“Are you religious?”

“Nah, I was a Muslim up until I was like 13 though.”

“Why did you stop?”

“I realised I was gay.”

They laugh and I join in until I realise that my trauma was the punchline.

But there’s a grain of truth in every joke.

One of the main reasons I left Islam was because I couldn’t handle the internal battle between faith and desire.

Did I even have a choice?

My relationship with Islam is complex. I don’t eat pork, I fasted during Ramadan up until last year, I pray when things get tough and I majored in Arabic in order to read the Qur’an.

Yet, I definitely drink, I don’t pray five times a day, I have premarital sex (sorry mum) and I can’t remember the last time I opened, let alone read, the Qur’an.

I didn’t have a choice, right?

So Let It Be Written, So Let It Be Done

When the question of whether queerness is compatible with Islam arises, conversations inevitably turn to the attacks committed against gender and sexual minorities in Muslim majority countries. A 2013 Pew Research Centre poll revealed the percentage of people in Muslim majority countries who oppose the social acceptance of homosexuality: Jordan (97%), Egypt (95%), Indonesia (93%) and Pakistan (87%).

Numerous Islamic leaders have publically condemned homosexuality, the Chairman of the International Union of Muslim Scholars, Yusuf al-Qaradawi, once stating that, “the spread of this depraved practice in a society disrupts the natural life pattern and makes those who practice it slaves to their lusts, depriving them of decent taste, decent morals and a decent manner of living.” During Australia’s recent marriage equality debates, President of the Australian National Imams Council Sheikh Shady Alsuleiman stated that, “we oppose same-sex marriage and consider it a sin and religiously illegal… Islam promotes equality; however equality itself has limits.”

While there are systemic problems within the Islamic community regarding the acceptance of queerness, it is also important to interrogate what Islamic scripture actually says about homosexuality. Discourse surrounding homosexuality and its prohibition in Islam is based on the story of Prophet Lut, which condemns violent sexuality and criticises men for leaving their wives in order to rape men.

However, contemporary scholars such as Amreen Jamal are calling for a critical rethink of the standard interpretation of Lut. Jamal argues that the story does not render a judgement against same-sex sexuality, as the objections towards same sex-attractions are on par with the objections towards opposite sex and non-sexual indiscretions alike.

This calls into question the ambiguous terminology used in the narrative such as “those not producing” or “men who have no wiles with women”, which can be interpreted as referring to eunuchs or impotent men. Islamic studies scholar Scott Kugle argues that the main focus of this narrative is therefore not about defining a “correct gender” for a man’s sexual orientation, but rather, preaching that both men and women deserve protection from rape and humiliation.

My Jihad

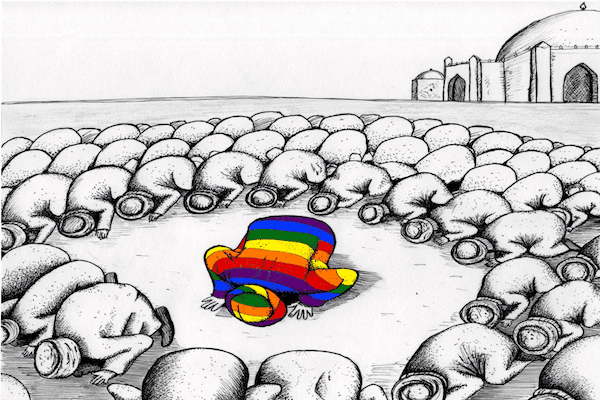

In a study on British Muslim gay men, one participant stated that his queerness was his jihad (struggle). Another stated that, “if I could choose, I wouldn’t be gay. I know I’m going to hell for this. I feel really ashamed, not comfortable or happy in my life….like my worlds are clashing.”

These statements encapsulate the internal battles encountered by many queer Muslims who are afraid of being ostracised from their own religious communities. Psychologist Rusi Jaspal explains this dilemma, arguing that “the social representations of homosexuality within these communities may be stigmatising, potentially resulting in a decreased willingness to come out and a perceived conflict between their sexual and ethno-religious identities.”

For many queer Muslims, giving into religious or cultural pressures, such as heterosexual marriage, appears to be the only method open to them to avoid otherisation.

The Muslim Closet

Queer Muslims attacked within their own communities for their queerness, and face homophobia and Islamaphobia in broader Australian society as well.

In 2007 in Camden, pigs’ heads adorned with the Australian flag were placed at a site proposed for an Islamic school. In 2014 in Bendigo, a protester shouted outside a mosque, “if you’re Muslim and you want a mosque, go back to the Middle East. This is Australia”. In 2017 at a Q Society fundraising dinner, Larry Pickering said that if Muslims “are on the same street as me, I start shaking….they are not all bad, they do chuck ‘pillow biters’ [a homophobic slur] off of buildings”.

Increasingly, far-right politicians use disingenuous concern for the queer community as a justification for anti-Muslim and anti-immigration policies. During the 2016 US Presidential race, for example, Donald Trump cargued that “Hillary Clinton can never claim to be a friend of the gay community as long as she continues to support immigration policies that bring Islamic extremists to our country who suppress women, gays and anyone who doesn’t share their views”. For queer Muslims, their identities become weapons against their communities.

Queer Muslims struggle with Islamophobia within the LGBTQ+ community as well. Within largely white queer spaces, anthropologist Niels Teunis argues,many queer Muslims feel trapped within the “Muslim Closet”:, too afraid to tell people about their Muslim identity because of its associations homophobic cultural values.

Authenticity

One of the primary conflicts queer Muslims face is feeling as though they are forced to adopt gender and sexuality labels that only exist in a Western context, such as “lesbian” or “gay”. This may prevent them from constructing an identity that feels authentic and aligns with their cultural background. After all, most identities within the LGBTQ+ community wereconceived in the West under the influence of postmodernism and queer theory.

Commenting on this Western construction of identities, Madjid Bencheikh argues “homosexuality is universal, what is not, are the forms it takes.” Homosexuality was indeed openly practiced in many Muslim societies from the seventh to the twentieth century.

Activist and scholar Houria Bouteldja highlights that, “in the Maghreb, homoeroticism has long been tolerated until colonisation imposed the norms of the rigid binary of homo/hetero.” This binary has made many queer Muslims feel threatened by members of the LGBTQ+ community, a phenomenon which Ludovich-Mohamed Zahed, an openly-gay Imam, terms as sexual imperialism” attacking people they deem to be queer where it is not claimed by them as an identity. In one study on queer South Asian women a participant quipped“white queers all emphasise coming out so much…next time a white person tells me to come out to my parents I’m going to tell them to make sure ‘cause of death: coming out because a white person told her to” is included in my obituary.”

Power in Resistance?

Being a queer Muslim is inherently complex as they have to overcome both homophobia and Islamophobia in order to be their authentic selves. However, sociology professor Momin Raman argues that “the ‘impossibility’ of gay Muslims is exactly their power in resistance. The disruption of their identity comes in challenging the ontological coherence of these dominant identity narratives which exclude gay Muslims as being impossible.” Whilst I sympathise with sentiment of Raman’s message and I understand the liberation that one can feel by challenging social norms I personally never felt this power when I was coming to terms with my identity.

I always felt weak. I always felt afraid. I always felt alone.

I am grateful to see organisations such as Sydney Queer Muslims and Al-Fitrah passionately supporting and advocating for Muslims of diverse sexualities and genders. I would have loved to have seen these organisations around when I was struggling with my sexuality and religious identity.

I hope to see a day when my worlds are no longer clashing.

A day when they finally align.