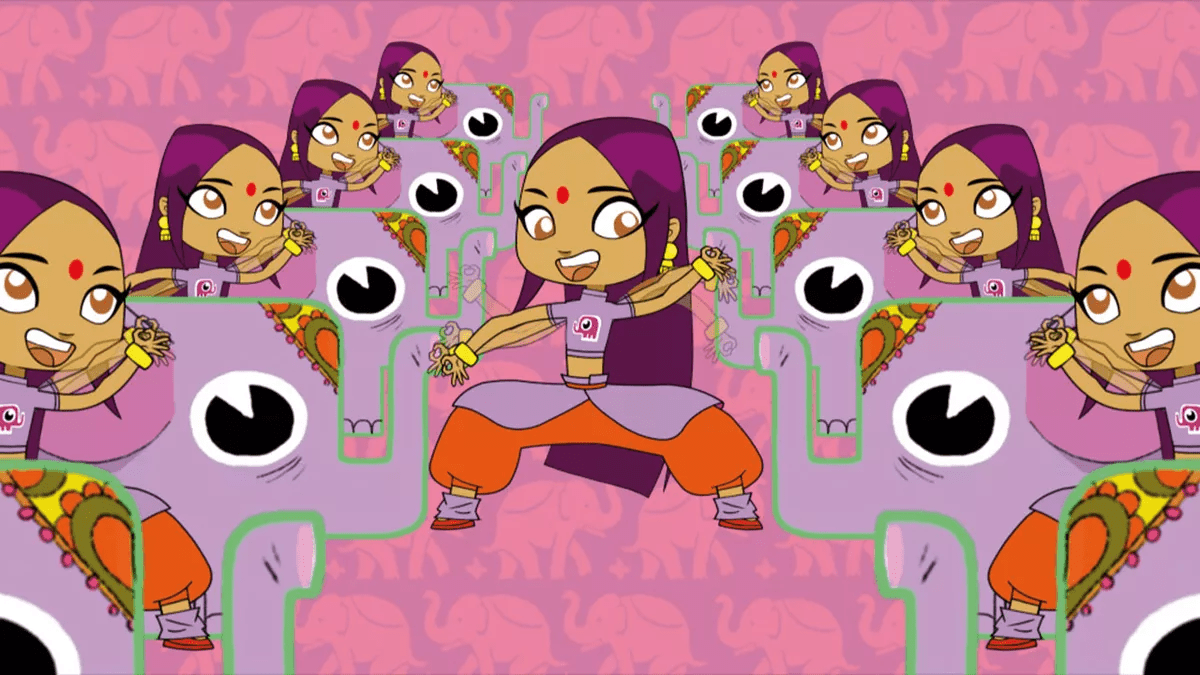

When I was ten years old, my father lived in Hong Kong. Whenever I visited him, a whole month every summer, I’d stay up all night watching TV. This was, of course, before I believed in words like ‘jetlag’ and ‘healthy sleep cycle.’ I stayed up late because Totally Spies would come on at 2am every night. But, one night, I slept through Totally Spies. I awoke to a pre-teen crime show, Sally Bollywood: Super Detective. It wasn’t until that moment that I realised my identity affected how I consumed popular culture. My first thought was: it’s so exciting to see a brown girl on television outside India. My second thought was: this is the stupidest thing I’ve ever seen. I had so many questions about the show. Why was her last name Bollywood? How did this twelve-year-old Indian girl have so much agency? Why couldn’t I, a ten-year-old Indian girl, relate to her character on levels more profound than the colour of our skin? Did my anglo heritage make me “inauthentic”?

Sally Bollywood’s description states that she lives in a city “where people of different nationalities and ethnic groups make up the population.” I found it peculiar that this was something they needed to specify, as if people of different nationalities and ethnic groups didn’t make up the population of almost every city. It almost sounded like the only reason such a character was allowed to exist and be the protagonist of a French-Australian television show was to showcase that other ethnicities existed and were allowed to have their stories told in an industry that was predominantly Anglo-Saxon. Such descriptions are not commonly found for other shows.

These feelings permeated other aspects of my life. From then on, every piece of western media I consumed was tainted. It was really easy to see how much I wasn’t being represented. Hannah Montana disappointed me, Wizards of Waverly Place disappointed me, Barbie disappointed me. It was odd that I was looking for validation in these places when I had an ocean of Indian content to choose from. I don’t know why Son Pari and Shararat didn’t matter to me; why they didn’t feel enough. But I think I am able to see more of the picture now. I thought these shows reflected real life; that American high schools had floor-to-ceiling length posters of their basketball team, that Miley Cyrus went to high school with a wig on, that it was possible to be a teenager and save the world. While one of those things might be true, the lack of brown representation in the media created all these spaces I wasn’t welcome.

When I wrote my first story, all of my characters were white. They had common white names, lived in New York – a city I wouldn’t visit for eight more years – and were royalty. It was a terrible story, the plot was in shambles, and the characters barely had a second dimension. It was a while before I realised I was writing about characters I assumed people would want to read about, rather than characters who were authentic, tangible, and present in my everyday life. I genuinely thought that every aspect – supporting roles included – had to be white and that there could only be one token character of colour. The internalised racism I harboured was so intense that the presence of more than one person of colour offended me. I felt indebted, uncomfortable even, with the space they took up.

As artists and people of colour, the capacity of art to challenge and progress society depends upon the lengths we go to be true to ourselves. Our work should reflect our values, not anglocentric methods of storytelling. I robbed myself of hundreds of tales born in my country in favour of New York city lights, Venetian balconies, and London rain. The process of unlearning so many years of indoctrination was exhausting. There are moments even now where I find myself slipping. The only way, I think, is to be an active observer and critique everything put in front of me, no matter how tiring it may be. There are millions of stories that aren’t for me, ones that I am allowed to enjoy. And I have learned that if I find gaps in either Western or South-Asian stories, it is up to me to try and fill them.