Women have always been present in the musical world, but they are seen far more than they are truly heard.

According to a recent report by UK classical music label Drama Musica’s DONNE: Women in Music, curated by soprano Gabriella Di Laccio, only 2.3 per cent of the works programmed by internationally acclaimed orchestras in the 2018-19 season were by female composers.

In classes analysing the history of classical music education, Clara Schumann is mentioned first as the companion of Robert Schumann, and second as a performer and composer in her own right. Hildegard of Bingen is often presented as a great standalone. Augusta Holmès, an extremely talented singer of the nineteenth century, accomplished pianist, prolific composer, was endlessly praised by Rossini, Liszt, and Saint-Saëns in her time, but is now mainly celebrated only on classical music radio stations on International Women’s Day.

There are legendary musical women behind the great composers—famous examples are Mozart’s sister, Nannerl, and Bach’s second wife, Anna Magdalena. There are several articles calling for the recognition of female composers, but one must ask whether these sudden and infrequent resuscitations of historical female composers really do much to change the situation in the long term. While female-only groups and festivals are often the only way female composers and performers can be heard, there must be another way to integrate female composers into the mainstream of education and performance. They should be considered as composers of worth and without consideration of gender, for it does not benefit composers to celebrate them for their femaleness instead of their musical talent.

Jazz is another main genre of institutionalised music study that shows extreme gender imbalances. A 2016 study of the top five American institutions of graduates in jazz study (University of North Texas, The New School, The New England Conservatory of Music, CUNY Queens College, and Berklee College of Music) found that only 17.5% of those students were female.

While it is far more common to see female classical musicians at the Conservatorium, the numbers remain comparatively low in the professional world. A 2018 study of the world’s top orchestras, including the Royal Concertgebouw, Berlin Philharmonic, and Vienna Philharmonic, found that only 31 per cent of 2438 full-time orchestra members were female. The Vienna Philharmonic had the highest imbalance—perhaps most audibly distinctive orchestra in the world, which jealousy protected its sound by maintaining the lineage of its players, the orchestra didn’t allow a woman to join until 1997. The London Philharmonic and New York Philharmonic are, to some relief, far closer to total equality.

As an attempt to reduce gender bias, orchestras in the 1970s began to incorporate blind auditions, at least in the early stages. However, the problem of gender imbalances in music is present long before auditions and professional exposure—it begins even when children choose their instruments.

Brass instruments have long been considered a ‘man’s instrument.’ Instruments with a low pitch range, such as double bass, are also considered more masculine than higher pitched instruments, like the flute or violin. Indeed, the same study found that only one of 103 trumpet players in 22 orchestras was female. 94 per cent of harpists were female. There was also a heavier concentration of women in flute and violin.

There is history to this: before and during the nineteenth century, women were discouraged from playing instruments that could potentially distort the face. Instruments thought to be ‘unlady-like’ when played, like the cello, or too heavy or powerful, like the tuba, were also deemed inappropriate for female musicians. Additionally, brass instruments were associated with the military, and the loudness and range of the instruments was thought to represent masculinity. Women were considered more suited to higher-range instruments with softer tone qualities as a result. Amateur training in singing and music, usually piano, was also considered the hallmark of an ‘accomplished’ woman.

In some respects, this mentality continues today: girls might find themselves encouraged to be vocalists rather than horn players, to play wind instruments rather than brass, and compelled to learn melodic instruments over percussion. It is not just the problem of how we perceive women in music now, and the often narrow opportunities they have, but that they are limited by societal norms before they even begin.

