Matt Poll is the curator of Indigenous Heritage collections at the University of Sydney, as well as its Repatriation Project Officer. We talked to him earlier this month about the politics of museums, repatriation and an exciting new exhibition opening later this year.

Honi Soit: Hi Matt, thanks for your time. Could you briefly explain your role within Sydney University Museums?

Matt Poll: For the past decade or so I’ve worked as the curator of the Indigenous Heritage collections, as well as being the University’s Repatriation Project Officer. It’s been a pretty steep learning curve, but my job is basically to be at the intersection between the Aboriginal community and the history of the Museum collections. I was pretty lucky, I came from Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Cooperative before that: a lot of my background has involved documenting histories and building community stories into objects and artworks and things like that. I guess my official role is to curate the collections, but also it’s been pretty important to keep track of the shifting landscape. More communities are becoming interested in collections and assessing what they mean and what they can mean. Rather than sitting there as old museum ‘objects’, people are increasingly using them in the construction of their modern identities, and empowering themselves by writing new histories.

HS: As well as your role as curator of the Indigenous Heritage Collections, you’re also the University of Sydney Repatriation Project Officer. How does your experience working in repatriation inform your curatorial practice?

MP: It’s pretty confronting. There’s a lot of cultural safety involved, which isn’t something that’s really written into the position description, so you sort of learn those things amongst your own networks. How to take a break, community naturally have really strong reactions and emotions. Ancestral remains repatriation is basically organising someone’s funeral, but it’s all organised by strangers. All sorts of things can come into play. Sometimes they’re really beautiful and special ceremonies, you see divisions in the community fading away. There’s a lot of disbelief until it actually happens, so that’s my role, to keep reassuring people that you’ve got the law on your side. If communities want these remains back, it’s mandated by the United Nations International Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People that these are yours. Museums can’t tell Indigenous people what to do with them anymore. I think so many of these, especially South Eastern Australian communities, have been disempowered for so long that when you have that power you have to learn how to exercise it.

HS: The opening of the Chau Chak Wing Museum (CCWM) will provide an opportunity for many more works within the University collections to be accessible to the public. What’s your process for exhibiting items with respect and sensitivity?

MP: Listening, letting the community be the curator. Anyone who has looked at the explosion of contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art in recent decades knows that these days it’s crucial to be transparent, inclusive and participatory in the way that cultures are represented in museums. Creating a space for First Nations communities to write their own histories on their own terms. Sometimes it feels you have to fight for being so proactive and inclusive and embedding people’s voices in the selection of the objects. Not all cultural objects have the same protocols as Aboriginal collections in Australian museums do. A lot of the criticism of the British Museum by Aboriginal activists is not over the ownership, but more so the way that the objects are interpreted. I think that’s slowly influencing the thinking of other curators and curatorial departments. Learning from what’s happening in Aboriginal collections in Australian museums is hopefully offering templates for other First Nations cultures around the world to use their activism and resistance as an art form in itself.

HS: How have you consulted and collaborated with Indigenous communities while preparing for the opening of the new museum?

MP: The interesting thing about consultations is that a lot of the communities that we have repatriated objects to are actually the same communities that we are going back to now to consult about other objects which weren’t repatriated. Having done that repatriation, you have built a little bit of a bridge to have a new conversation. You get all sorts of responses, too. A couple of exhibitions we proposed, the community said no to, so we put them on the shelf for later, when they may want to do them on their own terms. It’s just about being open and accepting of being told ‘no’. That’s actually the key to all the community and consultation work I do. If someone says no, or if someone’s really angry, that’s not the end of the world. That’s what being a curator and engaging ethically with Indigenous people is all about actually; not representing the museum but being aware of the reasons why some people distrust museums. Being prepared to have difficult conversations about the past is 99% of the job.

HS: Tell us about the exhibition ‘Ambassadors’ that will feature in the Chau Chak Wing Museum.

