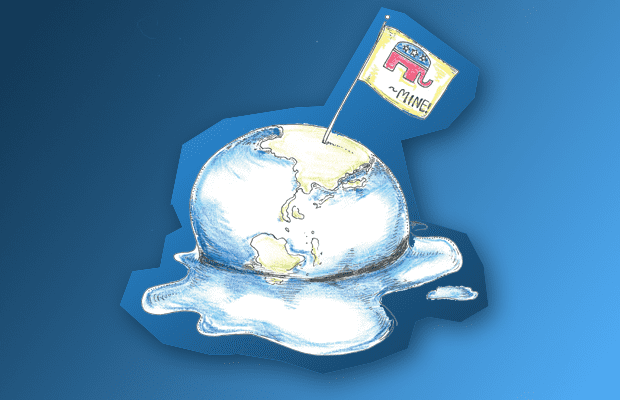

A fixture almost as notable as low taxes, climate change denial or doubt has long formed a constitutive ideological role within the political right in Western liberal democracies. Yet, with the last five years being the hottest on record, there inevitably comes a point at which one starts to sweat — the contradiction between conservative’s claims and a changing climate becomes too great. Accordingly, with the increasing incongruence between their words and the weather, some sections of the far right are embracing the traditionally liberal realm of climate science, and are in turn using it as a framework to push their own reactionary, racist agendas.

In September 2017, American Renaissance, a white nationalist magazine, presented a question to their readership: “What does it mean for whites if climate change is real?” In the ensuing several hundred words, the publication deviated from decades of right wing doctrine in order to propose an ethno-nationalist perspective on global warming. They correctly analysed that changing weather patterns have and would continue to impact poor people of colour in the Global South disproportionately, which would by extension lead to higher rates of migration to the Global North.

Indeed, the magazine wrote that “the population explosion in the global south combined with climate change and liberal attitudes towards migration are the single greatest threat to Western civilisation,” adding that “[this is] more serious than Islamic terrorism or Hispanic illegal migration.” Defending this position, American Renaissance’s editor-in-chief and prominent white nationalist Jared Taylor stated, “I make no apology for… urging white nations to muster the will to guard their borders and maintain white majorities.”

Similarly, on the eve of the 2017 ‘Unite the Right’ rally which saw anti-fascist counter-protester Heather Heyer murdered in Charlottesville, Richard Spencer (perhaps America’s most famous white nationalist) wrote that, “we have the potential to become nature’s steward or it’s destroyer.” He continued, “putting aside contentious matters like global warming and resource depletion, European countries should invest in national parks, wilderness preserves, and wildlife refuges, as well as productive and sustainable farms and ranches. The natural world — and our experience of it — is an end in itself.”

Alt-right Reddit threads concerned with the ethno-nationalist position on climate change generally indicate a simultaneous belief in climate science, and a desire to attempt to mitigate global warming’s effects through violent means, with commenters arguing, “if you believe in global warming the obvious implications are that global migration must be shut down and that all the quickly growing populations must be quarantined or “encouraged” to stop having children.”

Others suggest that only those on the political right truly care about the environment, with comments such as “to be fair, the Third Reich was one of the earliest governments to make conservationism a major focus”, and another user writing, “what really pisses me off is how everyone associated deep ecology with communism and far left ideologies which are deeply rooted in industrialisation. It was Nazi Germany that was environmentally aware not Soviet Russia, with the rabid industrialisation.”

The eco-fascist movement has certainly grown in influence within far right circles as a result of both growing fears of the climate catastrophe and traditional white nationalist arguments about ‘demographic replacement’ or ‘white genocide’. Yet, fascistic ideals have long been premised on a nostalgic natural world, with far right ‘environmentalism’ stretching back to Nazi Germany. In their important book on eco-fascism, Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier note that Nazi ecology was “linked with traditional agrarian romanticism and hostility to urban civilisation”, and that environmental ideas were an “essential element of racial rejuvenation.”

The infamous Nazi slogan blut und boden (“blood and soil”) coined by the Nazi’s principle ‘ecological’ thinker, Richard Walter Darré, and chanted at Charlottesville in 2017, was designed to encapsulate a supposed intrinsic connection between a racially constituted group of people (blood) and the land upon which they live (soil). Nature has also featured prominently in other nationalist movements, perhaps most notably with the white cliffs of Dover in English nationalism. Yet, eco-fascism is not relegated to 20th century history and 21st century Reddit and 8chan threads.

Nine minutes prior to the Christchurch shooter entering the Al Noor Mosque and massacring 50 people, he emailed a 74 page manifesto to more than thirty different recipients including to the New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Arden’s office. His manifesto outlined his motivations for the attack that was about to unfold, where he referenced “white genocide” in keeping with the white nationalist position of ‘the great replacement’ theory. He referred to the Muslim victims of the attack as “a large group of invaders” and referenced British fascist Oswald Mosley as the figure who most influenced him. Yet perhaps most interestingly, or unusually, the shooter described himself as an eco-fascist, writing “there is no nationalism without environmentalism”.

Five months later, in a copycat massacre in El Paso, Texas, which saw 22 people murdered in the city at the US-Mexico border, the gunman’s manifesto was eerily similar to that of the Christchurch killer. He also espoused an eco-fascist ideological view and chillingly titled his four page manifesto An Inconvenient Truth, in an ode to Al Gore’s seminal 2006 climate change documentary. An entire paragraph of the manifesto is dedicated to ecological degradation and a Malthusian philosophy, as he writes that “the decimation of the environment is creating a massive burden for future generations”. “The next logical step is to decrease the number of people in America using our resources. If we can get rid of enough people, then our way of life can become more sustainable.”