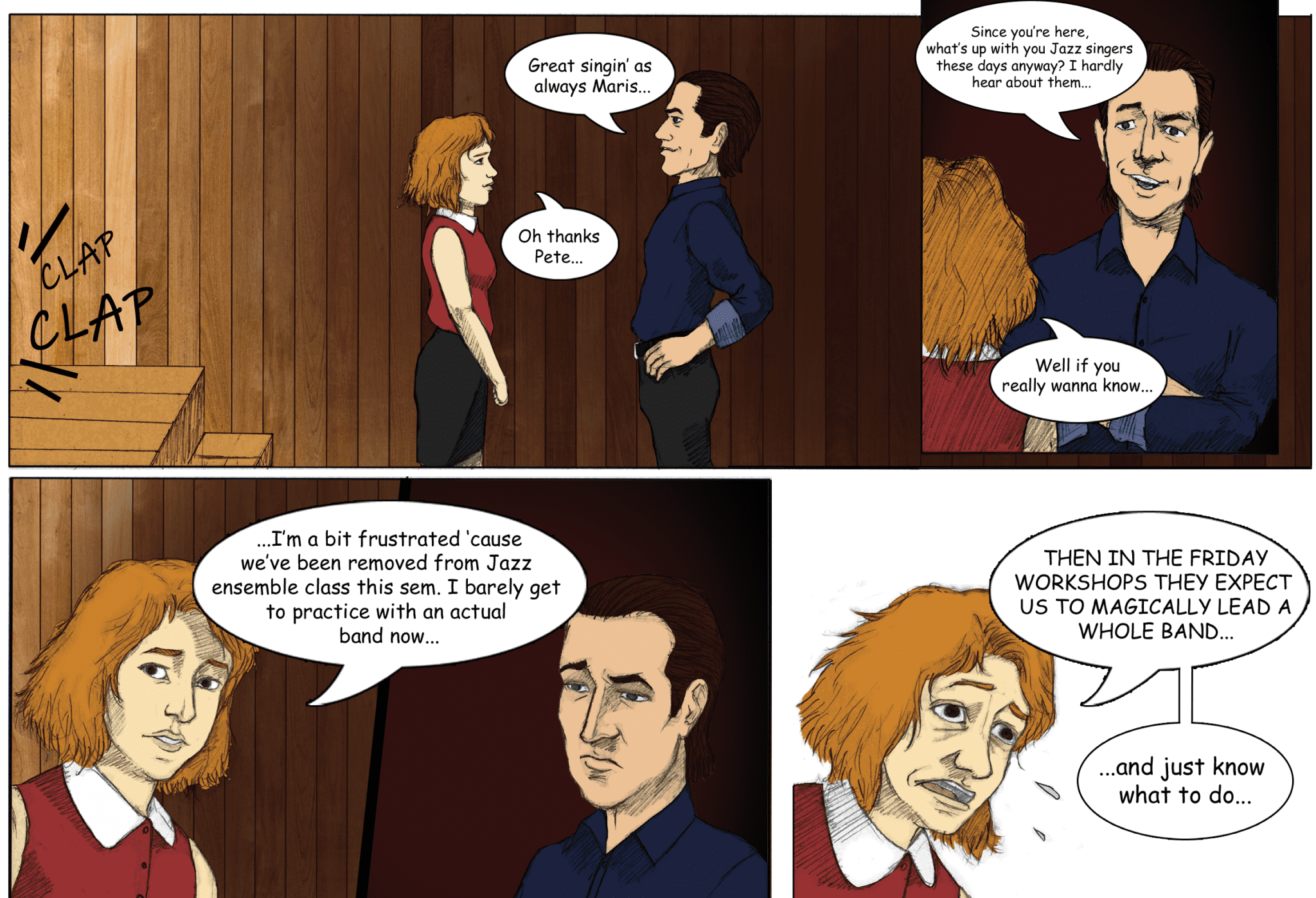

The ‘gendering’ of instruments applies equally to jazz. Women are very rarely on stage or, if they are, they’re typically a vocalist at the front of the band. It often seems exceptional for a woman to be a horn player or part of the rhythm section, perhaps with the exception of being a pianist.

In her article on professional female brass players, Mary Galime discusses how history perceives and remembers female players. She notes that with great trumpet players of history, such as Wynton Marsalis and Louis Armstrong, skills are highlighted quite beyond gender and more about quality: “All these novelties have transcended gender because history has allowed them to, but this has not been the case for female brass players.” While a gradual shift in mentality is currently underway, she says, with internationally respected musicians finally being appreciated for the music they are playing, and how they are playing, it is still typical that the players and the audience are constantly reminded that they are, in fact, female.

I spoke to Abby Constable, a drummer in the Jazz Performance degree at the Conservatorium, about whether she had ever felt limited in opportunities.

