If you, like me, frequently use the Spotify Private Session feature to go and listen to corny movie soundtracks in fear that your Spotify friends will cancel your music recommendations and taste – well, then I’m glad I’m not alone. In the culture of surveillance and the merging of public and private digital space, we open up small nooks of anxiety-inducing indulgence and shame for “guilty” pleasures. Whilst I believe that no one should feel guilty for any pleasure they feel – perhaps this can’t be a universal claim – the subjectivity of music and why we love certain music is a question that remains difficult to answer and hard to admit.

As the Bill Clinton Swag Meme continued to trend during the period of self-isolation and quarantine, I felt a growing knot in my stomach as I struggled to find the perfect curation of four critically-acclaimed albums that I could credit for polishing off my outstanding and in all ways, elite (sophisticated, superior, better than you, etc.) sense of music.

However, there was only one album I could think of that would encapsulate what music has significantly impacted and shaped my music taste, albeit a social sacrifice that I was hoping would bring all my followers to their senses to realise its goodness and influence. The Twilight Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (2008), despite the actual film’s commercial success but underwhelming critical and cultural legacy, has miraculously stood the test of time and can be credited as a breakthrough for a number of successful 2000s and 2010s indie and alt-rock bands.

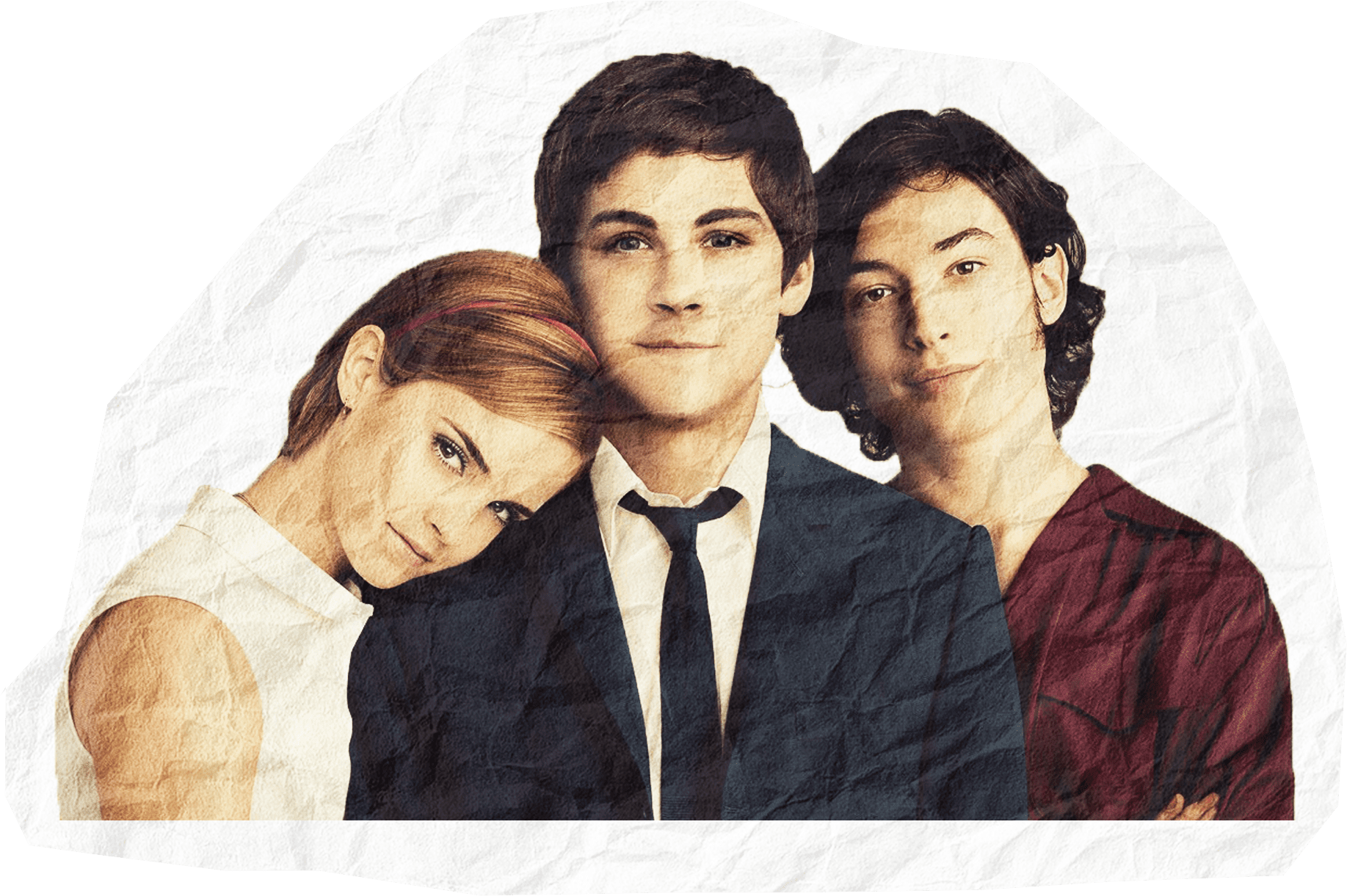

It would be ignorant to say that every teen movie has a flawless and perfectly curated soundtrack, though a few stand out over the past few years. Specifically, films such as Jonathan Levine’s Warm Bodies (2013), and iconic television dramas like Gossip Girl (2007-2012) have soundtracks which introduced a blend of new indie artists to a more commercial ground.

Without placing too much credit on the shoulders of any of the said narratives and plots, the aforementioned films demonstrate the true art of music supervision and curation; a craft that can be credited to those who seem to be able to dissect, describe and prescribe the perfect soundtrack to the right moments. Initially booking bands to play at the University of Illinois, then later working as music supervisor for producer Roger Corman, Alexandra Patsavas seems to have been part of the Midwest American indie scene before I knew it existed. Since founding Chop Shop Music Supervision in 1998, she and her team have accumulated quite the impressive resumé, working not only on said soundtracks, but also on Mad Men, Grey’s Anatomy, The O.C., and 2010s films, The Perks of Being A Wallflower and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (Chop Shop, 2020).

For those less familiar with the soundtracks of each of these films and series’, an easy explanation would be that Chop Shop Music Supervision is the name behind your music taste and the songs you associate with growing up – the reason you probably listen to Death Cab for Cutie or Iron & Wine. A certain timelessness is discovered in her work and that impressively showcases artists like Radiohead alongside Paramore, and then John Waite alongside the Black Keys; a number of these soundtracks marry artists genres apart and push the cinematic image and narrative forward.

