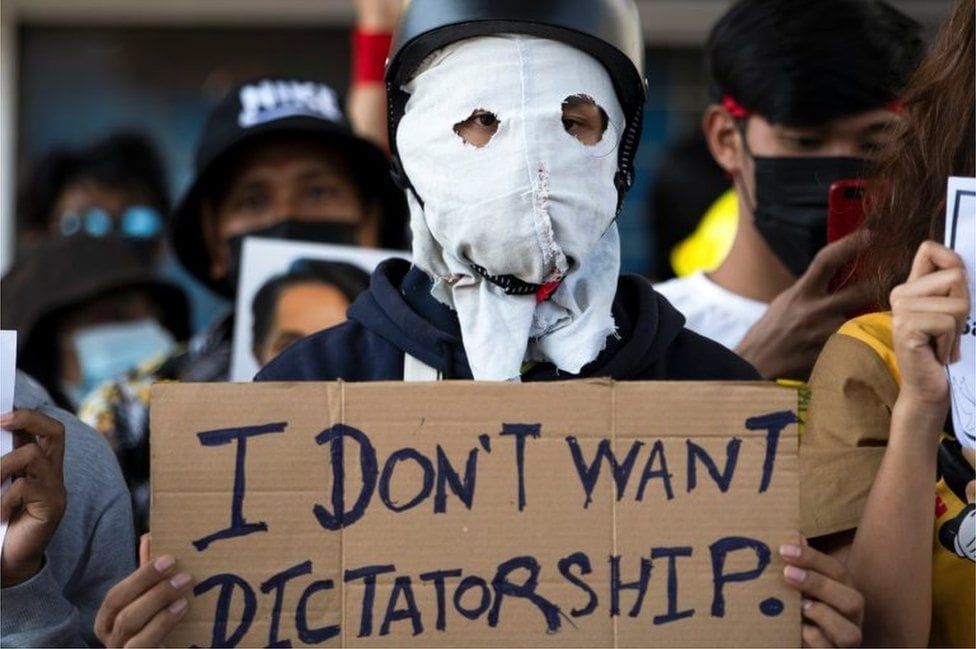

In the wake of the worsening military coup in Myanmar, which left a university student dead during protests, the Australian government remains unwilling to fully sever military funding with the Tatmadaw. Instead, some human rights critics argue, Australia has further legitimised the military leadership by engaging in direct contact with Vice-Senior General Soe Win.

On February 1st, during the first sitting of the newly elected parliament, the Myanmar military, the Tatmadaw, accused the National League for Democracy political movement of election fraud following the November elections. Despite constitutionally having 25% of seats in the parliament reserved for the military, Tatmadaw leaders categorised the elections as having been unfairly won. As such, the state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, and other leaders have been deposed, placed in detention, and the country has been declared a state of emergency.

The Australian government’s response, or lack thereof, is jarring in the context of the global outcry against the coup. The Morrison government has been heavily criticised by Labor, the Greens Party and Human Rights Watch Australia for a lack of proactivity in responding to the military coup. Penny Wong of the Labour Party has called on the government to send a ‘clear signal to Myanmar’s military leaders’ that the deposition of a democratically elected government will not be tolerated.Historically, the Australian government has sanctioned six members of Tatmadaw, but no new sanctions have been announced since the coup. As such, Human Rights Watch has highlighted in their criticism that Australia’s response to previous human rights issues, such as in Thailand in 2014 led to immediate severing of ties. Internationally, the US has announced sanctions against coup leaders, blocking access to 1 billion USD held in America.

The Australian government has long had military ties with the Tatmadaw. It has been one of the few countries to continue to cooperate with their armed forces since the ethnic cleansing and genocidal actions against Rohingya Muslims in 2017, having spent around 1.5 million dollars in funding in the last five years.

This funding was provided under the rationale of aiding to smooth the transition to democracy and further educating officers. Australia aimed to be an example and highlight the importance of international humanitarian law, but this influence has not proffered the desired effects. The military in Myanmar continues to reject democratic elections, and a coup has been staged through the utilisation of force to overthrow the first freely elected government since 1965. Thus, the question stands, should Australia maintain these ties?

Although on the surface, withdrawing support and following international suit may seem appealing, this option is not as simple as it may appear. Such a withdrawal, whilst fundamentally rejecting the actions of Tatmadaw, may further drive them to form closer alliances with China. This, according to the Australian government, is the biggest risk in changing tact. China and Russia have blocked a UNSC statement to condemn the military coup, and the strategic position China holds, sharing a border with the nation, makes it likely that the Tatmadaw will return to China as a key partner in trade and policy.

Surely, the current game plan, to ‘stop, pause, see what is going on, and then…make further decisions’, according to Trade Minister Dan Tehan, is not enough to prevent considerable damage to a new democracy. Surely, any ‘business as usual’ becomes untenable when it fails to avoid violating constitutional law and constrain the rights of citizens.

As tension heightens and pressure from the international community continues to mount, Australia’s government has attempted to secure the release of detained Professor Sean Turnell, an Australian academic working as an advisor to Aung San Suu Kyi. In a recent phone call with Soe Win, Vice-Admiral Johnston urged the Myanmar military to refrain from violence. This call again emphasises the precarious position that Australia is navigating. On the one hand, by using the Australian military, Aaron Connelly suggests that Australia has avoided legitimising the Tatmadaw as government. Nonetheless, human rights critics, such as the Australian Centre of International Justice suggests that this directly undermines the coordinated global effort against the Myanmar military.

The growing complexity of the coup only increases interest in Australia’s stake in the conflict, and brings attention to the decision that Australia ultimately has to make. Will Australia maintain a relationship with a military that has long prioritised power over the citizens they govern? Or by refusing to entertain normalise the coup, will Australia side with nations such as the US, Canada and the UK in an attempt to prevent further atrocity.