“In my experience I have no difficulties in being booked for gigs. If anything, I think some people are drawn towards the ‘novelty’ of a female drummer, and I could never be sure, but I think there are some gigs I may be more likely to get because of this fact. But this is honestly speculation. I wouldn’t want to get a gig because I’m female, I want it to be because they like my drumming.”

Often in musical situations where she is the only female present, she maintains that she experiences very little gender discrimination:

“99% of the musicians I have worked with have always treated me as a fellow musician the same as any other male on the bandstand. There has been only one situation in particular where I have felt quite uncomfortable and treated differently due to me being a young woman, and it was from an older male musician. I feel uncomfortable to speak out about it, also because I don’t want to lose work but I have said something in the past and he kind of brushed it off and laughed. In situations like those I am hyper aware of the fact that I am not a male.”

Like any other fields, most of what we have about the female experience in music rests in anecdotes. In popular jazz bars in Manhattan, I spoke to recent jazz graduates of the Juilliard School of Music, who told me about a particularly female-excluding phrase, “dick on the forehead swing.” They told me that they were often instructed during gigs to “play to the ladies.” I remember one night a very accomplished singer was invited to join the band. But after the rest of the band members did their solos, and she had made the return to the head of the song, she was interrupted by the sax player, who continued his solo over her voice. It wasn’t clear whether or not it was intentional, but she made a lighthearted face at the audience, who laughed. Afterwards, her responses to praise were self-deprecating even to my friend and me, when she asked us for a light outside.

I spoke to Tiana Young, a vocal student in the Conservatorium jazz program. She began classical training at age ten and started singing with the Central Coast Little Big Band at age fourteen. She talked to me about the differences between the classical and jazz performance worlds:

“From where I was in my training, classical was beautiful, polished, and elegant. I performed in concerts with orchestras and musicians who were poised, focused perfectionists. These concerts and competitions were serious affairs and the response to successful ones was equally formal, and somewhat reserved.”

“At the same time, my experience with jazz was highly different. To me the music was much more relatable, raw, sometimes sexy, and much less postured. The lyrics of the songs were emotional responses to personal experiences (from my perspective) and as such, audience connection always felt more raw and close. Performance spaces were smaller, more intimate, but the response to success in jazz always seemed huge and equally raw.”

“So as far as the negative experience, I have definitely had my fair share of sexualisation by older men in explicitly jazz musical contexts which is inappropriate in my ‘work environment’ but I feel that this is a product both of the male dominated space, and the raw, exposed nature of the medium: no boundaries, both literally — you’re right up with the audience — and metaphorically. This was present on the Central Coast where I grew up, Sydney, and Germany so I’d say it’s safe to describe that as a fairly universal experience.”

On being a woman in a male dominated space, she said: “I still have to remind myself that my voice as a vocalist and as a woman is just as important as the boys” and that “in an ideal setting a woman should be able to be as sexy or not sexy as she wants and not get treated as an object or as inferior…But unfortunately lines become blurred and because it’s such a ‘chill’ genre, perhaps compared at first glance to classical, I find that people push buttons a lot more.”

It’s common in jazz for improvised solos to be competitive and to ‘cut’ other players. I asked her about this, and she said: “Yeah, but guys have the privileged position to take the heat, whereas us chicks are sometimes already 10 feet behind.”

Steph Russell, a recent vocal graduate of the jazz program, offered another perspective.

“Yes, I think singers are always treated differently to instrumentalists, but I think it’s hard to be treated the same. We just have completely different outlets for our creativity and we prioritise different things, such as lyrics, feeling and performance.”

On the increasing awareness of women in jazz, she said: “From my first day at uni to my last day, I saw a big shift in the way I was treated, slowly becoming less intimidated and more comfortable within myself as well, which is a big factor. And in terms of the female to male ratio I don’t really mind which gender I play with, whoever I find the most enjoyable to play with and the most friendly — that’s who I’ll book.”

“And one great aspect about being the singer: we get to choose the band 90% of the time.”

