machine of eclectic hardcore beats. Meanwhile, Geoff Wainwright, aka Geoff Da Chef, aka The Hardcore Fiend, pioneered Blown Records, which released similarly in-your-face tracks.

With titles like Shitbeater, Fuck Anna Woods and Cunt Face, these early hardcore tracks pin you down and forcefully inject post-punk angst with a steamrolling dose of tall-poppy syndrome – all while telling you to lighten up. Bloody Fist artists lurch between hip-hop, terrorcore, gabber and scratching with exhilarating speed. The music earned the nicknames “amigacore” and “cheapcore” because producers (proudly) used archaic, Amiga computers. Traces of this DIY, cut and paste mentality can be found in the production of later, Australian breakcore artists, such as Passenger of Shit and Melt Unit. What Australia’s east coast possessed was something distinctively Australian and a group of producers and DJs unafraid to mock the nation’s cultural cringe.

In Sydney today, however, there are almost no spaces in clubs or in the underground rave scene dedicated to hardcore. Certain rave organisers caress the edges of the hardcore spectrum with their sonic brands and support hardcore artists, while promoters like Gabber Central, Noize Disorder and Nightvisions host occasional club nights. A devout group of fans keep the scene alive but there is stagnation in the quantity of events after logistical and financial obstacles arrested the momentum of the 90s and 00s.

While hardstyle artists are always a safe booking for big music festivals like Midnight Mafia and Defqon, it is often risky for promoters to book an international artist whose repertoire focuses on authentic hardcore, speedcore or breakcore.

The promoter behind Hex Yellow, Ivan, highlighted the difficulties in pushing boundaries when I sat down with him: “You need to dangle a carrot in front of heads. The Sydney dance scene is very rigid. You really need to take people by the hands. If you negotiate, you can do it. The results can be good. It’s not enough to tell someone ‘this music will be really good in this setting, trust me.’ You have to give them something they know and love already. You get them comfortable, then you take them into that next space – whether mentally and physically.”

The prohibitively high costs of licenced venues for small communities such as the breakcore scene mean that some promoters and DJs are happy for the parties to remain underground. Fans and promoters have to pool money to soften the financial blow on individuals. Utilising alternative spaces, such as warehouses and bushland, is vital. Recent police clampdowns and exorbitant fines — under the guise of health and safety and fire code violations — threaten Sydney’s artistic growth.

The Sydneysider behind Melt Unit highlighted the benefits and drawbacks of these conditions. “I ran an event called Death Rave for many years, giving a platform for underground producers making experimental electronic music. There was breakcore, chiptune, acid, and all the perversions and combinations within that spectrum. Knowing there was a small audience for it, there was never a possibility of doing it in a venue that actually wanted to make money, so we found our home in other people’s warehouse venues… we didn’t have to worry about making it a viable business… Often whole sets were in-jokes, and we revelled in our own little secret language. There were gabber and speedcore acts that were included in our parties, and there was a big crossover between the two scenes. As our scene was so small we had to crossover to survive, though that was never an intentional goal.”

Another local DJ I reached out to asserted, “the pioneers at the fringes with darker and harder music no longer linger in clubs or licensed venues… The soul of Sydney is still truly alive, although people may need to venture out from the city or inner west to find the leaders of innovation.”

With rave organisers like Hex Yellow rushing to plug the gaping hole in Sydney nightlife for the darker, harder end of the techno spectrum, Ivan touches on a sense of possibility in our conversation — the possibility that we may be entering a post-rave renaissance for gabber, as ownership over techno proliferates. Techno’s rising popularity means that long-time techno heads are “trying to find new outlets that feel more private and personal. Gabber is one of them. Extreme noise and power electronics is another one.”

Part of this movement includes reclaiming gabber from its deformed cousin, hardstyle – a genre that has discarded the relentless drive of hardcore for radio-friendly drops, cheesy samples and nursery-rhyme treble. In 2011, the Italian DJ Gabber Eleganza began to document and archive gabber’s positive, early history on Tumblr. In homage to a man who has pushed forward this revival, Hex Yellow has brought Gabber Eleganza to Sydney for a show in June.

Even in the very names of this rising generation of hardcore artists – Gabber Eleganza, Casual Gabberz, Gabber Modus Operandi – you can see the desire to distance hardcore from hardstyle.

One music video for Nico Moreno’s new track Your Bad Company epitomises this expansion of techno into hardcore. Iconic gabber merchandise dominates. Nike Air Maxs, baggy tracksuits, shaved heads, chain necklaces, scrunchies and Energizer Bunny dancing compete for attention alongside a bouncing beat. A sound and subculture once denigrated is now a symbol of popular rebellion.

While Australian hardcore artists including Geoff Da Chef and Hedonist still produce and tour (mainly in Europe where their cult following resides), they fly under the radar at home. Ivan rallies against the binary images of dance music fans in Australia. He asserts that hardcore not only deserves a place in Sydney’s warehouse, rave scene but that it is particularly suited to these night-time environments.

Calmness amid chaos and yanking people from their comfort zones is the goal: “With my fourth event, the night grew and grew and grew in intensity. It finished with Tim Gollan playing a hard trance, gabber set. I’ve never seen people leave a warehouse party so orderly. Everyone was so tired and exhausted and satisfied.” Later, Ivan told me: “Sure, house and disco is great during the day but putting it in an industrial space, designed for a rave, at midnight does not at all serve its purpose. What is the function of what you’re doing? What is the logic?”

There is hope that Sydney will embrace more experimental and darker music. The success of Soft Centre — a festival in western Sydney combining experimental electronic music, performance art and light installations — is just one example.

As Ivan explained: “There is so much pent-up energy because there are not enough night-time options. When things go right in Sydney, the party can end up being one of the best parties you’ve been to. That’s on an international scale… With the current political and social climate, there is more of a punk attitude in those that didn’t necessarily have it before. More extreme music is permissible and negotiable.”

There is also hope that as the dance music community reclaims hardcore techno, fans, promoters and DJs can rid the genre of its past, toxic masculinity. Women such as Jemma Cole and Alice Joel — part of the quartet behind Soft Centre — have played a vital role in the local hard dance revival and fostering diversity within it, while on a global scale female producers like Vtss and Helena Hauff have become figureheads for a razor sharp, retro sound.

Croy Broodfood, who has released music through Bloody Fist under the monikers Hedonist and Template, notes in an e-mail to me that, while there is not much of a hardcore scene in Australia, he has had a few more gig opportunities lately. “There seems to be a renewed interest in those early or classic hardcore/gabber records or people making music in that vein.”

Many Sydney punters, tiring of techno that no longer feels revolutionary, want to be challenged, mentally and physically. Maybe, just maybe, gabber will return in force.