Decades of middle class pearl-clutching would have you believe that heavy metal and feminism are more foe than friend. In reality, they’re entirely compatible — and share a common enemy in, amongst other things, the Church. Their relationship is especially visible in the 1990s, the decade that brought Third Wave Feminism and a new generation of metal artists.

Bracketed by two historical instances of high profile sexual misconduct — the Anita Hill Trial in 1991, and the Clinton-Lewinsky “sex scandal” of 1998, the 1990s were a pivotal moment for feminism. But this extended far beyond the world of American electoral politics.

More women were engaging with heavy metal than ever before. Arch Enemy, Lacuna Coil and Nightwish lead a charge of female-fronted acts that continue to influence the genre today. In the punk scene, Riot Grrls aggressively fought their way to the front of shows, onto line-ups and into history. Women were angry, growing into adulthood through the Reagan era and into an age where things seemed to be getting better but in reality very much weren’t.

Religious violence was by no means a new concern for metal. Reviled by the Church, metal’s flirtations with Satanism and criticisms of organised religion are as fundamental to the history of the genre as Tony Iommi’s sliced off fingertips. Feminists too have toyed with reclamations and perversions of christian history and scripture, from the mythology of Mary Magdalene to the Salem Witch Trials.

Sacrilege and seduction are familiar bedfellows. As the Church exerts its considerable power in controlling our social, sexual, and reproductive freedoms, who can blame us for taking pleasure in blasphemy and desecration?

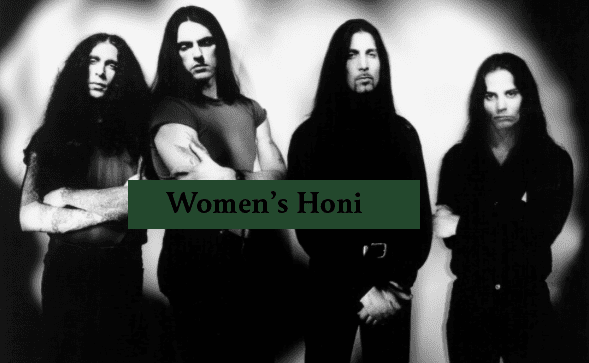

Though there are certainly metal bands more sacrilegious than Type O Negative, there are none more seductive. It would be incorrect to reduce their back catalogue and legacy to the indisputable fact of their mass sex appeal, but it remains a large part of their allure.

Type O Negative are Mills & Boon for metalheads, Peter Steele the leading man of their gothic romance novel. Tall, menacing and supernaturally handsome, the late frontman commanded the hearts (and loins) of Type O’s enormous female fan base. The band were aware of this, and marketed accordingly: Steele had his teeth filed to points, posed naked for Playgirl, and appeared as a special guest on a Jerry Springer episode about groupies.

Though Steele’s vampiric good looks are fundamental to the mythology of Type O Negative, his lyrical treatment of women is far more interesting.

The dominant sound of 1980s metal was Thrash. The Big Four — Anthrax, Slayer, Metallica and Megadeth, emerged in the mid 80s in direct opposition to Reagan era politics. Metal in this period was still the male-dominated space that it had been since the early ‘70s. Though metal is inherently political and frequently left-wing, it is by no means immune to the plague of the patriarchy. Lyrical depictions of sex and sexuality ranged from garden variety misogyny and objectification to violent depictions of rape and sexual violence.

Which is to say that though women had been engaging with Metal as fans and musicians since its origins, it hadn’t welcomed them with open arms.

It’s important to note that Type O Negative is not a feminist band. I would go so far as to say that Type O Negative is an anti-feminist band. Despite this, they continue to garner the affections and loyalty of an enormous female fan base, this writer included. Why?

Though they can’t be called feminist, Type O appear to cater to the female gaze. 1993’s Bloody Kisses and 1996’s October Rust, the most well known and critically favoured of their back catalogue, are laced with themes of devotion and adoration. Much of their work elevates women as sexual beings to holy, almost biblical figures. For women whose sexual, social, and reproductive freedoms were still limited by the influence of the Catholic Church, such imaginings of their sexuality were incredibly enticing. Besides, Goth was experiencing a cultural renaissance, and Type O Negative were the Goth Metal band.

