Many people have never heard of locksport. It’s a niche hobby, some might say a strange one; we can even call it underground for its obscurity. Yet, people around the world are meeting up—in seminars, conferences, and competitions — to practice it.

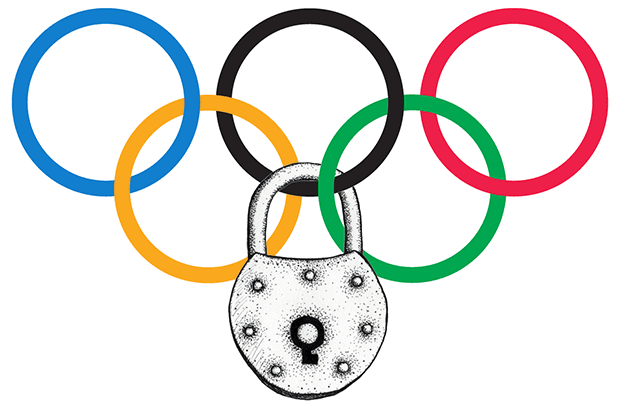

Simply put, locksport is recreational lock picking. It is the hobby of opening locks without keys for fun. It is a bit like solving jigsaw puzzles. Each lock, like each set of puzzles, has a different personality that poses a unique challenge. Locksporters need to first understand how each lock works. Then, with their hands and tools, they try to conquer their locks of choice. Some purchase lock picks on the internet or in retail stores; some make their own. Most of the time, they pick their own locks and they do it for enjoyment. It has nothing to do with thievery or breaking in. Although locksport is a global phenomenon, I will focus on the Australian scene here.

Nowadays, lock picking enthusiasts call their hobby locksport — opening locks without keys for fun. Although we can find many historical examples of recreational lock picking, the exact origin of modern locksports is contestable. The term “locksport” was probably first used by a community with the forming of Locksport International in 2005. The word “locksport” itself, though, might have been coined years ago. The purpose of the term was to distinguish hobbyists from thieves and other unethical lock pickers. The modern hobby of organised recreational lock picking dates back to the late 1980s and early 1990s. David De-Val’s book, Lock Picking, was published in 1987. In 1991, a Roof and Tunnel Hacking group based in Massachusetts also published a pamphlet, The MIT Guide to Lock Picking. It was one of the first widely available lock picking instructions. The rise of recreational lock pickers also coincided with the rise of the internet. With Facebook groups, YouTube channels, blogs, and websites, locksporters grouped their own communities and shared knowledge. TOOOL (The Open Organisation of Lockpickers), one of the first international locksports communities, was first formed in 1999 in The Netherlands. Now, TOOOL communities around the world hold monthly meetings. Notably, there are over 1000 official TOOOL members in Berlin. They gather for seminars, general meetings, and competitions. In Australia, the TOOOL community meets up in Melbourne. Lock and security enthusiasts also hold regular conferences around the world.

Last year, the OzSecCon, a “conference dedicated to locksport and physical security”, was held from 14th to 16th of June in Melbourne. The conference included talks, professional training, workshops, and competitions. I talked to Topaz Aral, an organiser of the event. Topaz is a computer security and penetration testing professional. He said although many lock picking enthusiasts are IT professionals, locksporters often come from diverse and surprising backgrounds. “We have one person coming in presenting at the conference who I believe is a mechanic or a tow truck driver,” Topaz said. “He’s done some amazing research.”

Topaz was 13 when he picked his first lock. “It’s kind of like a puzzle,” he said. Usually, beginners learn to use lock picking tool sets first. “It requires a little bit of practice, a little bit of time, to get competent at it.” Most people think Topaz’s hobby is cool when they first learn about locksport. Others get “surprised it’s a thing” and question its legality. “I’m not a lawyer but the legal advice tends to suggest that it is perfectly legal to have this as a hobby,” Topaz said.

The TOOOL website has outlined the laws of many countries and states in relation to lock picking. Its legality, therefore, depends on where you are in the world. In general, as long as locksporters are picking their own locks and not using their skills to commit theft, trespass, or other criminal acts—it is likely to be legal. Morally speaking, I would compare lock picking to martial arts. Hobbyists can choose to use their skills to challenge their mind and body, or they can be used for dubious means. As most skills could be adapted for questionable deeds, I think lock picking itself is not a concern. Instead, we should worry more about the moral quality of those involved. The TOOOL website points out if something from the locksports community is likely to endanger public safety, such as the development of a new, dangerous technique; then, ethical and possibly legal actions should be taken. Locksporters, in general, use their skill only in recreational ways—they are decent humans from diverse backgrounds who have discovered a love for lock picking in different ways.

Alex Holmes, a member of the Facebook group, Australian Locksport Guild, shared his experience with me. Alex, a private investigator, could already pick a lock when he was in junior high school. His interest in locksport originates from seeing it in a movie or a video game during childhood. He emphasises that private investigation work “should never need lock picks.” Mr. Holmes’ skills would enable him to “identify levels of security” and “enter vehicles and other obstacles within a few minutes.” His favourite type of lock picking is single-pin picking, preferring quieter methods over noisy tools like bump keys and snap guns.

Another Facebook group member, IT professional Sean Rodden, first discovered locksport through the YouTube channel LockPickingLawyer, which has over 60 000 subscribers. He enjoys picking locks because it enables him to use his hands and it provides an outlet for creativity. He finds crafting his own lock picks very rewarding. The “craft side” of locksports offers a relaxation away from the routine of his office day job. It is more convenient than other workshop hobbies such as carpentry because the required tools are portable. He added that he never picked locks outside of the hobby. For apartment residents like Sean, locksport is ideal because it doesn’t take up space; practicing it requires only a lock and a lock pick.

No one can give an exact reason for why, throughout history, some of us are so fascinated by lock picking. In a way, our desire to open locks without keys is a metaphor for humanity’s longing for freedom. Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote at the beginning of The Social Contract: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” Perhaps due to the constraints imposed on us by our world, we yearn to loosen our shackles. In proving that no locks could restrain us, lock picking acts as a cry of freedom—it becomes an act of defiance. In another way, locks can also symbolise security. Through always challenging the concept of impregnable security, we find that nothing can really be kept safe. Paraphrasing Shakespeare, lock picking shows us the world is an oyster: there’s always a way to crack it open.

While the illusion of perfect security is dead, recreational lock picking is becoming more popular. Locksporters must use their intellect, their hands, their skills to meet every challenge each lock poses. I think part of being human is to be playful, to solve puzzles, and to create challenges. So, as long as we are human, some of us are bound to pick locks. Not necessarily because it means anything, but only because it makes us feel alive. Lock picking is — like many things we do — a source of pleasure and a way to fulfil our human potential.