Before getting into an article that puts racism under a microscope, I’d like to acknowledge that the writing and publication of this article took place on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. Sovereignty was never ceded, not in 1788 when the First Fleet began its violent conquest of this land, and certainly not now when this University has a building and statue dedicated to the coloniser William Charles Wentworth. This acknowledgement will mean nothing unless we make active efforts of decolonisation in our lives. Always was, always will be Aboriginal land.

It’s really hard to talk critically about racism in communities of colour. In some ways, it feels like a betrayal to suggest that we could be willing participants in our own oppression. However, if there is anything that I have learned since entering the political maelstrom of the University of Sydney (USyd), it is that people of colour are not as immune to perpetuating racism and white supremacy as we may think.

I have no shortage of childhood anecdotes that are fraught with innocuous racial prejudice. My parents are Chinese immigrants, and I was born here in Australia. I remember laughing when my white friends would jokingly pull at the corners of their eyes in exaggerated mimicry of my own. Sometimes I would copy them, much to their uproarious laughter. I thought that because they were my friends, they could not be racist or mean any harm by their remarks. I forgave them out of the pure virtue of friendship.

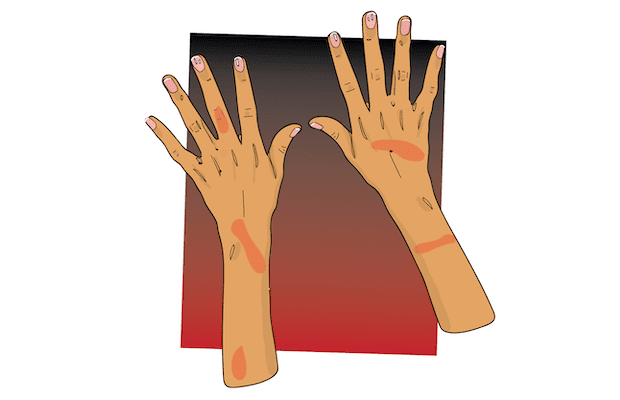

My own internalised whiteness became painfully and starkly apparent to me when I was asked for my Chinese name the other day and I came up completely empty-handed. I must have pondered it for hours, reaching desperately for three characters that should be as familiar to me as the lines of my hands. Like most forgotten memories, the more I tried to remember, the more it slipped away. The hatred that I had for my mother tongue as a child leaves a dark mark on everything I do, even now.

These stories of shame are just two of many that I keep stored away in the back of my mind. They reveal to me the two common misconceptions or ‘untruths’ that uphold the popular belief that ‘colour’ and racism are mutually exclusive.

First, that racism is the intentional discrimination based on a hateful prejudice against people of colour. The racism that I’ve encountered from childhood through to student politics has rarely been this simplistic. Racism is intrinsic to living in a Western world that places a post-racial blindfold over our eyes and tells us that we have multicultural harmony. We’re all familiar with the violent colonial narratives that have resulted in the world we live in. Our biggest mistake is assuming that this history is not still being carried out. Racism on a micro-level comes out in forms of microaggressions and stereotypes that are often deemed too unimportant to call out for what they are. Thus, these incarnations of racism survive.

Second, that the term ‘people of colour’ is inclusive and progressive.

Uses of the term ‘people of colour’ or PoC can render us as homogenous and erase the unique struggles faced by people of all different ethno-cultural backgrounds. This world is fractured immeasurably by race, not simply halved by polar opposites of whiteness and colour. My experience of racism is different to the person next to me. Additionally, this is not a term that was born in this country; it comes from the United States and brings with it a host of different racial politics, histories and traumas. We should be carefully examining our use of this term in Australia in the first place, as we should with all transplanted ideologies.

People of colour can and do uphold racist structures. There exists the presumptions that Chinese people are dishonest, that Latinx people are inherently associated with the drug trade, that Brown people are terrorists, that First Nations people are uncivilised. While we often think that these sentiments are reserved for our white oppressors, they absolutely are not.

I am the eldest daughter of Chinese immigrants, but I am not proud of the anti-blackness that permeates my mother culture. East Asian beauty standards are notorious for their paleness; my limited cultural understanding of this is that historically, darker skin tones indicate more time spent outdoors doing peasant labour. I have had friends, also of East Asian background, jokingly call me Cambodian for my tanned complexion, a far cry from the snow white complexions that are plastered across the billboards of Guangzhou – my parents’ home city across the sea. So, whether I like it or not, there is a form of racial supremacy that has made my body its playground. Its covert presence manifests in colourism – prejudice against darker skin tones and the Trojan Horse of white supremacy in communities of colour. It is disguised as a gift, as a ploy to poison us from within. I have often felt like even my body isn’t my own, that I can’t lay claim to the Chinese identity if I don’t fit comfortably into the form that it has designated for me.

When my father speaks, I have often noticed a certain green-eyed possessiveness tinge the air around us. His racial prejudice is not limited to anti-blackness; upon realising a bad driver is East Asian, he changes the tune of his argument: “New Chinese immigrants bring all their bad driving habits here and ruin our roads.” This is absolutely not something that you would expect coming from the mouth of a Chinese immigrant who has lived in this country for thirty-odd years. I tell him this. His reply is: “I’m different. I’ve been here for 30 years and I have always respected the culture of this country.”