Unlike the more commonly discussed art of scoring films, music supervising involves the collaging of various pre-existing musical works. Less guided by conventional tropes, music curation dabbles in individual works of artists that create mood and feeling that strictly exist in those few minutes. Patsavas has made a name for herself over these past few films as a tastemaker of the indie genre that’s guided more by the sounds that aren’t heard than those that are.

An observer of filmic needs, her selections give movies the oomph necessary to push that mile ahead, channelling the intimacy required for Twilight, humour for Warm Bodies, and mix of Manhattan-Brooklyn hipness to makes you recall tracks like Peter Bjorn and John’s ‘Young Folks’ when meeting it-girl, Serena van der Woodsen in Gossip Girl’s pilot episode. In an interview with Fast Company, Patsavas stated, “Of course you think of a cohesive album, but none of that works unless the songs tell the story… The first time the audience experiences the track, it’s in the context of the movie”.

It’s interesting that Patsavas’ breakout supervision was for Twilight, a film notoriously (love)hated by film buffs, purged by old fans and even ridiculed by its own star, Robert Pattinson. Though, it is exactly that hatred that makes the soundtrack even better in comparison and maybe, the only agreeably ‘redeemable’ quality of the film. Upon examining the soundtrack, it’s clear to see how the selection was most probably influenced by its iconic rural Washington state setting. It could have just as easily been titled as a ‘Sounds of Isolation’ compilation album fit with a pine tree album cover – not an uncommon thought, it seems. The connection between indie music and the foggy, mossy setting of Seattle is one that’s been discussed by many music geography scholars and journalists – why is it so difficult to separate gentle folk music and garage rock from this particular region of the United States?

Discussed by Thomas Bell in his article Why Seattle? An Examination of Alternative Rock Culture Hearth, he pulls apart the idea of the “Seattle sound”: An “element congealing the Seattle groups into a scene if really a sound, is the musical ‘honesty’” (Bell 1998, 38). The whole idea of musical ‘honesty’ seems to be exactly what’s amplified through highlight tracks featured on Twilight: ‘Decode’ by Paramore, ‘Eyes on Fire’ by Blue Foundation, ‘Supermassive Black Hole’ by Muse. Grant Alden and Jeff Gilbert say, “Seattle is not Los Angeles or New York. It’s not a place where things happen and the world notices. It’s at the far edge of an enormous country hemmed on all sides by mountains and water. It’s beautiful, remote and claustrophobic” (Alden & Gilbert in Bell 1998, 39).

A sense of isolation is consistently amplified throughout the tracks on the soundtrack, utilising recording techniques of heavy reverb, quiet whispering and humble guitar plucking that echoes the danger that the film’s setting of Forks, Washington, presents. Though the exclusion of perhaps the most well-known Seattle band, Nirvana, seems to be a curious choice that indicates a greater creative intention to stick towards smaller artists; artists on the outskirts of mainstream culture, lurking and waiting for someone daring enough to step forward and curate them into the perfect compilation.