MP: It’s come out of 20 years of conversations for me. I’ve been incredibly lucky like that, from working as a volunteer and up through the lowly paid sections of the arts (laughs). The arts isn’t a very inclusive environment for anyone in some sections, but that can be more so for Indigenous people. There’s a lot of proactive and inclusive programs that get people in, but you don’t see those really being sustained so it’s just been a little bit of luck and persistence to build my own networks. When it came time to present, especially these problematic collections, from the anthropology department all sorts of issues arise. The assimilation policy in Australia was implemented by some anthropologists who were trained at the University of Sydney. For much of the early twentieth century the University was alive with all sorts of unethical ‘theories of race’ and pseudo scientific garbage that entangled Aboriginal people’s everyday lives. The University trained these people in the same way the University still trains law students who may go on to oppose Native Title applicants. You just need to look at the Ramsay Centre debate from last year to see how many sections of the broader society really do see universities as machines of social transformation. So when we say museums are not neutral — universities are not neutral either.

It was not that I expected any pushback. It was actually a bit of a really amazing intersection of what I was noticing happening in museums overseas and especially around the country with other curators and networks here in Australia. In the sense that, you can say that you’re doing consultation but how do you show it?

So Ambassadors is actually an exhibition in which the whole curatorial philosophy is just to show the consultation process in the way that the exhibition spaces are curated. In an ideal sense, as a curator there will be nothing of my voice or that sort of old-fashioned ‘experty’ thinking being injected into it. It will literally be an interpretive layer completely authored by the contemporary community from the communities who have the right to speak on behalf of these objects. That’s the whole goal of the show and it’s been hard, and you get a lot of pushback in some things, especially when people want to bring their own ideas to these objects. But that’s what I hope will be the most exciting part of the show, for people to actually engage with the contemporary voice of all these diverse communities around the country, because there never was this homogenous Aboriginal Australia, and that’s the other goal as well.

HS: So it’s like you’ve given a lot of agency back to the communities where these objects have come from.

MP: Entirely. There are still limitations and logistics involved — someone in 50 years will be working with these objects as well. You can’t put community members in these dangerous positions of making rash decisions about these collections either. It’s been a learning process for me, which is what I’ve tried to keep doing, because you’re always learning.

HS: Will Ambassadors be a single exhibition in a space, or will it be interspersed throughout the museum?

MP: Definitely interspersed. There are different configurations of the show as it evolves, in another 2 years time or 5 years time as we bring in more voices and hopefully some more staff. We could have a whole team of PhD students working with this collection for the next 20 years. If anything, this is a little bit of a showcase, a tip of the iceberg and a starting point for all community members who would like to explore not just the collections, but the University’s role in constructing this image of Aborginal Australia, which for a long time was entirely authored by non-Indigenous people, and that the University still profits from in some ways.

