Scattered across Sydney’s network of railways and light rail are remnants of former railway stations. Three of these — Woollahra, Enfield South and Ropes Creek — tell their own individual stories about the characters and histories of each suburb and the vicissitudes of local politics.

Woollahra Station

Disembark from Edgecliff Station and turn right on the posh and reserved Ocean Street where curious Tudor windows dress red brick flats, This opens up to a tree-lined residential enclave. Once you’ve passed the quaintness of the Polish and Russian Consulates on Trelawney street, head onto Edgecliff road. Be prepared to be greeted with an unassuming bench with stunning views of a railway line. It is here that holds the only remnants of the abandoned Woollahra station project.

The unassuming nature of Woollahra Station is partly due to affluence. A 2-bedroom house in Woollahra typically commands around $2.25 million. Indeed, the view that this bench affords arguably stretches all the way to the exclusive manse on 77 Wallaroy road that the University owns.

The story of why and how Woollahra Station was abandoned is both intricately connected to Woollahra’s wealth and a state government that struggled during the 1960s. Archives from the Sydney Morning Herald suggests that the proposal of Woollahra Station – and by extension, a plethora of others constituting the Eastern Suburbs line – was made during the Heffron premiership between 1959–1964. Evidence from the Herald’s Archives in 1963 indicates that the Eastern Suburbs

line was delayed and the government had projected that the line would cost 29 million pounds . This was to be one amongst other delays in the chequered history of Woollahra Station and much of the Eastern Suburbs railway project.

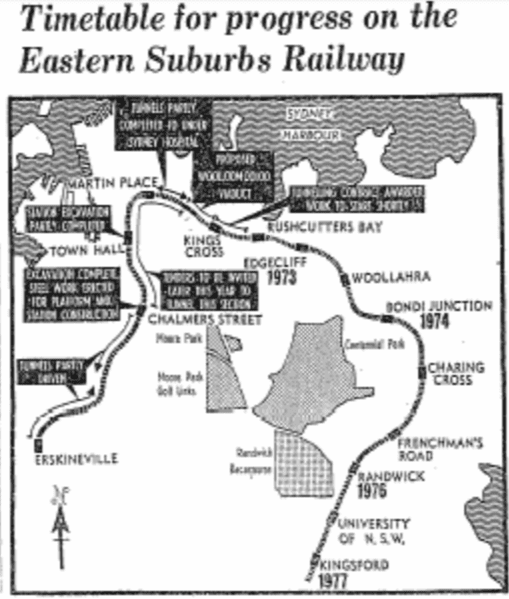

This diagram depicts the Askin Government’s vision for the Eastern Suburbs line in 1968. Had Askin and Morris succeeded in persuading the residents of Woollahra, it would be likely that Sydneysiders would have been able to alight at present day King’s Cross and connect to landmarks such as Rushcutters Bay and UNSW. Indeed, one can argue that a station for Randwick in proximity to UNSW came nearly 45 years late in the form of the newly opened light rail by the Berijiklian government.

However, the latter half of Askin’s Eastern Suburbs line caused several instances of delays owing to fierce local resistance from the suburbs affected – a notable one being Woollahra. This sentiment is perhaps best summed up by a combative response from the then Transport Minister Milton Morris to Woollahra in August 1973 as reported by the Herald: “No matter what the residents on the picturesque higher levels feel about it, hundreds of families near the site want that station for convenient rapid transport, and they’ll get it.”

Finally, besieged by local rancour and the election of Neville Wran as the NSW Premier, the Eastern Suburbs line was revised. The Wran government’s revision thus excluded Woollahra Station alongside the vast majority of the southern portion of 1968’s proposal — from Rushcutters Bay to Charing Cross, Frenchman’s Road, Randwick, and UNSW — with Kingsford existing as Kingsford Smith.

Enfield South Station (Enfield Intermodal Lookout and Intermodal Logistics Centre)

Amongst Sydney’s collection of lost stations, Enfield South stands as one of the city’s most obscure platforms. Located just off the intersection between Punchbowl and Cosgrove Road, Enfield South has all but vanished, leaving behind key remnants of its past as a railway workers’ train.

