Redfern erupted like a wildfire that Sunday. It was 5 October 2014, and the annual heatwave was in full swing. Everyone had been sweating over their TV screens for hours. The Tudor Hotel on the corner of Redfern and Pitt was packed to the rafters, old timers and blow-ins all jostling for beer in their green and red jerseys. Just like when Whitlam was sacked or Cathy Freeman won gold, any Redfern resident can tell you exactly where they were when the South Sydney Rabbitohs took out the Grand Final, 30-6 against the Bulldogs, their first NRL premiership in 44 years.

I, for one, was sitting in the lounge room of my family’s George Street terrace. I don’t think I’d watched a football game in my life. Nor had my sports illiterate parents. But when Greg Inglis scored that final try, we were on our feet shouting like die-hard fans. There was an audible roar from the street and we raced out our front door, just as Sam the local hairdresser and his wife Nadia did; just as Lisa, who was my age, 15, and her mother Chuntao did; just as Uncle Max Eulo rounded the corner in his cowboy hat, wide smile, twinkly eyes; and crazy Jennipher ran up the street brandishing a red and green flag as big as she was. The chant rose up: “Glory, glory to South Sydney / South Sydney marches on.” After years of being underestimated and pushed around, the suburb of the underdog was finally on top.

I grew up in Redfern, two blocks from the station, a block and a half from Reconciliation Park. But the Redfern I grew up in is changing by the day, and the State Government’s proposal to demolish and develop the housing commission at the end of my street will change it beyond recognition. The government plans to knock down 2,012 dwellings for people on low incomes and replace them with 6,800 apartments, in towers up to 40 storeys high.

“The plans are shockingly dense,” says Sydney Lord Mayor Clover Moore. “They will triple the current density in the area to something more akin to development in Hong Kong or New York. It’s a scale and size that’s completely out of character for Waterloo and surrounding Redfern.”

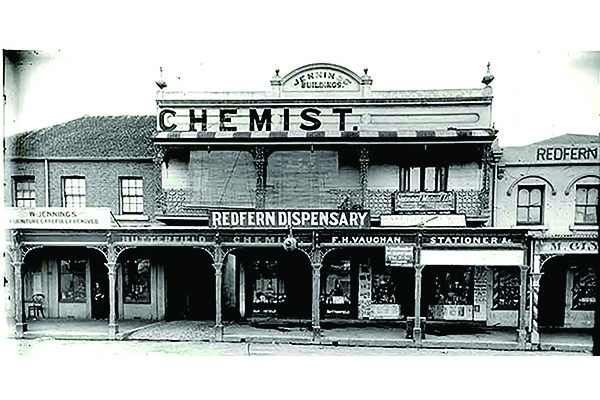

This won’t be the first big change to have swept through Redfern. People who live here can pinpoint the date they moved in by changes in the neighbourhood. There are people who moved in when the Surry Hills shopping village was still the Redfern Mall. There are the people who arrived before the Redfern Hotel became the Byron Map Gallery. There are people who remember when the Post Office was still a post office and you could buy heroin on The Block. My family history in Redfern precedes all that.

My great uncle Pietro arrived in Redfern in 1909. He came from a tiny town in northern Italy, called Toppo, and set up shop in Regent Street, already a slum, soon to be known as Sydney’s badlands. He created the mosaics for the Chapel of Irish Saints in St Mary’s Cathedral, carting his heavy tiles and tools from Redfern into the city every day in a wheelbarrow. One mosaic and 200 pounds later, he brought the rest of the family out from Italy, including my great grandfather.

In the early 1990s, my mum first moved to Redfern. She was sharing a house with a violinist on Wells Street, between a funeral parlour and a laundromat (now a gin bar). “The only bars then were on the doors and windows,” says Mum. “Kids from the housing commission would stick their hands through and grab anything in reach: jewellery, chocolates, small change”. The main drag was filled with local shops, representing the melting pot of multiculturalism that was Redfern at the time. There was the Portuguese butcher, the Vietnamese bakery and the Lebanese family grocer, known for their good conversation and fly-covered fruit.