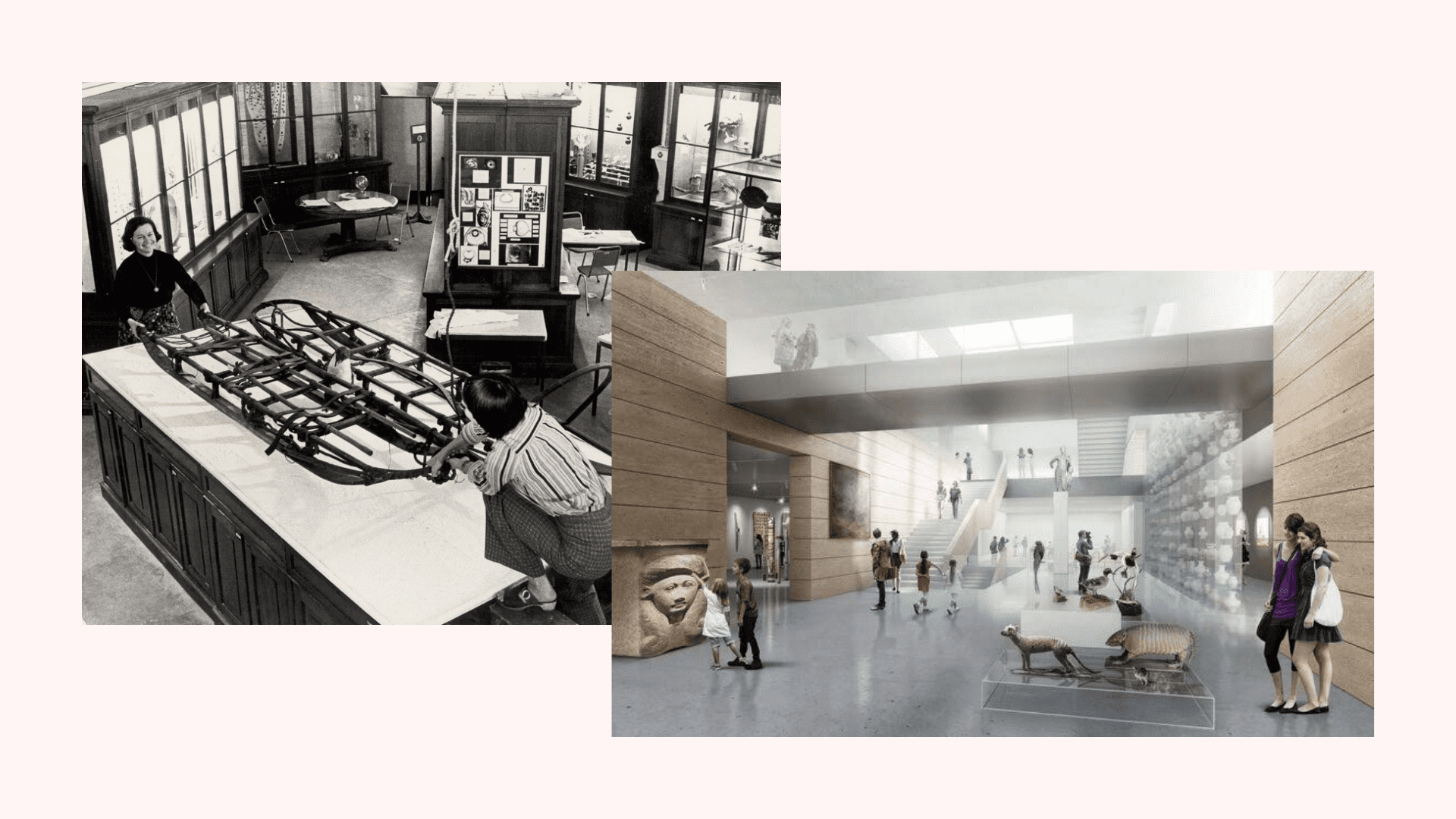

Artist’s impression of the Chau Chak Wing museum. Image: University of Sydney

HS: Do you think that there is room within the exhibition to acknowledge the University’s role in ongoing colonisation, or are there limits in it being a University museum?

MP: No, being a University museum that actively engages in research and teaching is actually a little more experimental than the stereotypical 19th century museum that is being left behind. Australian museums in the past were informed European collections which come out of royal families and old kingdoms – these are just so anathematic to what museums in Australia are about today. It shows you the way Australian museums are going towards a different model which is more philanthropic and university teaching focused. It’s not only the ambassadors, each of the permanent spaces is actually connected to an embassy, and that the embassy is a remote art centre. Remote art centres are the front doors for all communities, but they’re also sometimes the only spaces that are putting cash in the most economically marginalised people in the country’s hands. Millions of dollars are poured into government resources to these remote communities and homelands but you just don’t see it when you visit them. Whereas art centres are that interface where people can practice culture and actually be recognised for it in real time. But that’s the difference between museums and art centres and art galleries too, they’re very different worlds. If anything, it’s breaking down those rigid, older ideas of what museums or galleries should be doing, because when you talk to communities, they don’t care either way if it’s a museum or a gallery.

