On September 20, 2019, Sydney came alive. The streets brimmed with energy as 80,000 voices came together to demand climate justice at the Global Climate Strike.

The event was a monumental occasion for the environmental movement, marking an unprecedented level of public concern for climate change, the future of the Earth, and a lack of government action, but it was also profoundly important for me as an expression of my Christian faith.

The memory I have of that day is fundamentally one of community. I joined a contingent of over 350 people from the Uniting Church who brought a unique motive to the protest, a belief in God, and a call to care for creation.

Our participation in the global climate rally is not dissimilar to many other experiences I have had with my Church congregation. We have marched at Mardi Gras, Palm Sunday, International Women’s Day and against the Religious Freedom Bill. We’ve joined the nationwide prayer services for reconciliation before January 26.

My religious beliefs are deeply interwoven with a mandate for social justice. If I am to follow Jesus, who was himself an activist, I must accept his radical call for an upside-down Kingdom. This call is widely accepted to be one of generosity and forgiveness, but to me, it goes further. It is a call to completely upend the value systems of our time, to enact servant leadership, not domination. To put the poor first, and not just those lacking capital, but those lacking power, as the translation of one Hebrew word for “poor” — עָנִי (ani) —suggests.

In practice, this means accepting people of low social status and social outsiders. We see Jesus take this up by welcoming prostitutes, tax collectors and Samaritans (an ancient enemy of the Jewish people). In today’s context, I see this correlates to extending a hand to ostracised demographics such as refugees and people seeking asylum, people who identify as LGBTQI+ and Indigenous people.

I strive to follow this example by joining social movements that support these marginalised communities in a subversive manner, calling out the hypocrisy and inaction of our political leaders. Jesus did the same. Before his death, he stood up to the religious authorities of Israel, condemning their sanctimony. The Scribes and Pharisees taught the law but failed to practice some of the most important aspects of it – justice, mercy, and divine love. Many of our current politicians do the same, claiming to embrace diversity and multiculturalism but in reality ignoring those that do not look like them.

I feel then an internal conflict, because I hear the Church preach compassion, but often fail to see this turn to action. The Church has undoubtedly become less visionary since the time of the first Followers. I have my own thoughts about why this is, but I want to dig deeper into the story of Christianity to try and pinpoint where this shift occurred and why Christians now accept a less revolutionary version of what Jesus was preaching. For me, the role of religion is in making our world a better place for everyone, that is the vision of God’s universal love, but Christians are not always united in this outlook.

Missions, colonisation and Indigenous justice

This investigation of Christianity will begin with truth telling, because the reality is that the Church has been complicit in perpetuating falsities and injustice. Part of understanding why the Church is not a force for social change lies in its history. In Australia, one example of this has been the role of missionaries in the colonisation of First Nations peoples.

Missions, alongside reserves and stations, were one type of land grant that the government set aside for Aboriginal people to live in. They were operated by churches or religious individuals to provide housing (mainly because settlers had driven Indigenous people from their ancestral land), train residents in Christian ideals, as well as prepare them for work in largely unskilled occupations. The fundamental basis of such missions was a rejection of Indigenous culture and a belief that Western civilisation, religion, and ways of living were superior.

In his book One Blood, Rev. Dr. John Harris reveals this low view of Aboriginal society by quoting a Wesleyan missionary, who “described Aboriginal people as ‘barbarians’ to whom had been assigned ‘the lowest place in the scale of intellect’,” as well as a Lutheran missionary who “wrote that (Aboriginal people) were ‘the lowest in the scale of the human race.’”

Harris also illustrates that early encounters of Indigenous spirituality were dismissed as inconsequential. He quotes one such missionary who writes “[The Aborigines] have no idea of a supreme divinity, the creator and governor of the world, the witness of their actions and their future judge. They have no object of worship. . . They have no idols, no temples, no sacrifices. In short, they have nothing whatever of the character of religion or of religious observance, to distinguish them from the beasts that perish.”