Intimately connected to the nearby Enfield Tarpaulin Factory and Flemington-Campsie Goods Line, Enfield South never served as a railway line for the public. Rather, according to the NSW Rail and the Railway Digest (2008), it served as a railway platform for workers at the Enfield Tarpaulin Factory until 1996, connecting Campsie to Lidcombe Goods Junction- with similarly purposed platforms such as Enfield Loco, Hope Street, and Delec decommissioned in the same year.

All these facilities were put forward in 1914 by John Harper, the then Chief Commissioner of NSW Rails to enhance Sydney’s industrial prominence amidst a dramatic increase in rural productivity in NSW at the time. The chief purpose of Enfield South was to service railway workers who worked at the Tarpaulin Factory. This was a facility that specialised in manufacturing tarpaulin — a highly durable, water-resistant or waterproof cloth that drapes over containers in order to protect their contents.

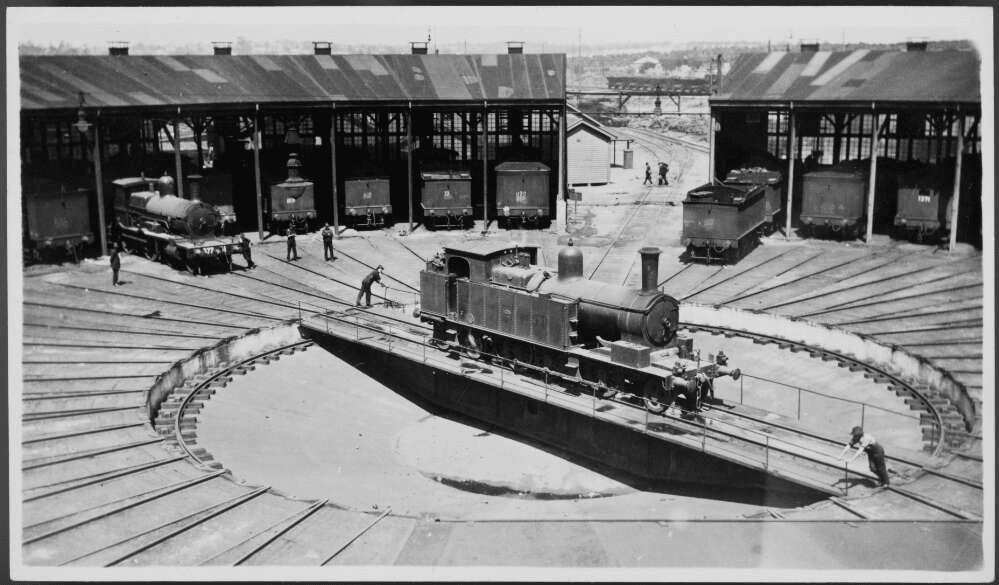

Despite its closure, the Enfield South site is today home to several significant architectural artefacts considered to constitute “state significance” by heritage experts in a 2009 report to NSW Ports advocating the conversion of the derelict Enfield site into a public historical nature reserve. One of these is the Enfield Intermodal Lookout, opened in 2017 by NSW Ports, providing a wooden walkway, ecological reserve and a lookout. The walkway bifurcates the austere cast iron of the derelict Tarpaulin Factory and the vast Enfield Marshalling Yard. The latter comprising an impressive complex boasting artefacts such as two large locomotive turntables to facilitate the turning of steam locomotives as without them these trains would clock substantially lower speed in their return journeys.

Other notable structures still standing on the Enfield South Station and Marshalling Yard includes the Yard Master’s Office, Administration Building, and Pillar Water Tank. The Yard Master’s Office, as its name implies, once hosted the Marshalling Yard’s Master and were responsible for tracking wagons alongside ensuring that they are properly sealed prior to departure. On the other hand, the Administration Building served routine administrative purposes and have since been subject to deterioration and graffiti. Of these structures, NSW Ports expects to retain the Pillar Water Tank and Tarpaulin Factory citing the low significance and derelict conditions of other buildings.

Contrary to concerns that the absence of steam locomotives and opening of the Intermodal Lookout suggests that the future of the Enfield South, Loco, & Marshalling Yard is in decline, its contemporary incarnation as the Enfield ILC (Intermodal Logistics Centre) means that the complex maintains its role as a key artery in Sydney’s logistics network. At status quo, the Enfield ILC is NSW’s largest railway-based intermodal logistic centre. Furthermore, the NSW Government, since at least 2018, has given NSW Ports the permission to expand the Enfield ILC to form which is estimated to cost about $190 million by SBA Architects – the firm that won the Enfield ILC design competition.

