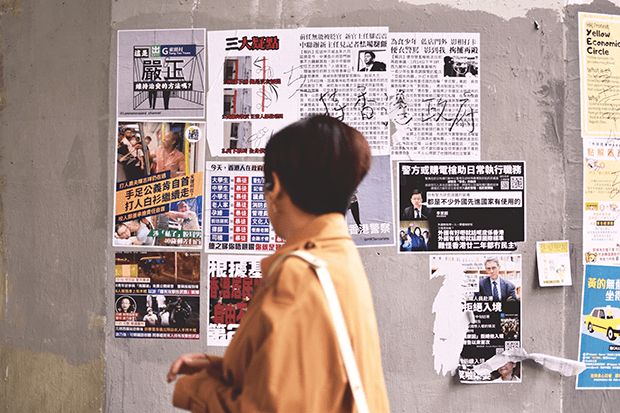

By the time I arrived in Hong Kong in late January, the pro-democracy movement

that had begun in June 2019 was tapering off. After half a year of sustained anger and violence, even those who held the cause closest to their hearts were feeling the

fatigue. The city bore aging scars of conflict: graffiti, out-of-order ticket machines,

and a quieter “million scream” (a nightly event where people yelled protest slogans

out of their windows). Lennon Walls—murals that collated pro-democracy Post-It

notes and posters—were becoming sparse as pro-police crusaders tore them down

with no one to put them back up.

Anti-government energy was far from fading. As an alternative to demonstrations,

pro-democracy (“yellow”) Hongkongers participated in the “Yellow Economic

Circle.” This scheme encouraged yellow consumers to boycott pro-police (“blue”)

businesses and financially reward yellow ones for their politics. Shops would decorate their interiors with pro-democracy symbols and slogans to advertise their political leanings to attract yellow customers.

Pottinger Lane in Central is famed for its quaint upwards-twisting cobblestones; here, it is decked out in splendid red décor for New Year. I took this photograph on the Tuesday evening before New Year—the next morning, the Chinese government would finally admit after a month of denial that the novel coronavirus was transmissible between humans. With the seventeen-year-old spectre of SARS looming over the city and faith in the government at an all-time low, all of Hong Kong would start wearing face masks.

On the third day of New Year, my relatives and I went to Tai Mei Tuk and the adjoining Plover Cove Reservoir, an outdoor recreational area in Hong Kong. At the peak of the SARS outbreak in 2003, the government had encouraged residents to escape our tiny flats and venture outdoors to breathe in some fresh, germ-free air. Many of us had the same idea during this outbreak.

Lion dances are a popular New Year spectacle; the Southern style performed by Hong Kong’s lions is—in my biased opinion—particularly agile and beautiful. These lions tend to visit businesses and houses to “eat” lettuce for good luck and receive red

packets. This year, I witnessed something rare: the qilin (麒麟, a mythical beast with

a dragon’s head and deer-like body) dance. This type of dance is traditionally

performed by Hakka ethnic minority communities.

Fai chun (揮春) are calligraphic decorations displayed on doorways during New

Year. Most of them nowadays are mass-produced but when visiting the small fishing

village of Tai O, we saw fai chun everywhere written in a beautiful, distinct hand.

Upon further inquiry, we discovered that these were handwritten by a local sifu.

Staying jubilant amid the paranoia, my aunts tried out the see-saw in an empty

playground. I had a go on the swing; it wasn’t not designed for adult legs. As a kid

growing up in Hong Kong, the swing had always been my favourite play equipment—but because of coronavirus fears, the one in our estate had blocked off

access until further notice.

Final day in Hong Kong. After a hike along the Insta-friendly Dragon’s Back trail, we

ended up in this market in Shau Kei Wan. Wet markets in Asia have gained a bad

reputation since the outbreak but they are a staple of everyday life here—and

increasingly regulated in light of past outbreaks of avian flu and African Swine Fever.