Although not as violent as the biological assimilation promoted by Government administrators through the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, the social assimilation practised on these remote missions was still disruptive and came down to an inability to differentiate between the gospel and the missionaries’ ideals of “civilisation”. The strict regimentation and control of these homes undermined the very gospel the churches stood for which emphasises hope and grace. An inability to see God’s reflection in both Indigenous peoples and their way of life meant that missions added to the inequality of First Nations peoples.

A piece of hope that comes out of this history is the presence of the Black Church in Australia. It comes as no surprise that the majority of Australians align themselves with Christianity, but, importantly, a majority of Indigenous peoples do too. Critically, this community did not arise simply because of missionary conversion, but also because Aboriginal people had encountered the creator God long before Captain Cook stepped ashore in 1770.

Brooke Prentis, a Waka Waka Christian woman and CEO of Common Grace, explains to me that “for Indigenous people, we believe in the Creator who passed down the laws. These laws dictate who the creator is, how to care for creation, and how to live in right relationship with each other. These are ideas core to Christian faith and the biblical principles we [Christians] are called to live by.”

She also tells me that unfortunately, the Church continues to be slow on the uptake of Indigenous justice because Indigenous knowledge is not always shared with the breadth of the Church. “Part of what has happened is that Indigenous people haven’t been brought into theological teaching. This is when we realise the lens that we get taught theology through, it doesn’t have to be white, male Christian lens. Let’s look at the bible, as Uncle Rev Graham Paulson said, with Aboriginal eyes.”

Both historically and today, I see the Church reluctant at times to seek justice, resistant to the deep, institutional change that Jesus so vehemently fought for. Part of this seems to be a sense of ease and comfort, that God is there to make one feel good. However, the message of the Bible is not a comfortable one, but an agitational call to action. Jesus urges his followers to deny themselves, take up their cross and follow him.

Many Christians across the world are persecuted for answering this call. I am reminded of the shocking Easter bombings on Sri Lankan churches last year which killed 259 people. In stark contrast, most Australian Christians have never faced difficulty in expressing their religious beliefs. What then is the cost of following Jesus? For me it is giving up a life of self-advancement at the detriment of others, replacing the pursuit of money, power, security and self-gratification with a selfless solidarity with those excluded by society. This is by no means an easy undertaking, but something Christians should strive for.

Conservatism within the Church

I see a dissonance in the actions of the overarching powers of the Church. George Pell exemplifies this. Rising to prominence on a platform of conservatism, Pell consistently acted to protect the structure of the Catholic Church by silencing the many people who were sexually abused by clergy. When it was revealed that he himself perpetrated an abhorrent amount of abuse, it revealed a glaring hypocrisy—that the conservatives who have the power to define what the Church is preach love and care whilst institutionalising and covering up a crisis of abuse. Not only is this outwardly harmful, but these behaviours alienate so many from the Church. I say that most Christian Australians can practice their faith without persecution because not all actually can. Ironically, it is the Church that is pushing away many of the faithful that wish to be there. Survivors of abuse, people identifying as LGBTQIA+ and women seeking bodily autonomy are often denied a place at the table through these actions. It is the Australian Christian Lobby doing this also, it is the Christians on campus at USyd who put up signs on Eastern Avenue telling women that they are murderers.

Is this not the complete opposite of Jesus’ message? That no matter who you are, you are welcome in God’s Kingdom, not only, but most especially those that are vulnerable or marginalised? I believe the Church fails Christians every day when it judges the worth of others, something only God can do.

Activism within the Church

The other side of this investigation is understanding the truly uplifting work that Christians do. I see many Christians in my community and across the Church answering this call, dedicating each and every day towards social change. Returning to the radical way of Jesus is about telling these stories and following their example.

David Barrow, Lead Organiser of the Sydney Alliance, tells me, “both historians and organisers understand that deep and long-term sustainable change in this country, many of the biggest things we take for granted often have two progenitors: one, the church and the other, the union movement. The union movement was built by Irish Catholics, atheist socialists, and Methodists. The campaign for Aboriginal rights, against nuclear arms, peace in Iraq, refugee movements, all of these issues have often been led by churches or Christians.”

