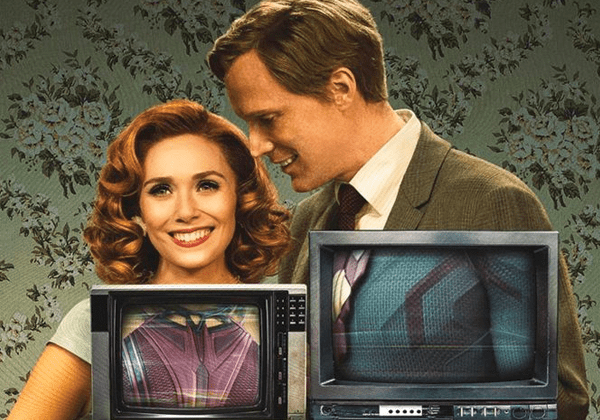

WandaVision is an absolute hoot. But while it’s a hoot, it also symbolises a shift in Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) programming; away from the traditional feature film format, but pre-eminently away from the safety of the MCU formula. While most Marvel movies (and most big-budget blockbusters in general) sell themselves on grand action–set pieces and fast pace, moment to moment combat, WandaVision doesn’t. In a departure from the MCU of winter’s past, WandaVision presents itself as a psychological thriller – exploring character and aesthetic more than anything else. In the heaving behemoth that is the Marvel machine, this is innovation.

This innovation isn’t just a creative decision made in isolation, though. Marvel, as a studio, and the creative risk it’s willing to bear, has always been directly linked to its stages of development. Phase 2, a period of consolidation for Marvel, has many of the most formulaic films of the MCU — namely Thor: The Dark World (2013) and Age of Ultron (2015) being the top offenders. Phase 3, on the other hand, has some of its most vibrant entries. According to traditional economic and cultural theory, monopoly and market homogeneity breed stagnation. Yet the more Marvel consolidates its dominance over mainstream entertainment, the more risks it’s willing to take. WandaVision is a product of this.

Starring two less than central characters, streaming on Disney+, and with a main hook that’s less appealing to a casual audience, WandaVision could only have happened in Marvel’s present stage. I like to call it their post-consolidation secure growth stage. Right now, Marvel Studios is too big to fail. Literally. I cannot envisage Marvel content being anything less than significant. That might seem naive of me, but I think they’ve proven themselves. If Age of Ultron (2015) and Thor: The Dark World (2013) didn’t kill the franchise, nothing will. Monopoly has always been an incentive for innovation in a market economy and that same rule applies to the MCU. Intellectual property laws, a form of legal monopoly, have long been considered necessary for private corporations to invest in research and development. Conventional wisdom is that innovation isn’t a financially sound decision without the legal assurance of exclusive profit. Without innovation several life saving, world changing, and genre defining products and services might never exist. Sounds pretty good, right? Now, the development of a new vaccine or the aeroplane’s invention aren’t exactly on par with a Disney+ content drop. But the primary principle remains the same: risk is encouraged when security is assured. Just as intellectual property laws protect the products of research and development (and the Disney corporation, for that matter), so does the market dominance of the MCU defend it from the consequences of a programming risk.

WandaVision follows Endgame’s record-breaking box office earnings and Disney’s acquisition of Fox. Both signifiers of the corporation’s absolute market domination. And that dominance Is manifesting itself in other media as well. Black Panther, Captain Marvel, and the Eternals all represent firsts for representation in the MCU. They also all appear in later phases of the franchise or, in the case of the Eternals, have yet to be released. All of this is innovation in the shallowest terms, but for a franchise that has often been criticised for stagnation, things are changing for the better.

As much as I’d love to finish off by saying that media diversity is a small price to pay for the absolute romp that is WandaVision, I can’t. As much as a monopoly has giveth, it has taketh some too. Almost 40% of the US box office figures went to Disney productions in 2019. On principle alone that’s something that isn’t exactly tolerable. As a member of any fandom, it’s important to remember that the characters we watch and the shows we consume aren’t just art in isolation. Disney’s acquisition of Fox was adored by the Marvel masses (myself included). The opportunity for the Fantastic Four and X-Men to enter the MCU was simply too tantalising a prospect to ignore. But these aren’t just characters — they’re representative of an ever narrowing media ecosystem. So while it’s fun to contemplate whether monopoly might actually encourage innovation, just remember that Quicksilver isn’t the only thing the Disney corporation owns now.