There are also indications that far right political parties are beginning to take the climate crisis seriously and are going ‘green’. France’s far right National Rally led by Marine Le Pen has promised to make Europe the world’s “first ecological civilisation” and has harkened back to Nazi language railing against “nomadic” (see: rootless cosmopolitan) people who “do not care about the environment” as “they have no homeland.” Further, National Rally party spokesperson and recently elected member of the European Parliament, Jordan Bardella, proclaimed “borders are the environment’s greatest ally; it is through them that we will save the planet.” Bardella has also espoused the ‘great replacement’ theory.

In a further sign that far right political parties are shifting on the issue of climate change, the youth wing of Alternative for Germany (AfD) have urged their party leaders to renounce the “difficult to understand statement that mankind does not influence the climate” as it is an issue which motivates “more people than we thought”. Whilst the AFD’s vote share grew marginally in this year’s European elections where they received 10.8 per cent of the vote, its increase paled in comparison to the Green Party’s surge to second place where they garnered more than 20 per cent of the vote in a country where climate change was many voters’ top concern.

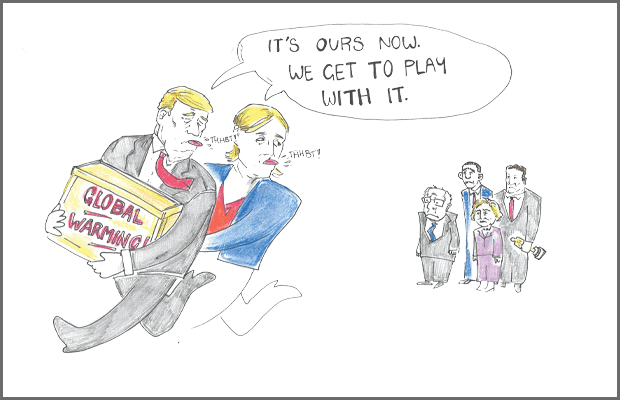

As the 2020 US election is beginning to heat up, there are even rumours that Donald Trump is attempting to go green, with the majority of Americans in favour of stronger environmental protections. David Banks, who previously advised Trump on environmental matters, told Bloomberg, “for the President to win these battleground states, he’s going to have to have some record of environmental achievement to showcase.”

The far right’s changing stance on climate change presents a clear challenge for progressives and leftists. Of course it is principally and politically imperative to explicitly reject the most heinous eco-fascist “blood and soil” sentiments, however, it is just as crucial to not let their arguments seep into genuine environmentalist movements, which have already formed in some sections of the so-called left, with arguments around population control and the supposed threat of mass migration often used.

More importantly however, it is incumbent on us to acknowledge that the liberal left has already been ceding ground to the right. For the past two decades, the climate debate has hinged upon climate denialism versus climate science, and the liberal left strategy has been simply to debate the right on their own terms (is anthropogenic climate change real?) and to convince the public of the science. Whilst this is certainly important, particularly given the power that right wing media organisations wield — especially in Murdoch’s Australia — it should never have been the sole or even primary strategy. Ultimately, this singular focus on attacking denialism has meant the liberal left has remained on the back-foot, ill-equipped to go toe-to-toe with the political right if and when it proposes harmful policy prescriptions concerning climate change. The majority of progressives and leftists alike have been defined by what they’re against (climate denialism, Adani, the Liberal Party), rather than what they’re for, failing to articulate a broader, cohesive political vision.

Denialism seems to be slowly on the way out, and it’s pertinent to ask whether the alt or far right will be able to influence the narrative. However, a cursory glance at Trump’s America should already give us the answer. Right wing populists such as Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon who teeter at the ethno-nationalist fringes of society have already been successful at importing their ideas into the White House. Moreover, as right wing populism and anti-immigration sentiment continues to grow in Europe, it isn’t difficult to imagine far right positions on climate change infiltrating climate policy. Where climate change and immigration were once viewed as discrete issues in the political sphere, taken up by the left and right respectively, it seems increasingly likely that more sections of the right will begin using climate change as an effective political tool to advocate for even more punitive immigration measures.

Currently, the liberal left is unprepared to deal with such a challenge, and the strategic choice for progressives to focus on climate denial has functionally depoliticised climate change and turned it into an intellectual contest of ideas, rather than a political fight over competing visions of our collective future.

Those on the left now have the opportunity to abandon denialism and scepticism as focal points, and instead analyse what the climate realists on the far right are doing. Pertinently, there is a desperate need to advocate a bold, just and transformative agenda. There are certainly interesting developments around what a Green New Deal would look like. Importantly, in grappling with Labor losing the unloseable election and decimating its vote in Queensland, sections of the Australian environment movement have recognised that green jobs must be a central demand in winning over workers and broadening the environmental movement beyond the #StopAdani #Resistance.

Ultimately, political leaders in the Global North can denounce El Paso and Christchurch and offer thoughts and prayers. But failing to both dramatically curb global warming and open borders to refugees in the face of migration spurred by climate change will in the end have far deadlier consequences than any 8chan eco-fascist with an assault rifle.