One of these untold stories is that of William Cooper, who Brooke points out as someone not many Australians, let alone Australian Christians have heard of.

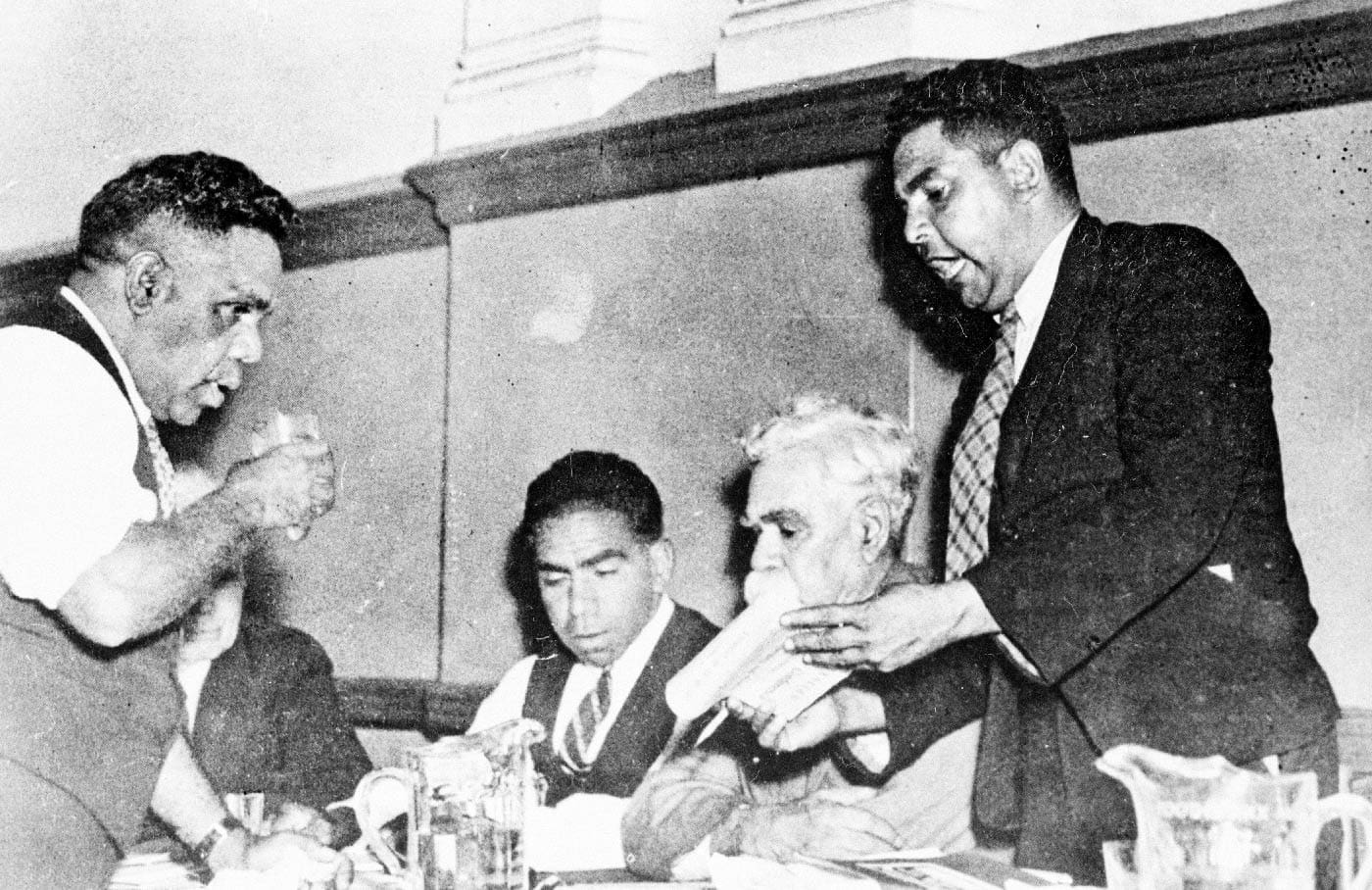

Born in 1886, Cooper was a Yorta Yorta Aboriginal man of faith and a prolific activist. In 1936, he set up the first January 26 Day of Mourning protest, which would soon become Aboriginal Sunday, an event observed in churches before Invasion Day. The tradition laid the roots for what is now NAIDOC week. Cooper was also the only private citizen in the world to protest Kristallnacht, the outbreak of Nazi Germany. He led a delegation to the German consulate in Melbourne to hand them a letter denouncing the violence carried out by Hitler’s regime, a fact which is now celebrated by the Jewish people.