Type O can also be considered in contrast to the work of their peers. Cannibal Corpse’s 1992 release “I Cum Blood” vividly illustrates an act of Necrophilia. Though Type O’s first album, and the trajectory of Steele’s own career, carried similarly violent themes, they are mostly remembered for their work after Slow, Deep and Hard, their first and most overtly misogynistic release.

“Forgive her…for she knows not what she does” are the words breathily uttered by Steele as the introduction to ‘Christian Woman.’ Archetypically Type O, the song is one of the band’s greatest hits. Like everything written by Peter Steele, it’s incredibly horny. Its influences can be traced to the Danzig songs ‘Mother’ and ‘She Rides’, both about sex and Satan and women experiencing sexuality despite Christian morals. Glenn Danzig’s compelling stare and muscled physique paved the way for the aesthetic success of Peter Steele, and both men toed an uneasy line between object and objectifier, sex symbols as much as they were musicians.

In an album laden with camp eroticism, ‘Christian Woman’ is not remarkable for its r-rated content, but for how it reflects a particular intersection of third-wave sexual politics and ‘90s pop culture. The Goth renaissance of the 1990s infected all aspects of media, from music to film. Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the highly erotic Francis Ford Coppola release of 1992, is as much a product of the 1990s concern with female sexuality as ‘Christian Woman’. Though its material power was ever-present, the cultural shadow of the Church seemed to be waning. Vampires were very much in vogue, and the sex positivity that would later be fully realised in shows such as Sex and The City was on the rise. What better time to explore women’s sexual expression and repression, and what better medium than Goth?

Bloody Kisses is Type O Negative’s first album to achieve critical acclaim, but October Rust was its breakthrough. By the point that October Rust had been released, Steele had achieved a potent ménage à trois of 90s pop culture: an appearance on Jerry Springer, a centrefold in Playgirl, and the endorsement of Beavis and Butthead. In October Rust, the band’s lasting legacy as the sensual lords of Gothic Metal had been realised.

October Rust is the album that defined Peter Steele as the ‘Ultimate Fantasy Goth Boyfriend.’ “Be My Druidess”, the 4th track off the album, is as unabashedly carnal as the greatest of Mills & Boon romance. “I’ll do anything to make you come” intones Steele, in between verses that are little more than romance fantasy sex scenes. This is where Steele’s use of a perversion of the female gaze comes into play — he seemed acutely aware of the fantasies of his female fans and was more than willing to accommodate them.

In the same sense that he was literate in the stylings of Mills & Boon, Steele was unafraid of offense and taboo. He relished in it. The particular taboo that Steele explored in October Rust? Menstruation, which he referred to as “unholy water” and a “sanguine addiction”.

‘Wolf Moon’, the song from which these lyrics are taken, encapsulates the ultimate appeal of Type O. It contains the tenderness of ‘Love you to Death’ and the eroticism of ‘Be My Druidess’ in a seven minute ode to period cunnilingus. It also explains the band’s long-standing allure: period shame is an issue that afflicts women to this day. It’s no wonder that women are drawn to this heavy metal Fabio.

However, understanding the appeal of Type O Negative, specifically the way that they appeal to women, does not absolve them of the misogyny that plagues their peers. Type O Negative are as misogynistic as Cannibal Corpse. From their first album, which was born of Steele’s desire to kill his girlfriend and then himself, to their name, which is based on the fact that the type O-blood type is untraceable in semen tested as a part of a rape kit, Type O are mired in the same structures of patriarchy that dominate all heavy metal.

I would be surprised to see an academic attempt at conceiving of Type O as feminist or feminist-adjacent, though metal journalism and culture writing on the band often skates on such thin ice. Really, Type O as an individual band is not important: though their influence and relevance can not be overstated, they’re an example of the way that media can co-opt feminist messaging for its own gain. Which is not to say that Type-O did such a thing consciously — for all of their many political flaws, they were honest about being “four dicks from Brooklyn”, a band as firmly rooted in its working class origins as it was in goth and doom metal.

Type O Negative, and others like them, are merely products of the third-wave liberal feminism that arose in the 1990s, that has been used from Type O to Twilight to obscure the thrum of misogyny that underscores all media. This doesn’t mean that such things can’t be enjoyed, but that as feminists we should be constantly critical of the media that we consume.

Their feminist ideology may leave much to be desired, but their function as a guilty pleasure? Very satisfying, indeed.