The psychiatric ward has always been portrayed in film as a scary place. Whilst hardly the ideal place to be, film’s fascination with the insides of its characters’ minds – and the psychiatrists that try to get inside – effectively others the world of mental illness. The problems with the depiction of mental illness in film are extensive, but tracking historical and recent portrayals of psychiatry in film are useful in highlighting the particularly problematic attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatry as a whole.

Psychiatrists don’t like to use the word crazy, but they are themselves often portrayed as such.

The demonisation of psychiatrists as individual characters feeds off a stigma that they are manipulative, themselves unstable, intimidating or something to be afraid of. These range from professional indiscretions, such as having inappropriate relationships with patients or prescribing untested medication, to going mad and becoming diagnosed psychopaths themselves. The invocation of psychiatry as imbuing some sort of character depth or darkness is as harmful and reductive as assigning a nondescript mental illness to a morally ambiguous character, like the Joker.

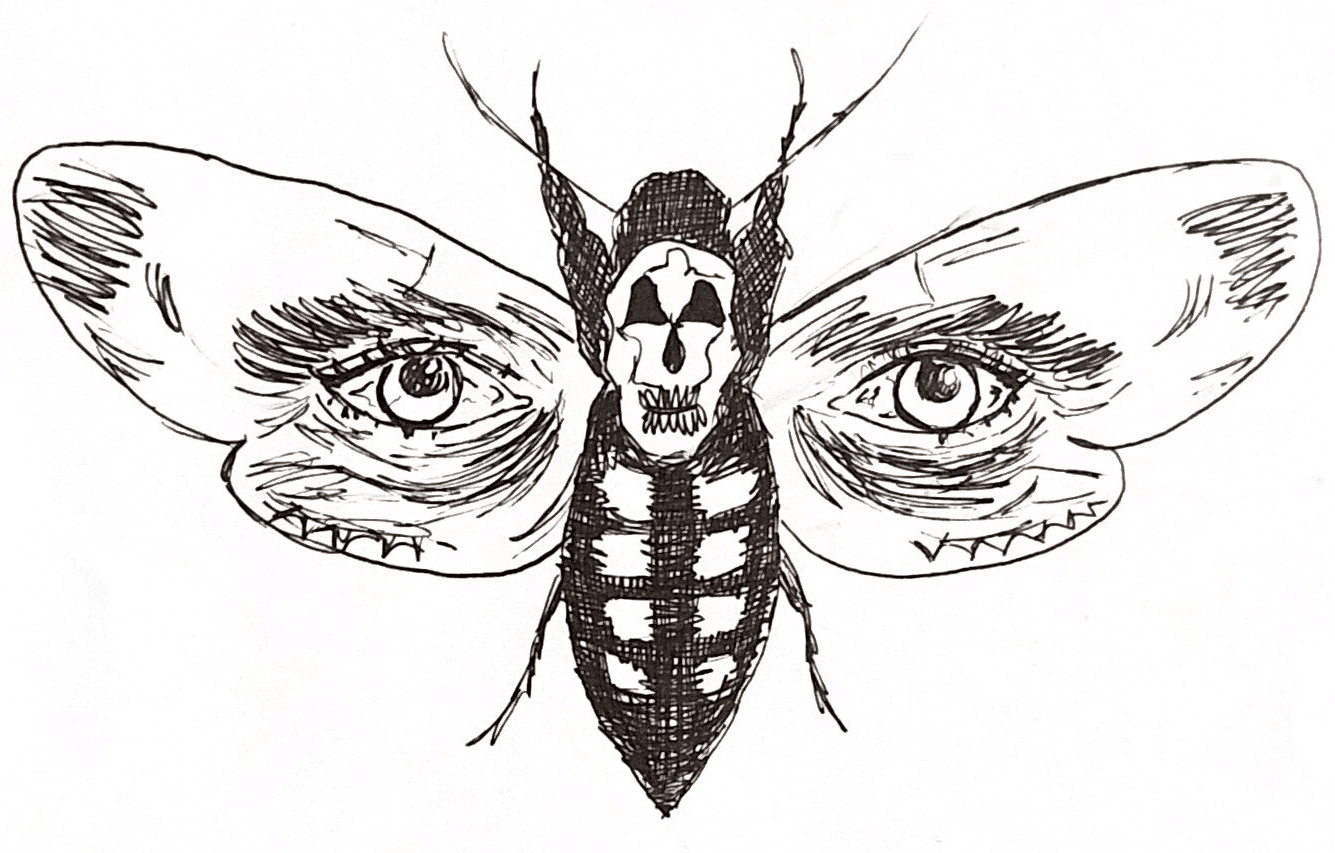

Psychiatry occupies a space in the collective cultural imagination adjacent to mental illness and psychosis, because these concepts are inherently part of its discipline. But their conflation instils fear and entrenches a preconceived resistance many may already have. Hannibal Lecter scares us. Harley Quinn amuses us. From the highest to the lowest brow of cinema, the idea of a psychopathic psychiatrist is ripe for exposing our internal contradictions. But juxtaposition should not be mistaken for complexity, and filmmakers should be careful with how they invoke and incite fear or parody in their portrayal of psychiatrists.

In Side Effects, starring Channing Tatum, Jude Law and Rooney Mara, Dr Banks prescribes an experimental drug that leads to side effects including stabbing someone to death whilst apparently sleepwalking. Throughout the film, characters are threatened with electric shock treatment or incarceration in the mental ward, psychiatrists commit securities fraud to manipulate stock prices via the prescription of medication and there are discussions of how to fake psychiatric disorders. Whilst it is interesting to explore how perverse incentives operate in the medical profession and look into the personal lives of our doctors and their patients, if it is not done well, what filters into the mainstream can infect perceptions negatively.

Further, a depiction of outdated practices can deepen clinical distrust amongst everyday audiences. From Freud’s avid cocaine addiction and the concept of penis envy, to Jung’s theories of the unconscious and the propagation of electroshock conversion therapy in the mid-20th century, suffice to say that psychiatry is an imperfect discipline. But since One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, psychiatry has developed. Lobotomies are no longer performed. Even the depiction of electroconvulsive shock therapy as an inherently harmful practice lacks nuance and likely makes patients less likely to opt in.