Whatever the individual skill of a female jazz singer, she is often sexualised for her image rather than appreciated for her knowledge. An academic article by Stang Dahl in 1964 referred to female jazz singers as the ‘canary’ of a band — an appealing female vocalist could attract greater audiences and promote the bands while bringing business to the venue. Musically, the role of the singer was to interpret and convey the lyrics, not to improvise, and since improvising is a hallmark of jazz, this would create a ranking between the members.

There is no doubt about the skill and talent of famed singers throughout history, like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday, which seemed to transcend that fact that they were female. Front of the band, the ‘First Lady of Song’ and ‘Lady Day,’ and several other vocalists, were pioneering figures. An entire generation of famous jazz musicians can be linked back to one woman: Mary Lou Williams, a pianist of the 1920s, 30s and 40s. An exceptionally skilled performer, she also wrote hundreds of songs for Duke Ellington, and helped train household names like Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and Dizzy Gillespie. While she is not totally forgotten, such women seem to stand alone in history as exceptions and not part of the norm.

A woman of colour in jazz would have also faced far greater disadvantages — although jazz came from African-American communities in New Orleans, women were still excluded. It wasn’t until the peak of the women’s suffrage movement in the 1920s, and the development of the liberated ‘Jazz Age’ woman figure, that women began to be recognised in jazz communities. Bessie Smith, for instance, was an early vocalist that inspired later generations of jazz singers. Several female jazz musicians were activists for gender or racial equality, often both. In 1964, Nina Simone performed at Carnegie Hall to an all-white audience. She sang ‘Mississippi Goddam,’ a song about the racial injustices of African-Americans in Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. Another instance of jazz aligning with the Civil Rights Movement, happening at the same time, was Billie Holiday’s song ‘Strange Fruit,’ a disturbed vision of lynching:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

In this sense, jazz became a platform with great potential to express both gender and race issues, and continues to have that potential. In October 2018, Berklee launched the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice. The website states:

“The jazz industry remains predominantly male due to a biased system, imposing a significant toll on those who aspire to work in it…The goal of the Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice is to do corrective work and modify the way jazz is perceived and presented, so that the future of jazz looks different than its past without rendering invisible many of the art form’s creative contributors.”

‘Institute’ is key — by sincerely studying women’s contributions to jazz history as part of an institution, alongside female educators, we are far more likely to see permanent change. Without any question of talent, it is hard to deny that female musicians have to work much harder to prove themselves in an environment that has adapted to benefit men. In the past, female groups would have been the only platform for female musicians to perform music. A group like Sydney’s Young Women’s Jazz Orchestra is valuable in that it alerts us to new ideas, rejects that certain types of music can only be performed well by men, and sets up the path for new young musicians, but still there is the problem of being on the sidelines. As Galime says, there is a fine line between possessing “a quality that brings meaning and is remembered” and being a novelty item that is “cheaply bought, and momentarily appreciated.”

What music of all genres needs is a platform where female composers and musicians are granted the same institutional respect as males. It is not enough to have brief moments of respect for female musicians — this quickly becomes a matter of simply being female rather than focusing on the merits of their music, and this is more detrimental in the long run to true cultural appreciation of women. Sometimes we are hopeful about the situation, and told that “things are getting better.” But it hardly means much when some of the greatest institutions of jazz, such as New York’s Jazz at Lincoln Centre, still have no permanently employed women in the band. Emma Grace Stephenson, a jazz pianist currently living in New York, put it simply in a 2017 blog post:

“I get some opportunities because I am a young female, and reasonably good at what I do AND there are some opportunities that I don’t get, because I am a young female, despite being reasonably good at what I do.”

It is a difficult situation to navigate: on the one hand, women are evidently excluded from institutions of music, but also most women would not want to be given the opportunity simply because they are women. It will always be better to be known simply as a great musician than a great female musician. The canon of Western male composers is cemented in classical music culture already but what we can change is the gendering of instruments, the balance of the sexes on stage, how we look at history, and perhaps most importantly, becoming undoubtedly skilled in whatever instrument in whichever genre of music. Women need to be incorporated into the mainstream of study and performance so that the quality and respect of their work transcends gender. Change begins with our institutions, so that a world of music that transcends gender is the one to be canonised in future history.