When I was two, my parents moved from their Potts Point rental apartment into our terracotta terrace on George Street. Just like the neighbours to our left and our right, we’d bought in Redfern because it was the only suburb a young family like ours could afford. “We couldn’t afford Newtown or Darlinghurst or Surry Hills, but people were still scared of Redfern,” Mum explains.

The hustle and bustle and sense of community on Redfern Street extended around the corner and we Redfern kids stuck together. Samia Piper-Larkings lived a few minutes away on Regent Street. Her dad was an architect, and helped out Mick Mundine at the Aboriginal Housing Company. We met in Ms Yanakouros’ kindergarten class in Ultimo and walked to school together almost every day. We strolled down Cleveland Street, took a right at Regent and wandered past the Lord Gladstone Hotel, then a sleazy pub with sticky carpet floors, and a ragtag group of old men leftover from the night before. I spoke to Samia again just recently. “Remember at school,” she said, “people would be like, ‘oh… you live in Redfern’, but we didn’t think anything of it.” In high school, girls changed trains at Central to avoid Redfern and were too scared to catch public transport to our houses.

I don’t remember when I first met the Pedersens (the neighbours two doors to our right). They’re a family of long-haired, long-limbed, blonde athletic types. The eldest daughter Isabel was born 10 days after me and we were fast friends. We spent our Saturdays sitting outside our houses flogging goods to the neighbourhood. It usually involved baking. Our street distinctly lacked foot traffic but we didn’t let that get in the way of good salesmanship. Eventually we’d tire of sitting on the stoop, pool our earnings and head to the corner shop, which was run by a Palestinian guy called Ali, who arrived in Redfern not long after we did. Dad set him up with an immigration lawyer to help bring the rest of the family to Australia, back in the days when that was possible. One by one, sons and daughters, his wife and the occasional cousin started to pour in. Hazem, Ali’s eldest son, had a penchant for imported sweets, which was great for us kids, and an ambition to achieve Instagram fame. He now runs the Redfern_Convenience_Store Instagram page, which boasts 15,000 followers and a writeup in The Sydney Morning Herald. Redfern’s always been the place to go if you were looking for a break.

Redfern is Gadigal land. It’s been the location of corroborees and trading routes for thousands of years. When the gangs of convicts and settlers rendered the tank stream undrinkable, some Gadigal people retreated from the harbour and made Redfern their home. The Eveleigh Railway Workshops brought Indigenous people, seeking work, from across the country all through the 19th and 20th centuries. It offered job security and the prospect of a stable home to people who had been forced off their traditional country.

Redfern was at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It’s where Mum Shirl established the Aboriginal Medical Service, and where the Aboriginal Legal Service and the Aboriginal Housing Company were born. It’s home to Paul Keating’s Redfern Speech, where he declared: “It was we who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life.”

I meet Pam Jackson in the cafe beside Redfern Oval, halfway between the Rabbitohs’ training ground and the spot where Keating gave that iconic speech. Pam moved to Redfern in the early 1950s. She was 13 when her dad got a job at the railway. In the 1960s, she was one of the first people to live in the Matavai and Turanga Housing Commission towers at the bottom of my street. Curiously, the towers that provided social housing to members of the Indigenous community were named after spots where Captain Cook stopped on his voyage through the South Pacific.

At the time of construction, the towers were state of the art. The brochure that accompanied them said they embodied “the best and most modern thinking about the way… people should be housed to give them the most pleasure and enjoyment as well as safety and comfort in their surroundings.” Over time, conditions deteriorated and they gained a reputation as Sydney’s ‘Suicide Towers’, but despite the negative perceptions, the neighbourhood spirit prevailed.

“It’s just the community, always,” says Pam. “Walk down the street and know someone, walk into the shop and know someone. It’s just that. Always.”

In January 2019, the New South Wales Government announced its plan for the redevelopment of the Waterloo Tower Apartment Blocks, where Pam has lived for decades. The government aims to demolish the entire Waterloo community housing precinct and replace it with a “mixed urban village” up to 40 storeys high.