Inaccurate psychological methods are also often appropriated as forming part of psychiatry in film. For example, the use of hypnotism to trap Chris in the sunken place in Get Out is performed by his girlfriend’s mother, a psychiatrist. Mention of her profession immediately stirs intimidation in him, and an ominousness suddenly surrounds her. This unnecessary characterisation as a psychiatrist, which bears no relation to hypnotism, plays on tropes familiar to the horror genre, a nod to The Silence of the Lambs. It is unnecessary because it delivers no commentary. It is merely designed to trigger and reinforce a negative association.

Films that reframe or challenge diagnoses of established disorders as a plot point can also exacerbate distrust of clinical diagnosis and ultimately stigmatise seeking professional, often institutionalised, help. In Split, a man with dissociative identity disorder is portrayed more or less as a monster. In its follow-up, Glass (a title that directly plays on the concept of the disordered being broken), the characters that are detained for delusions of grandeur are actually revealed to be superhumans. Whilst admittedly fun to entertain, when the vindication of delusion becomes a pervasive trope rather than a unique narrative, its harms extend far beyond poor screenwriting. To give credence to a reality that is threatened by a disorder and to those suffering from intrusive thinking confuses the ways in which we should treat and perceive those who are mentally ill.

In Unsane, a woman is involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital by unknowingly signing a consent form and then having multiple physical altercations or attempts to alert staff of her plight. In the film, her being stalked is perceived as a delusion by the medical professionals. This framing is perhaps dangerous, because the validation of psychotic delusion leads to counterproductive questions that invite audiences to challenge the diagnosis of similar hallucinations in the real world.The notion of involuntary commitment as an insurance scheme, as a pernicious act undertaken by untrustworthy medical professionals, further cultivates distrust in the psychiatric system. However – interestingly – as in Side Effects, these narratives seem to intersect with problems with the healthcare system in the United States, most glaringly the financial incentives of big pharma. Whilst this kind of exploration should be foregrounded, it need not be traded-off with faith in our actual doctors.

To the extent that the media significantly shapes our perceptions, it is dangerous to popularise negative depictions of a field that already suffers from stigma, even and especially if there are commercial incentives to do so. Stereotyping in popular discourse is generally quite harmful, but the commodification of mental illness in the film industry is particularly damaging where stigma is a huge barrier to seeking help. Approximately 18% of Australians received mental health-related prescriptions last year and in the wake of COVID-19, a mental health crisis, particularly amongst young people, is incredibly likely. It is paramount that psychiatrists – who are also essential workers – are portrayed responsibly. At the very least, characters who take on the profession should be developed in the way those they embody do their jobs; with compassion, depth and the most up to date medical knowledge.