HS: Have you found that there’s a little bit of a tension between drawing from the collections of the Macleay museum, which was quite old fashioned in its display, and what you’re doing with Ambassadors?

MP: One positive thing is that we’ve completely left behind that nineteenth century museology, which from many in the community just looks like cultural taxidermy. You could not really do the Ambassadors consultations in the old museum space because people would react to the space first. The architecture of the space — natural history museums all come from this idea of Noah’s Ark being upturned by all the animals two by two. There’s not just themes of colonialism in museums, there can also be elements of Christianity which can be really not that obvious, but they are there when you really unpack them properly. But that’s also where exciting transformations can happen — take natural history museums, the CCWM is actively renaming the native species of animals represented in the collections in the Aboriginal languages from where they are associated with. Kangaroos from Wiradjuri country can be renamed alongside kangaroos from Bundjulung country, the trade networks that can be discovered through similarities between language words is just one more of the really exciting things that is happening too. To have this new twenty-first century space, which is a little bit more adaptable, it’s a much more fluid space where we can actually bring in people from all those embassies too, to work on the education program or to use the new auditorium for the public program. We’ve been so focused on the exhibitions up until the opening day, but we’ve also got to do a lot of work after we open as well. So that’s also where we’ve built in the embassies, to bring in community members associated with these collections and let them bring their interpretive layer right into the way the exhibitions are presented to the public.

HS: Could you take us through the process of contacting and collaborating with the communities that these objects belong to?

MP: Surprisingly there is a lot of documentation that has sometimes been lost over a couple of generations between the makers of these objects and their contemporary descendents. For example, I’m also working on the big Yolngu exhibition, which is separate to the Ambassadors exhibition, but for that one, that’s one of the most successful art centres of Australia, if not the whole Oceania region. It’s not a missing layer of their history, it’s just one that because of that tiny old museum space we used to show one or two of their paintings at a time, whereas now we’re showing all 78, and how they actually connect together through the songline stories that they’re mapping and things like that. So to actually have the space to properly show these objects back to the community is really important. One of the things I’ve learned is that a lot of the makers of these objects actually wanted them to be — their agency is important as makers of these objects. Which is why you don’t hide the critical aspect of how they were collected too, through anthropology. Even in the assimilation era, people were still finding any way they could to put their story on the world stage,recorded for posterity, and museum objects were just one way some community members found a way to do that. There’s nothing more exciting as a curator than when you see a descendant see an object that they know of, but haven’t actually seen, and can actually read it for two hours in language and sing songs associated with it and interpret it in a completely different way than we have as museum curators. That’s pretty well the goal, really — to reconnect those objects. The longer exhibition title was originally Objects as Ancestors, but I thought it was more important to stick with the diplomatic aspect. They’re ambassadors, and they’re embassies, and they’re ambassadors of lots of different nations across the country.

Artist’s impression of the Chau Chak Wing museum. Image: University of Sydney

HS: Will there be another permanent exhibition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art and history, besides Ambassadors?

MP: There will always be at least nine permanent exhibition spaces, and the Macleay and Nicholson technically dissolve as well to become the Chau Chak Wing Museum. Which is another story, and we’ve had interesting responses to that as we face the twenty-first century and Australia’s place in the Global South as part of Asia. In any case, I can’t imagine any museum in Australia in this day and age wouldn’t put Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture up front in permanent spaces. International audiences, when they come to Sydney don’t especially want to see convict watercolours, they want to engage with contemporary Aboriginal Australia. A couple of our ambassadors are actually in other exhibition spaces, so we’re invading their space, a reverse colonisation, if I can put it that way. How the exhibitions and collections consultations reconfigures itself in the future will be based on the audience reaction to it over the next couple of years.

HS: Housing all of the University museums under one roof allows for new ways for the collections to interact. How will the Indigenous Heritage collections interact with other collections?