Thus, although traces of Enfield South Station have amalgamated into the lives of the busy Sydney Metropolitan Freight Network and Logistics Centre, its future looks bright and will maintain considerable significance to the community in Strathfield, Enfield, and Belmore for years to come.

Ropes Creek Station

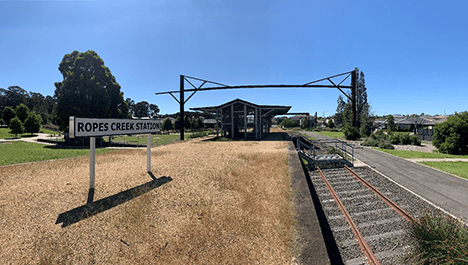

Alighting at St. Mary’s Station along the Western line, strolling north for nearly an hour past quaint streets and the tree-lined Ropes Crossing precinct, I arrived at the former Ropes Creek Railway Station. Cleverly camouflaged amidst a quiet residential quarter, the former railway station now doubling as a local recreational park and historical artifact. A small stair connects the street to the platform, with a signpost clearly labelled: “Ropes Creek Station” seemingly inviting contemporary passengers to contemplate trains terminating on either side of the tracks.

Unlike most of Sydney’s other disused stations, Ropes Creek’s platform is remarkably well preserved with remnants of railway tracks still visible today around the platform. Albeit the headhouse has clearly been restored since closure to remove seats. Instead an I-beam and related machinery are displayed behind fenced enclosures now replacing the interior.

At first glance, one might wonder why the line perished. After all, the modern day St Mary’s precinct is a firmly residential area and a pedestrian journey from Ropes Creek to the station entailed a fifty minute ordeal. Ropes Creek was constructed during World War Two in 1942 under Curtin’s prime ministership, serving the Department of Defence in order to transport workers and service members who worked at the nearby St.Mary’s Munition Factory. The factory was built to supply ammunition and related weaponry for the Australian war effort. Following the outbreak of the Korean War, the site was once again utilised to manufacture munitions until the post-Cold War era saw a period of terminal decline for St Mary and by extension, Ropes Creek and its sister stations — Dunheved and Cochrane.

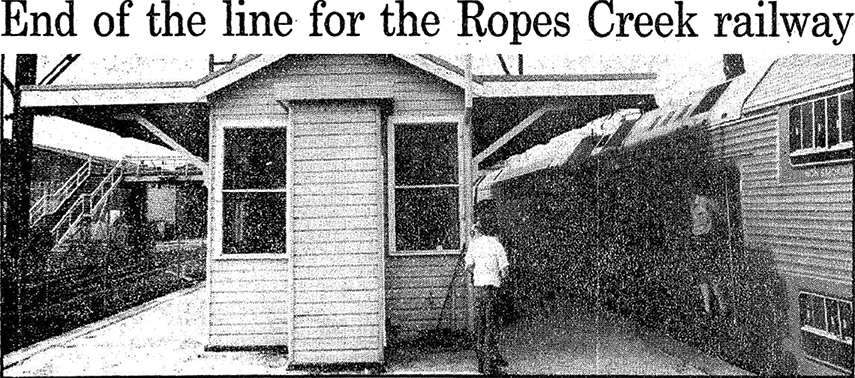

The last regular passenger trains to alight at Ropes Creek and its two sisters did so on March 21, 1986. The rationale – according to the Sydney Morning Herald – behind Ropes Creek’s demise was that the footfall to the station gradually dwindled due to the decline in service members serving St. Mary’s munitions factory alongside the closure of the factory itself. This, in turn, meant that after World War Two there was seldom demand for transport on the line. Indeed, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that the Federal Government spent approximately $250,000 to maintain the Ropes Creek line. This is a major loss given that fares collected from the line were a mere $5,000 per month, and thus significantly smaller than the government’s investment.There were only three scheduled trips a day on the line until its closure.

Thus, today Ropes Creek Station and her sisters stand as a living remnant of Sydney’s role in the Second World War. The station serves the local community at Ropes Crossing as a public space to rest and play, with children’s slides adorning its once sombre surroundings.