The way in which the non-disabled treat their peers with disabilities can be described as contortionistic. I know that I myself become super self-conscious in my attempts to not come across as an insensitive asshole. But at the end of the day, “acting is acting,” as Chained for Life’s Mabel would say. Chained for Life, in its tactful but banterous way, asks if we might be better off were we honest with ourselves about the ways that we interact with each other.

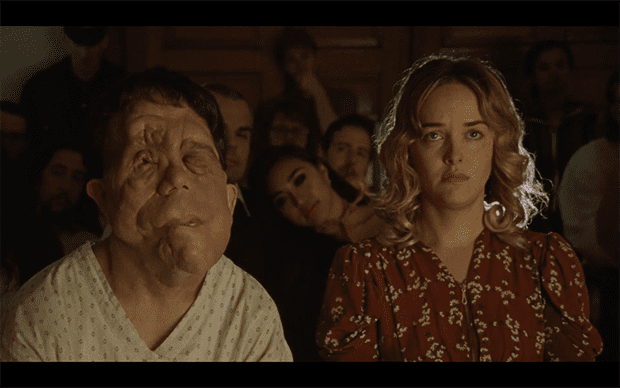

Writer and director Aaron Schimberg’s Chained for Life is about the (fictitious) shooting of a fictitious medical thriller. Character Herr Director (Charlie Korsmo) made the choice to cast people with actual disabilities in the roles of hospital patients. One of these characters is Rosenthal, played by Adam Pearson, who himself has a facial deformity called neurofibromatosis . However, Herr Director has still made sure to cast conventionally attractive thespians Mabel (Jess Weixler) and Max (Stephen Plunkett) in the lead roles of the blind girl and the German doctor, respectively. Chained for Life focuses on the way in which the cocoons of Mabel and Max unravel in the presence of those with disabilities.

I will get straight to it: as a piece of entertainment, the film is nothing special. The disjointed editing pretty much negates any chance of a holistic cinematic experience. As a film about the production of a film, Chained for Life cuts between footage with little desire to clearly telegraph what is ‘real’ and what is not. There is a vague sense that the production is moving forward, although just how is never made clear. This has the effect of reducing the plot to nothing more than a dollhouse. Production minutiae (disputes of hotel accommodation for the cast, interrupted shooting) provide room for the able-bodied characters to fumble and flounder in their interactions with their differently-abled peers. Chained for Life feels like a bunch of vignettes more than anything, and while this is very good for engaging the film on a more cerebral level, anyone expecting something escapist will be disappointed.

But if you are interested in a gentle roasting (either as the roastee or the roaster), then the film does an excellent job of reflecting the contortions of the non-disabled around people with disabilities. You see how bizarre it is to deliver compliments to someone like Rosenthal while staring at the ground. You understand the discomfort of someone sounding scared when they assess another’s disability/impairment or intellectualise their existence. The film, like a very honest and sentient mirror, asks you who you think you’re fooling.

Do not get the idea that this is a bitter and sardonic film. I don’t think I have seen a film as unpretentious and light-hearted as Chained for Life. This is largely the result of the masterful acting: Weixler and Plunkett, for instance, produce characters that are not so much hateable as they are understandably and even lovably misguided. Weixler does a fantastic job of rendering, underneath Mabel’s pained self-consciousness, a strong woman who wants to make her way in the world doing what she knows best. Max, while creepy, is at least worthy of a sort of bizarre pity, rather than outright hatred; this is a man who has so internalised the culture industry’s love for the eccentric genius that he wishes he had been born in the circus.

And then there is Adam Pearson. His performance is perhaps what gives the film its whole point. The patience and humility with which he lets his fellow cast members’ misguided, tone-deaf niceties slide off his back into the audience’s lap, ready for their examination. The sincerity with which Pearson presents himself on screen is a strong case against the logical extremes of method acting: why cast Daniel Day Lewis as a person who is crippled or Orson Welles as a black man when you can get the real thing? Is this fetish another instance of our contorted logic, or is it an awful compromise between star power and talent? If it is the latter, then do we really care for true experiential realism in cinema (which is what honest casting might provide), or do we just want to see beautiful people doing things?

In all, Chained for Life appears to be nothing more than a very convincing argument for cinematic representation for people with disabilities, wrapped in a sugary coating of light-hearted roasting. But I think that this is where the strength of the film lies: it does not want to dazzle or dramatise, because to do so might be to cheapen, or take away from something ultimately very serious. It just wants to humble you, not only for the good of your peers but also for yourself and the way in which you experience the world. For that, I think it is a worthwhile watch for anyone – contortionist or non-contortionist alike.

The Fantastic Film Festival runs from 20 February until 4 March in New South Wales and Victoria. For more information – https://www.fantasticfilmfestival.com.au/