Yabun Festival, the largest one-day Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander festival in Australia, was held on Tuesday. Coinciding with Invasion Day rallies on January 26th, the festival provides a space to celebrate First Nations cultures’ survival and resilience through music, dance, art, and oration.

Typically an in-person affair, Yabun 2021 was live streamed due to public gathering restrictions. Nonetheless, the energy at this year’s festival, as well as the hard work of all organisers, creators and leaders involved, was unparalleled.

While Honi editors were busy doing coverage for the Invasion Day rally, I snuck out to attend two of Yabun’s speaker panels: Love and Success. Here are the key insights from those discussions.

What ‘love’ means for mob on Invasion Day

The Love panel, moderated by Ken Zulumovski Hon DHSc, Gubbi Gubbi man and founder of Gamarada, explored what ‘love’ meant for the speakers as First Nations people on Survival Day.

William Trewlynn, Nucoorilma and Dunghutti man, spoke about his work as Founding Director and CEO of BlaQ Aboriginal Corporation.

He explained that after witnessing the harm experienced by queer Blak people in Sydney, many of whom have come from rural and remote areas looking for a safe environment, he wanted to create a space where “queer blackfellas are speaking for ourselves and not being spoken for.”

“This is a really hard and complex space” he said, noting that he didn’t necessarily ‘love’ his job in the typical sense. “But I have to take it with a grain of salt and understand that we’re doing this because we want to see betterment for our people.”

Of course, while ‘love’ might mean different things to different people, the concept itself may not necessarily translate across languages and cultures.

Professor Jaky Troy, Ngarigu woman and Director of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research at Sydney University, spoke about the limits of applying our language of ‘love’ to First Nations cultures.

Saying that she wasn’t quite sure how she would say ‘I love you’ in Ngarigu, she explained that for her, using Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages in itself was an act of love.

“In using Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, we’re showing love of Country. They embed you on Country. They give you a sense of place and of people on Country.”

She also pointed out that her language is “based on deep, complicated ways of talking about human relationships that make a place for everybody.”

“We don’t strongly gender things, we don’t force people into one kind of sexuality or binaries that the English language insists on,” she explained. “In our languages it is still embodied that we had a connection to everything around us.”

This mutuality of love and connection to Country was further unpacked by Pastor Ray Minniecon, a Gubbi Gubbi and Gurang Gurang man who has worked with the Stolen Generations for much of his life.

Coming from the other side of the 1967 Referendum, Minniecon knew what it was like to live under Aboriginal Protection Acts. “You grow up in that trauma. It just becomes natural and normal parts of your story,” he explained.

He reminded audiences that traumas live with First Nations people to this day, and so “the word ‘love’ is an alienated word for someone who has been forcibly removed.”

However, Minniecon spoke of experiencing Mother’s love through Country. “There are spaces and places on Country here that just love you — or show you what that love is.”

Recounting his time in the Jarrah Forest, he said: “When I was in there, that’s when I experienced the mystery of what we call love, because it was just there. You’re sitting in it. You’re being part of it.”

“It’s not about the action or activity of love, it’s just about being who you are.”

Talking about ‘success’ after 233 years of invasion

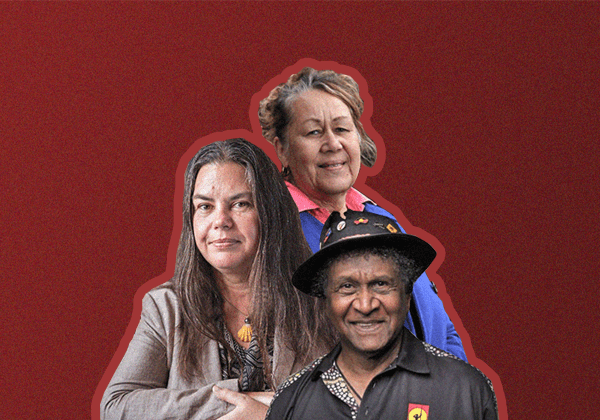

The Success panel, moderated by Lola Forester, Yuwibara/Australian South Sea Islander woman and journalist, discussed how we could talk about ‘success’ after centuries of colonial violence.

Aunty Norma Ingram, a Wiradjuri Elder who has worked with Aboriginal communities for over 35 years, spoke of ‘success’ as recognition and truth-telling.

She recounted her time growing up on a mission, attending Sunday school and having no electricity, radio or television. “Quite frankly, whilst I was on the mission, I felt safe because I was with my family,” she said.

“But I still didn’t see how the Welfare Act controlled us. And so many years later when we did leave the reserve…we began to see how controlled we were, and saw it in a different light.”

This experience is one of the main reasons Aunty Norma became an educator, teaching Indigenous and non-Indigenous people about her culture and histories.

“Success is when the whole of Australia knows, understands, learns and accepts who we are as Aboriginal people and our rightful place in this country” she said. “I shouldn’t have to go anywhere and not be Aboriginal, because that’s who I am.”

The importance of truth-telling also drove Wok Wright, Anaiwan, Dunghutti and Gomeroi man to start the Aboriginal hip-hop band Street Warriors. Speaking about his early days working with communities, he noticed a severe disconnection between young First Nations people and their histories.

“We talked to the yungfellas about Pemulwuy, Kwementyaye Perkins, and they wouldn’t know anything about them” he said. “But then they’d be able to tell us when 2Pac was born, when he was shot, pretty much everything about different rappers.”

Recognising that hip-hop is a culture that originated from an oppressed people, Wright said that they used it “as a tool and avenue to reach younger people and promote our culture, our Aboriginality.”

Speakers emphasised that despite First Nations people’s work and successes, justice can’t be achieved without reciprocity from settlers.

Associate Professor Megan Williams, a Wiradjuri woman and Research Lead and Assistant Director of the National Centre for Cultural Competence, has been doing over 25 years of research on First Nations people’s health and wellbeing in prisons.

Pointing to works such as the Uluru Statement from the Heart, she noted hundreds of stories of success of First Nations people taking the lead: “We’ve got so many solutions identified… from an Aboriginal perspective, we know how to do all of that research.”

“Why then do we have prison rates doubling and so much worse in the last 20 years?” she asked audiences. “Something doesn’t add up.”

In one of the most poignant moments of the panel, Aunty Norma asked: “What is it that the rest of Australia is so afraid of? We’re 3% of the population, they’ve taken most of our land,” to which Wright responded: “Whenever we’re around…and we’re living and breathing, we’re reminding [settlers] of the genocide they didn’t finish.”

On that point, the panel concluded with panellists being asked whether they thought that Blak lives would improve in their lifetime. While they couldn’t quite say yes, they said that they had hope, with Williams stating: “It’s contingent on…the 97% being better.”

You can support Yabun Festival by liking their Facebook page and donating to Gadigal Information Service here.