My father’s xenophobia leads me to wonder why certain immigrants are so spitefully hostile to others. I arrive at this hypothesis: though I come from a low socio-economic background, and my family communicate in a discordant mixture of Cantonese and English, we are a part of an immigrant class that possess a certain upward mobility into a white society. This upward mobility leads to the formation of an immigrant ‘underclass’, a group that is both different and worse-off than us. As an Asian-Australian, I find myself as part of a ‘model minority’, put on a pedestal by the West in order to keep other ‘inconvenient’ immigrants in line and subjugated. Our perceived position as ‘good immigrants’ is used to drive wedges between different communities of colour. Perhaps the reason that this model minority myth has been allowed to survive for so long is because of the untruth that engenders a homogenous ‘people of colour’.

Let’s unpack this idea of a model minority. On first glance, many people have made a broad range of assumptions about me: that I am good at maths, excel in piano or violin, excel academically, and that one day I will be a doctor, lawyer, dentist, or prominent businessperson. As a woman, it is assumed that I am quiet, dutiful, and graceful. It is assumed that we keep our heads down, eyes averted and mouths shut. This is ideal for the prism structure of white supremacy that thrives off silence and uses it to create illusions of multiculturalism and harmony. Our perceived submission and assimilation into society is something that Western powers want to replicate in all minorities.

Don’t get me wrong, my experience as an Asian-Australian is not easy, especially at this University. Recent waves of Sinophobia on campus have made me feel terrified to live in my own skin. Several incidents come to mind: on the first day of this semester, a Chinese international student was assaulted on the stairs leading up to City Road. On the first day back from the mid-semester break, Asian students faced disgusting sinophobic slurs from a man outside the Wentworth Building. During campaigning for the SRC elections, presidential candidate Josie Jakovac was accused of verbally harassing a Chinese campaigner for speaking in Mandarin to another campaigner and upon realising her mistake, did not apologise for her hurtful presumptions. Despite these atrocious sinophobic incidents that have occurred too close to home and heart, my life has been far easier than many. This is because as a ‘model minority’, Asian-Australians have been deemed to contribute to society (through cultural avenues such as popular culture, cuisine, fashion) more than the aforementioned (implicitly non-white) immigrants that are assumed to “not work, commit crimes, and bring their war with them”.

My father’s possessiveness of Australia stems from a deep-seated colonial legacy which places white-tinted lenses over his eyes. Australia, like all other offshoots of European colonialism, has historically painted a grandiose portrait of itself as a golden land of exciting opportunity, multiculturalism and harmony. I am conflicted about the way that racism has rooted itself into the immigrant heart. On the one hand, my father views immigrants of any sort as a threat to this false golden land. On the other, despite his many flaws, my father has also often expressed his sorrow for the struggles of First Nations people in this country. And despite the way that Chinese culture is inextricably intertwined with the hegemonic white traditions of the West, I know that my father loves his motherland, and the centuries of tradition and culture that it is built upon. The internalisation of whiteness comes from a place I can understand; a place yearning to belong.

Before I first stepped foot into this University two years ago, the idea of internalised racism and where it comes from had seldom crossed my mind (a testament to my privilege in itself). For all its flaws – arguably because of them – this University opened my eyes to the intricate machinations of race in political arenas. Being politically active – especially during the recent 2019 SRC elections when the student body saw the conservative Liberal-backed brand Boost make a grab for the presidency – made me think long and hard about the way that race operates in conservative politics. I’m referring, in particular, to conversative political figures such as British Home Secretary Priti Patel. I name and shame her specifically because I was recently sent a video of Patel on Twitter where she promised to “end the free movement of people once and for all”. In her spiel condemning implicitly non-white migrants, she also ironically criticises the “North London metropolitan elite” whilst conveniently leaving out the fact that she was born in Islington and is still a part of the racist ruling class that she calls out. Patel also uses the fact that her parents are Ugandan-Indian immigrants to ward off any possible backlash of racist sentiment. She tells us: “this daughter of immigrants needs no lectures”. Her smug, smiling face fills the screen as she pauses, inviting applause from a very white audience that thrives off the British colonial legacy that has oppressed (and continues to oppress) the people of her motherland. Watching that video made me sick to my stomach.

If there is one takeaway from this article, let it be that racism isn’t a white thing. It’s an everyone thing. I have lost my own name in the name of assimilation. I have lost my mother tongue, I have lost the ability to love of my own culture. We are never going to be able to weed out racism if we can’t even confront it within ourselves, starting with the aforementioned untruths of racism. While the colour of our skin gives some of us a unique vantage point from which to examine race, in a grand twist of irony, it can also blind us to our own racial prejudices and internalised whiteness. As the daughter of Chinese immigrants, one who possesses certain privileges of access, safety, and ability, I am responsible for educating myself on the way that race shapes our lives in tandem with gender, class and other lines of intersectionality. To rework the words of the inimitable civil rights activist and writer Audre Lorde: ‘I am not free while any person is unfree, even when their shackles are very different from my own.’