In my opinion, Edward Said’s exalted standing among the intelligentsia of yesterday, today and tomorrow is as illustrious, legendary and marvellous as his prose, intellect and charisma. One only needs to read his Orientalism to understand the immense impact his scholarship had on the academic fields of post-colonial study, literary theory and cultural criticism.

However, to a young twelve-year-old Mahmoud growing up in Fairfield, Western Sydney, those grand academic terms meant just as much to him as his homework; that is, not much at all. Rather, my first experience of Edward Said came not from his magnum opus, or his enlightening essays or even his consensus busting New York Times pieces. In fact, I was first exposed to Said’s prose in his Homage to Joe Sacco where he praises a medium I knew far more than the intricacies of post-structuralism and post colonialism: comic books.

Now, I very well understand that Said specifically praises Sacco’s remarkable comic Palestine, which beautifully explores the plight of the Palestinians, and does not entirely engage in a general celebration of the comic book medium. Yet the first half of his homage was an impeccable description of what made comic books so perfect. Comic books with their ‘untidy, sprawling format’ and ‘the colourful riotous extravagance of their pictures’ were a radical way of making sense of the world around me: a shabby Western Sydney suburb.

‘I don’t remember when exactly I read my first comic book, but I do remember exactly how liberated and subversive I felt as a result.’

When reading Said, I tend to feel lost. Said’s vision and intellectual foresight is so sharp, it is almost impossible to one-up his writing or experiences. However, unlike Said, I do in fact remember the first comic book I read: Alan Moore’s, Dave Gibbons’ and John Higgins’ Watchmen. I also remember exactly how I felt: liberated and subversive.

You may be wondering how a twelve-year-old managed to get access to such gritty and dark series. Well, Fairfield Library was a rather busy place and the librarians could only focus their attention to the onslaught of demands coming their way. This provided a few avenues to wander over to the adult section and read Moore’s legendary work in the privacy of a chaotic community centre.

The panels, the non-linear structure, the darkness of this world on the brink of World War III was such a liberating experience. These heroes of Watchmen were flawed, each with a morally incomprehensible view of the world, and challenged the moralising I detested from community leaders, politicians and teachers. The existentialism and consequentialism the comic book illuminated was subversive. It was by virtue of a neon coloured comic book that I had begun to think about what power, political action and thought could bring about in societies on the brink of collapse. There was not going to be a perfect Superman that would better my working-class community. There was only going to be individuals, warts and all, doing what they thought was best. That lesson had a two-fold advantage: you would not hold individuals to an unfair standard, and you would not be disappointed once their veil of idealism faded.

‘Comics played havoc with the logic of a+b+c+d and they certainly encouraged one not to think in terms of what the teacher expected or what a subject like history demanded.’

I distinctly remember the first time I had seen what the Arab Spring had entailed. My father and I had attended a typical consultation with my local GP who was of Egyptian descent. Children of the Arab diaspora know that when two Arab men are in close proximity of each other, a discussion pertaining to politics is a virtual certainty. The GP had told me to wait outside so he could show my father images of the Egyptian Revolution. Fortunately (or unfortunately), the door was not entirely shut, and his computer screen faced the room’s exit. I caught a glimpse of Guy Fawkes’ mask as well as bloodied protestors of all ages.

I had seen that mask before. Where? Fairfield Library. As soon as the session ended, I rushed to the library and picked up Books 1, 2 and 3 of V for Vendetta. That comic book epitomised the tension between anarchism and fascism in a way that my history teacher would disapprove of. It was not academic or pristine or ‘neutral’ if there ever was such a source of such quality. It was through this comic book that I had began to engage with the Arab Spring, the political economy of the Middle East and the lived experiences of the refugees that had called Fairfield their home.

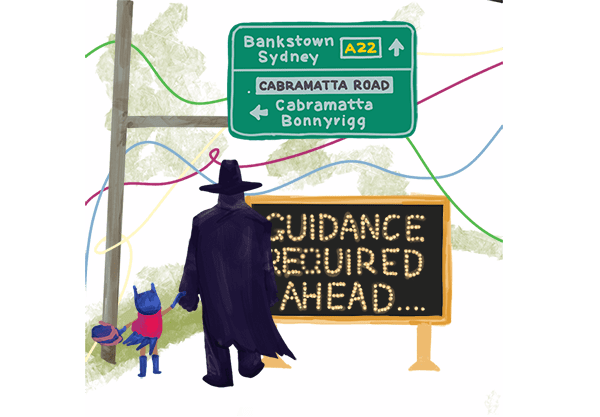

This was not a logical process. There was nothing orderly about a superpowered anarchist revolutionary within the confines of a dazzling comic frame inspiring a process of such political superimposition. But alas, that is what is so grand about these pieces of eye bursting art: they did away with the logic of ‘a+b+c+d’ that policed, and continues to police, my mind.

“I knew nothing of this then, but I felt that comics freed me to think and imagine and see differently.”

There was a mundanity in my life that was hard to escape. To cope, I would daydream drawing upon Doctor Who and Spider-Man comics. I would imagine I had a Tardis, flying through time and space with the Doctor. Those glorious panels of daleks, stars, planets and technological behemoths were the building blocks of mental adventures that allowed me to think, imagine and see freely. Comic books vitiated the structure education instilled in my mind.

Even beyond the fun of space and time, these comics with their outrageous art and stories were an avenue where I could experience the vicissitudes of life. Fairfield was Queens. Peter Parker was me. In my daydreams I would collect the wisdom of a grassroots hero who was honest, plain and battled with the day to day struggle that is adolescent life. The fact I had learnt of the nobility of struggle from a teenager who was bitten by a radioactive spider is, in my opinion, cringey as it is endearing.

All in all, there is no logical link between Edward Said, comic books and life in Western Sydney. But what better way to honour comic books then by playing havoc with logic of a+b+c+d? Is it not this that makes comic books an affair of liberation and subversion? Is it not this which inspires us to think, imagine and see differently? In a world where policing extends beyond the boys in blue, where policing of all forms pierces its way into our psyche and our creativity, perhaps we may benefit by drawing on what makes comic books, in the words of Said, ‘a hugely wonderful thrill.’