In the world of reality TV, the Bachelor franchise occupies a particular space of unreality. The show’s premise – approximately 30 suitors getting chucked into a mansion and vying for the attention of one man or woman – feels oddly antiquated, like a medieval courtship. It sometimes smacks the viewer with its absurd earnestness; more than other shows, The Bachelor and The Bachelorette ask you to suspend disbelief for the idea that two strangers who have spent minimal time alone can, through the power of love and incessant product placement, commit to an enduring relationship.

Perhaps it’s this wretched commitment to fairytale-like love stories that explains why fans of the US franchise have been stunned by its recent racism scandal, which centres around Rachael Kirkconnell, the winner of the latest season, attending an Antebellum-themed party in 2018. (The word “Antebellum” is sometimes used when glorifying the pre-Civil War Old South, while ignoring its reliance on slavery and plantations.)

The franchise became further engulfed when host Chris Harrison, on a podcast with the first Black Bachelorette Rachel Lindsay, defended Kirkconnell’s actions, saying there was a “big difference” between whether Kirkconnell attended the party in 2018 compared to 2021. In mere weeks, the other contestants released a statement denouncing Kirkconnell, Harrison temporarily stepped aside as host, and Matt James, this season’s Bachelor, dumped Kirkconnell.

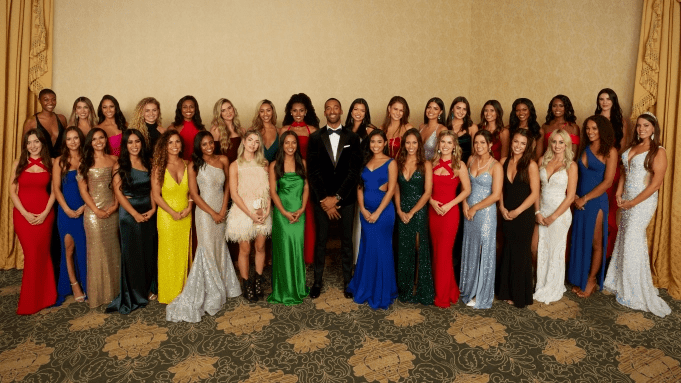

All of this happened after James was touted as the first Black Bachelor, following calls for diversity after June’s Black Lives Matter protests. It’s telling, but not surprising, how it was James’ season which exposed the franchise’s deep problem with race.

The Bachelor and The Bachelorette are interesting because they venerate the lead as a perfect romantic ideal. They’re presented simultaneously as a Greek god/goddess-like sex symbol, and a demure partner who just wants to settle down with someone who’s “here for the right reasons”. More specifically, the show is designed, mostly, to protect the lead’s interests; the events of the season, including drama between contestants, are framed as part of our hero’s “journey”.

And so, when Kirkconnell’s racist past directly conflicted with James’ identity as a Black man, the show could no longer choose to ignore its current and historical whiteness. Sure, viewing figures for Lindsay’s season dropped 10% on the year before – and Lindsay’s involvement with the franchise after her season quickly morphed into her becoming “the show’s Black Friend, proof that The Bachelor simply couldn’t be racist” – but Lindsay is still married to her winner, so the narrative remains intact.

On home soil, the Bachelor franchise in Australia has been consistently criticised for casting predominantly white men and women (and coincidentally sending people of colour home in the early weeks), while only choosing two POC as leads out of sixteen in the franchise’s history. A Network Ten executive blamed this lack of representation on “certain cultural groups” not wanting to be on the show.

But apart from this questionable generalisation which recuses production of responsibility, POC have simply never seen how they could stand a chance. The Bachelor franchise is made through a “white gaze” – the default assumption that the viewer is white – evidenced by POC contestants being rendered invisible (see Niranga, a Sri Lankan man, whose 2020 Bachelor in Paradise storyline was how he was constantly friendzoned), pitted against each other (see Sogand and Danush’s rivalry in 2019 because they were both Persian) or exoticised (see Tahitian contestant Elora in 2017 was characterised as a mysterious island dancer). It’s important to see POC be both the object of genuine affection and capable of giving that affection, on a nationwide platform, and to be protected from harm when they are vulnerable, which is where viewers argue The Bachelor failed James.

There are limits to how effectively representation within the fictitious environment of a TV show can change the world outside of it (James received racist abuse from fans after dumping Kirkconnell). Recognising this, the Bachelor Diversity Campaign, after successfully pushing for a Black Bachelor, is advocating for more POC producers and mental health support for contestants. Nevertheless, there is cause for cautious optimism; the latest US Bachelorette aired a widely-praised conversation about Black Lives Matter with Tayshia Adams, who is half-Black, and Ivan, a Black contestant and Tayshia’s runner-up. And the newest NZ Bachelor, Moses Mackay, demanded a racially and size-diverse cast before signing on. It’s by following their leads, and telling POC stories authentically, that The Bachelor can have a chance of embracing the present.