Sixty-five per cent of the new development will be privately owned, 30 per cent will be social housing and only 5 per cent will be considered affordable housing. Despite boasting increased social housing, the government is only providing 28 new social housing units.

“With a social housing wait list of over 50,000 in NSW, I believe this is a missed opportunity, and against the wishes of the community,” says Clover Moore.

Pam is the Aboriginal Liaison Officer for the Waterloo Tower Apartment Blocks. She brings the community’s concerns to the government with hopes of being heard. “It will trickle down, it will trickle down,” she says. The community feedback echoes Clover’s call for increased social housing.

The City of Sydney has proposed an alternative to the high-rise, high-density State Government plan. It would give the Matavai and Turanga towers a much needed refurbishment and develop the rest of the area with 4 to 13-storey apartment blocks. It would deliver 5,300 homes in total, of which 70 per cent would be social and affordable, and there would be dedicated affordable housing for the Aboriginal community.

“Bring it back to the days when social and affordable housing was easily available to Aboriginal people,” says Pam. “Their children are growing now and they’re having to move out to other suburbs. Redfern’s always been their heart and soul. That’s what I think and that’s what nearly all of [the tenants] have said.”

According to Homelessness Australia’s 2017 report, while Aboriginal people make up 3 per cent of the Australian population, they make up 23 per cent of people living in homelessness. Despite the demand, the government has included no reference to specific Aboriginal social housing within its plan. “This is, from my perspective… from how I can see it, but I think they’re still teetering around on eggshells,” says Pam.

From 1973 when the Aboriginal Housing Company bought its first six houses with a grant from the Whitlam Government, ‘The Block’ provided refuge and accommodation for the Aboriginal community. However, since 2004, when the bulldozers rolled in to level it for redevelopment, Aboriginal housing in Redfern-Waterloo has been scarce.

Lani Tuitavake first arrived at The Block as a kid. She used to venture out from her home in Botany to the Aboriginal Medical Service with her mum.

“My background is Tongan,” she explains. “My mum, in the ‘70s, she was an illegal immigrant and wouldn’t be comfortable going into a doctor’s surgery. She had an idea that the doctors would report her to immigration.”

Redfern, and its services, offered Lani and her mum security. “The Block, to me, is a safe haven,” she says. “Everyone knew everyone. Everyone knew your kids. It felt, for me, despite all the hype and what have you, that there was a sense of safety”.

Lani has lived in Redfern for about 28 years. She started doing some cleaning and minor administrative work at the Tony Mundine Gymnasium on The Block. Today she’s the chief operating officer at the Aboriginal Housing Company. “Redfern’s a place that, when your luck’s down, you cross paths with people. That’s my story,” she says.

Lani’s perspective on the Waterloo development reinforces the community sentiment. “What we want to see is more housing,” she insists. And more housing for the Aboriginal community and other diverse communities that have traditionally made Redfern home. “…It would be good to see more [of these people] being represented, not just in murals, in artwork, but in providing housing for people and employment.”

In early 2015, we moved out of Redfern. The property market was starting to boom and Redfern was Sydney’s hottest spot. We sold our house to a family from Avalon, whose Northern Beaches mansion had featured in Vogue Living. They wouldn’t have set foot in Redfern ten years prior. They’ve now rented it out for a small fortune to a young couple and are negative gearing my childhood home.

Since then my dad has refused to return to Redfern. It sends him into a depressive spiral. It takes an army to get him to cross Abercrombie Street. When you drive down our old street now, you pass a PR firm, two boutique gyms and three hipster coffee shops. Sometimes we take a peek at properties for sale in the neighbourhood with hopes of moving back. But Redfern now isn’t what it was back then. And if the State Government has its way, it certainly won’t be the same tomorrow.

I acknowledge the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation, the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Redfern stands, and recognise their continuing connection to land, water and community. I pay respect to Elders past, present and emerging.