MP: Looking at these contemporaneous civilisations from 3000 years ago and looking at the commonalities rather than the stereotypes. You want to see Baru, the crocodile ancestor in Yolngu country in conversation with ancient Egyptian crocodile ancestor, Sobek. Both civilisations were contemporaneous in time 3000 BP and shared a common knowledge of the crocodile, albeit transforming this knowledge in entirely different ways. But you don’t want to force that conversation. There is also so much work to do with representing Aboriginal culture to Chinese audiences and vice versa. There was that awesome Benjamin Law documentary earlier this year where he was exploring that for 700 years Macassan traders were in the northern parts of the country selling trepang through 14 ports all the way to Canton in China. In my own experience of taking international students on trade groups, there’s no awareness of Australian history, let alone the uniqueness of Aboriginal Australia. To be able to break down those barriers for Asian audiences in general is really exciting. You look at the success of White Rabbit representing Chinese contemporary art in Sydney —it just makes you realise there’s just a complete lack of representation of Asian, African, South American and Pacific communities in general in Australian museums. Museums are still homogeneously ‘white’ in the sense of the audiences that they cater to. To be able to present these exhibitions for the non dominant audiences is one of my own real personal goals. You find so many more interesting understandings of what these collections might mean.

The CCWM collections are exhaustively interconnected — if you look at the natural history collections, or even the scientific instrument collections. They can be explored in far better intersectional contexts than just as collections themselves . If you look at the scientific construction of race, how tools such as photography and statistical aggregation were used as anthropometric tools to measure Aboriginal people,- construct versions of their past which trapped contemporary people in the past.

Photography was a tool used to classify First Nations people from all around the world. That’s where the old Macleay’s natural history, science, photography and First Nations collections can be curated by Indigenous artists, historians and scientists in much more challenging ways than were possible in the old museum space. The more collection exists out there in the community, the more real it becomes as a conduit between the contemporary Aboriginal community and a version of the Aboriginal past that was written by nonIndigenous people associated with the University. Some of the feedback we’ve received from the community has been astounding. It’s the type of stuff as a curator that you’d spend hours trying to come up with, but in the hands of the community the simple feedback of “no this goes next to that because of that”, saves all the trouble of inventing a reason why. Through the consultations numerous collection records have been updated, not only to reflect the languages of the maker but what people expect to see when they see these things on public display and why some things they just don’t want on public display. As a curator it is always crucial to be able to actually listen and coherently repeat the messages that the communities that you are working with and representing through exhibitions such as these.

HS: From the names of its buildings to the origins of its collections, the University of Sydney has an uncomfortable relationship with its role in the ongoing colonisation of Australia. Has this informed the construction of the new museum and its exhibitions?

MP: It definitely has. You can’t work with the anthropology department for example and not know the histories that they represent. Internationally, activism in universities and museums has been gearing up since 2015 — the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, to BP or not to BP — a protest group which was incredibly successful in promoting the story of Rodney Kelly and his claim to repatriate the Gweagal shield acquired by Cook in 1770 on the same platform as the Greek request for the Parthenon marbles. All faculties at the University still today play some part in the transformation of Aboriginal land into the wealth of the Australian nation although many staff work hard to change this. It is the role of museums such as CCWM to counteract this narrative of colonisation of the Aboriginal past, to actively privilege the voices of sections of the community who are most impacted by the ways that museum exhibitions represent their culture on the world stage. These conversations that decolonisation is a new thing to Australia, I don’t really buy into that. They’ve sort of forgotten what was done by Edward Said in the 1980’s and all the activists throughout history who put their lives on the line to radically decolonise parts of the world such as India and parts on continental Africa. Even though we’re still quite slow to catch up on that sort of thinking, there are amazing people out there in the museums, galleries and libraries who are refusing to accept that things can’t be done differently and better in relation to the way the Aboriginal past is represented in spaces such as the new CCWM.

Ambassadors opens in the new Chau Chak Wing museum later this year.