In the case of Warm Bodies, the music curation exists with a generic function rather than geographic – probably out of necessity for a Romeo-and-Juliet, zombie-rom-com. The soundtrack consists of a heavier ‘80s sound, focusing specifically on romance and acoustics, undoubtedly to contrast against the otherwise more depressing post-apocalyptic setting. Notable mentions of this genre curation include John Waites’ ‘Missing You’ and Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Hungry Heart’. Ordinarily associated with the heavy rotation of the Smooth FM sound, the music functions for a different and more meaningful purpose here. A growing sense of nostalgia is achieved in its use in Warm Bodies, drawing viewers into the record-playing, knick-knack-collecting, generally endearing zombie character of R, who in the opening scene reminisces about the human lives of zombies lingering at the airport to Jimmy Cliff’s ‘Sitting In Limbo’.

In an iconic scene from the film, R is broken-hearted and being consoled by his friend M (I promise that most characters in this film have a name longer than a letter) who encourages him to pursue his romance and also indicates towards a growing emotional change among the zombies; they’re becoming more human. As R asks for their help reaching Julie, the scene cuts to the group of zombies against a morbid backdrop of destruction, shuffling determinedly along to the hilariously juxtaposing, searing guitar solo in Scorpion’s ‘Rock You Like a Hurricane’. A general focus on overall cohesion is the element of prime importance when stringing songs together, and you would think that this is more easily done by picking songs from a similar era, complementing and leaning on the musical similarities and cultural substance of one another. Patsavas presents a curious case against this. Cleverly accenting all the comedic beats of the film, it’s impressive to be able to integrate indie artists like Bon Iver and The National alongside more timeless acts without a jarring contrast.

The case for Gossip Girl, is, again, quite different. This time, the supervision dictates the relationships between the characters, balancing themes of fame, glamour and prestige. Gossip Girl is, for the most part, a teen-drama that preys on the spectacle of New York City celebrity culture and elitism that seemingly resides in four Upper East Side families, narrating their Met Museum yogurt-and-granola morning routines and equally pretentious high school concerns. While this explains the prevalence of more poppy club tracks, that also admittedly sound ten times worse retrospectively, the indie features seem to draw from the hipster, Brooklyn upbringing of character Dan Humphrey, who seems to be tormented and taunted for his apparently “inferior”, off-the-island upbringing for the full six seasons. Unsurprisingly, Patsavas found the perfect playlist.

Though, unlike Twilight and Warm Bodies, upon relistening to the ‘Gossip Girl Soundtrack Season 1-6’, it becomes almost painful pairing JAY-Z back-to-back with Washington Social Club, then Flo Rida with Cold War Kids. The result ends more as a mishmash, people-pleasing playlist that feels all too common at primary school discos. Yet, Patsavas makes these songs work in the context of the show; as viewers we quickly realise that the presence of pop music only exists to frame the superficial personalities presented in certain characters. The more honest substance of ‘reality’ that carries the actual story is instead, humbly complemented by the unique originality of indie artists and songs.

With this in mind, it’s easier to understand why music from my teenage years seems to have a timeless quality that settles into a sticky nostalgia. This could partially be due to the fact that young adulthood is a time where we ‘come to our senses’ and begin to develop likes, dislikes and learn. A romanticised notion that’s only affirmed in the fact that a lot of the tracks from Chop Shop Supervision still hold a sense of first-time listenability. Anyone who has watched a teen flick in the past five years may struggle to find the same success (though some more recent exceptions may include Beautiful Boy (2018), Eighth Grade (2018), Booksmart (2019)). Though perhaps, it has more to do with the reputations of the bands since their features in these films and television series’. Now critically-acclaimed and reviewed by publications like Pitchfork, The Atlantic and Rolling Stone, artists like Feist, The National and Vampire Weekend have become defining figures of 21st century indie and alt-rock that carry way beyond the late 2000s into the late 2010s.

Patsavas’ curation wrapped smaller indie bands into commercially-consumable packages of narrative, plot and sprinkled them with renown and timeless musical works from past decades. If anything, it’s a clear example of the ‘golden mean’ of musical and production intentions in films and television. The emerging beauty of film, television, streaming and independent production lies in the growing avenues for rising artists to reach audiences – “That’s the new way with the digital age” says Patsavas.

Without judging the quality of a soundtrack based merely on the critique of the overall film, there’s something to be celebrated in a good playlist, even away from the screen. What becomes apparent is that despite the mediocre critical reception of Twilight, Warm Bodies, Gossip Girl and most other works supervised by Chop Shop, the legacy of the featured music has forged a kind of subliminal connection to these fictions – in turn, the fictions to the music – that’s eternally romanticised in Generation Z teenhood.