He was “this incredible Aboriginal man who was driven by a Christian faith,” says Brooke. “When we don’t tell these stories, we miss out on the contribution to Australian society.”

Sadly, Cooper did not see his call for citizenship answered in his lifetime as it would take 30 years after passing until Indigenous people had citizenship rights.

This ground-breaking activism should be an inspiration for Christians. Sadly however, when the Church focuses on fighting against things like marriage equality and bodily autonomy, it undermines the important work of people like Cooper. It is also an example of how Indigenous people, including Indigenous Christians, are still not equal in the eyes of the Church.

I turn to David Barrow and Brooke Prentis for inspiration, because for me, they are current examples of faith being put to action.

As Lead Organiser of the Sydney Alliance, David sees himself as a “catalyser agent that works with partner organisations to come together for common good,” which at the moment is a campaign for a fairer deal for international students and migrant workers who have been left out of Jobseeker payments. The Alliance also operates campaigns for housing, people seeking asylum, affordable renewable energy and work-life balance and draws its partners from across civil society including unions and other religious organisations such as the Muslim Women Association and the NSW Jewish Board of Deputies.

When it comes to his faith, David says “Jesus Christ was a prophetic messiah and saviour but as a man a carpenter and a community organiser. And even if Jesus wasn’t, Paul definitely was. Fundamentally, the story of going from the periphery to the centre of power is the story of the New Testament.”

The challenge David puts to his community “is recognising that faith is not private. Believing in Jesus is to follow Jesus in your life. If that’s the case, you follow throughout your week. Not out of a sense of punishment, not about being God’s good books or brownie points for heaven, but a deep, intrinsic sense of purpose.”

Brooke’s work at Common Grace sees her lead a movement of over 45,000 Australian Christians which focuses on justice for people seeking asylum, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander justice, ending domestic and family violence, and Creation and Climate Justice.

She also coordinates Grasstree Gathering, an annual congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Christian leaders, a vision of Aunty Jean Phillips. I ask about Aunty Jean Phillips and how the leadership of elders in her community continues to drive her.

“I met Aunty Jean Phillips at the first Grasstree Gathering. She is still serving with over 60 years of ministry, often with no pay. She taught me to be present in and serve my community. She has developed other Christian leaders as well as extended a hand in friendship to non-Indigenous Christians to come on the journey with us. That was a huge inspiration and example to me.”

“Those elders that have gone before me, they never got to see the things that they took action for, prayed for, achieved in their lifetime. So there’s a responsibility for me to see some of the fruits of their work in today’s Australia. I have to do what I can to honour their legacy as well as create a better future for the next generations”.

Thankfully, there is a growing response to the leadership in these positive expressions of faith. When I ask Brooke about how faith drives her in her vocation, she answers, “someone once asked that question, effectively why do you do what you do, and I said ‘because I know that God is up to something, and I want to be a part of that.’”

There is an appetite in Christians to make a positive change. The stories of Christians both past and present lead a call to the wider church, to do compassion, not just preach it.

As David says, “it always starts with the people. If everyone is a child of God, then you start there. Then you realise, refugees are images of God, people seeking asylum are images of God, people affected by punitive drug laws (that don’t lead to recovery) are in fact reflections of the divine. That if God’s creation is a reflection of the divine, then why would we let it be destroyed?”

If we want society to know us for the deep love we have for everyone, we must show that through our actions. Jesus was undeniably on the side of the ignored and oppressed, even when this threatened his reputation. It is time for the whole Church to join him.