Since Venice established its first biennial exhibition of Italian art in 1893, we have seen many different iterations of biennial exhibitions of national art forms, in the form of the biennale. A biennale is an international art festival which occurs every two years, and curates artworks that culminate in a showcase of the diversity of the region it is exhibited in. With the Venice Biennale as a blueprint, the biennale’s goal is to provide a platform for contemporary art practices which are underrepresented in museums and galleries. This has meant that many other instances of biennales have deviated from the Venetian model which has become the same institution it used to offer an alternative to. For instance, the establishment of the Havana Biennale in 1984 was an expression of the amount of art being made in the Global South that had gone unrecognised.

Today, the hundreds of biennales around the world function in many different ways, meaning the relation and artistic exchange between them has evolved in very political forms. A biennale, as Peter Sloterdijk would argue, has the ability to reproduce different nations and their socio-political relations in a gallery space. This political nature of course brings with it the state’s economic position to the arts; as a market, as patronage, and as something for economic gain. The Biennale of Sydney, first established in 1973, came under fire in 2014 when artists boycotted the 19th iteration of the Asia-Pacific region’s longest running international art festival due to such controversial economic ties.

In 2014, Libia Castro, Ólafur Ólafsson, Charlie Sofo, Agnieszka Polska, Sara van der Heide, Nicoline van Harskamp, Nathan Gray, Gabrielle de Vietri and Ahmet Ögüt withdrew their work from the festival due to the Biennale of Sydney’s ties to Transfield Holdings, a company that held an investment in Transfield Services. These six artists withdrew their work due to Transfield Services’ contract with the Australian Department of Immigration to work on the detention centres on Manus and Nauru. An additional 41 artists wrote an open letter to the Biennale of Sydney urging them to reconsider their partnership with the company embroiled in the human rights violations of the Australian Government. While the boycott was successful and ties were cut with Transfield Holdings, this incident calls into question the true function of the Biennale internationally. Can it truly be a platform for artists to present subversive art forms and meaningfully critique borders and the idea of the nation?

In 2018, under the Artistic Directorship of Mami Kataoka, the 21st Biennale of Sydney: SUPERPOSITION: Equilibrium & Engagement did not centre on any one theme, but instead attempted to present a variety of different concerns. Borrowing the term “superposition” from quantum mechanics, its goal was to elaborate the duality and paradoxical ways that humans inhabit Earth through the artworks of 69 artists from 35 different countries. One such artist was Ai Weiwei, whose practice focuses on social injustices with specific attention given to refugee rights. The work of Weiwei fit within the overarching theme of the biennale but in an incredibly troubling way. The works seem to be at odds with both the international art festival’s partnership history and the general problem with biennales: these biennial exhibitions seem to uphold the idea of the nation through mimicking its borders rather than offering a platform to deconstruct them.

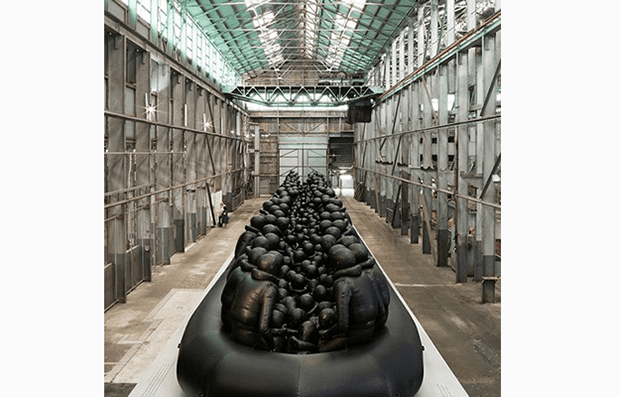

Law of the Journey (2017) featured a 60 metre-long boat filled with refugees made from rubber manufactured in a Chinese factory which also constructs vessels used by refugees seeking asylum in other countries. The work is certainly dual and paradoxical. On the one hand, the larger than life piece, meant to make the viewer feel the monumental scale of the global refugee crisis, is troublingly haunted by the biennale’s prior complacency on cruel mandatory detention. On the other hand, its positioning in the biennale is also troubling, as the exhibition focuses on going against Euro-American centric visions of contemporary art while acting within the Euro-American centric visions of nations and how they should be divided. In its attempt to draw Australian artists into the cultural stream, the schematic system of the Biennale of Sydney is admirable, but the festival’s own role in the nation building project of Australia is rarely critiqued and the works that are exhibited in them seem to be “superpositions”; dualistic and paradoxical, critical and yet complacent, outside of the nation and within it.

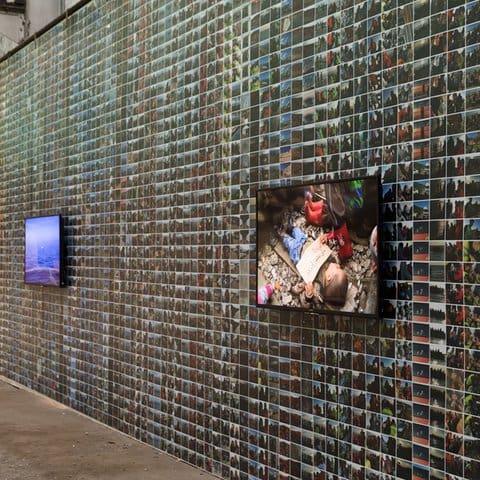

In another work, 4,992 Photos Relating to Refugees, which lines the gallery’s walls with photos taken by Weiwei on his iPhone during the filming of his documentary Human Flow. What does it serve to plaster the faces of people who have been or would be denied access to our country in an exhibition which has both been literally tied with the forces that prevent them from seeking safety in the past and fundamentally tied to the idea of the nation? The inclusion of this artwork may seem like a protest levelled against the government, and while it does make a statement, why can’t art go even further in critiquing the borders that colonialism has so verdantly drawn? Why can’t it go beyond established arts institutions and exhibitions and instead find its voice in interregional conversations? Art has a real possibility to be a tool for change, a tool that is not being used to its full potential.

Perhaps the thing that prevents the work from successfully critiquing social injustices is the sense of fixed place that is inherent in the Biennale structure. Kataoka asserts in her post-curatorial statement that the “significance of a biennale does not merely consist of gathering existing artworks in one place.” While it is true that the artworks exhibited in a biennale are made precisely for the biennale, the argument that they are not made for one place is not necessarily true. If this were true, the idea of the biennale would not be so rooted in the idea of the nation. Would the art works of Ai Weiwei not function better as political critique through a more collaborative, independent and interregional exhibition?

Perhaps the name “SUPERPOSITION” is more accurate than I give it credit. All future iterations of the international art festival will have to grapple with the paradoxical idea of a biennale, which at surface level, seems to be an encouragement of international exchange of art and ideas but, when interrogated, is exposed for its unbreakable link with the idea of the nation. As governments profit from the subversive ideas of artists in national displays of “difference and diversity,” one could say that the biennale plays a very vital role in nation-building, a role that artists should critique from the outside of the biennale, rather than within it.